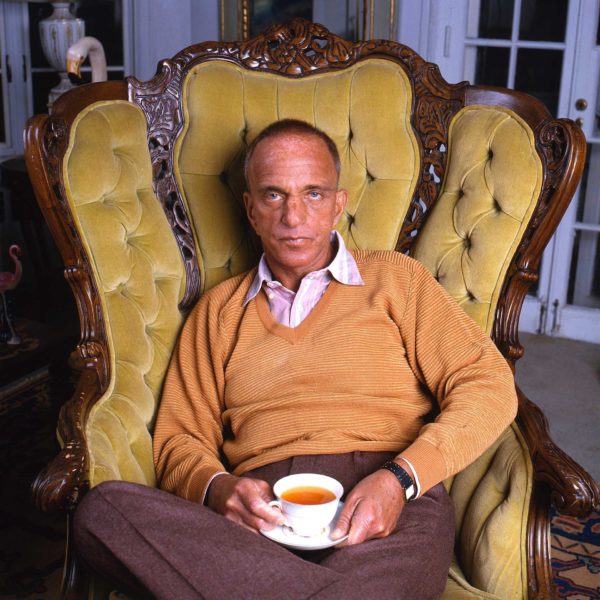

“When Trump won, Roy Cohn went from a footnote in history to become the modern Machiavelli who helped create a President for the United States,” says journalist and documentary filmmaker Matt Tyrnauer. In Where’s My Roy Cohn?, Tyrnauer tells the story of one of the most villainous and influential men of the 20th century, connecting the dots between the past and the present. A remarkably intelligent but ruthless lawyer (graduating from Columbia Law School at the unprecedented age of 20, he had to wait a year before being old enough to pass the bar), Cohn played a catalytic behind-the-scenes role in a series of events that marked American history.

At just the age of 23, Cohn was appointed chief counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Communist-hunting subcommittee. He subsequently secretly communicated with a judge to send Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the electric chair, participated in J. Edgar Hoover’s lavender scare, and defended elite families and the biggest mafiosi of New York City. Cohn also molded the political career of his mentee, a young Queens real estate developer whom he defended in a civil rights infringement case. That man was none other than Donald Trump.

Tyrnauer dives deep into the portrait of a profoundly contradictory persona. A “self-hating Jew,” a closeted homophobe, the bridge between priviledged elite circles and illegality. Tyrnauer attempts to understand the causes of Cohn’s amorality and reveals the utter hypocrisy that followed him his whole life. Cohn died of AIDS in 1986—refusing to admit his homosexualty and insisting that he was suffering from liver cancer until the very end—but as Where’s My Roy Cohn? shows us, his mark still runs deep today.

Sony Pictures Classics’ Where’s My Roy Cohn? premiered at Sundance in 2019 and is currently in theaters in New York and Los Angeles.

What drew you to Roy Cohn?

I was making Studio 54 in 2016, and Roy Cohn is a big part of that film because he was the lawyer of Studio 54. All the time I was cutting that film, I kept thinking that he was such an extraordinary character in this archival footage. He’s so interesting and so dark and horrible in every way, but there’s never been a documentary about him. However, I thought Hillary Clinton was going to win, and the real reason for doing a documentary about Roy Cohn right now is that he created Donald Trump. So when the election went the wrong way, I decided to make the movie immediately because I think, in order to understand Trump, you have to look at Roy Cohn.

The title refers to the now very famous words uttered by Trump after he believed he was betrayed by his then-attorney general, Jeff Sessions. What did you want to convey by using this as the title of your film?

When in 2017 then attorney general, Jeff Sessions, wouldn’t un-recuse himself from the Mueller investigation, Trump blurted out, according to The New York Times, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?” which is to say, “Where’s my mafia lawyer?” He was the creation of Cohn and he was the client of Cohn, and Cohn conditioned him to think that rules or laws do not apply and that you could get away with anything if you were Roy Cohn—and, by extension, if you were Donald Trump. This dark symbiosis went on for many years in the 1970s and 1980s. After Cohn’s death, Trump—armed with his playbook—just continued proceeding in the same way, using all of these, “I’m Roy Cohn, I’m Donald Trump, normal rules don’t apply to me, I’m above the law” tactics.

That would have been repugnant, but not internationally dangerous or scary, if Trump had remained a reality TV joke. Now that he is the most powerful man in the world, it’s a very dangerous situation. The gravity of it needs to be understood by everyone, which is why I made the movie.

Cohn’s influence spans such a long period of time. He impacted so many political events in American history. Can you tell us about the research process?

I come from long-form journalism. I wrote for years as editor-at- large of Vanity Fair, with very deeply researched articles. I come from reporting and that magazine tradition. My process when starting a documentary is simpler. I do a deep-dive interview search. I have the help of research producers, and we get our hands on everything relevant and then read it all and start to figure out what’s known, what’s unknown, what’s interesting to us, [and] what additional reporting we might need to do. Then the story is shaped by that research.

And, of course, film is a visual medium. After that research period, the archival research starts, and we really work hard to get never-seen-before photos and videos. For this documentary, we got access to Cohn’s personal archive, with footage that was never seen before by the public. And then we start to put it all together. I’m really only interested in making films that are theatrical. I like things that are of scope and meticulously researched.

How did the research and the interviews you did help cast new light on some of these events? You seem to present the Army-McCarthy hearings in a different way.

Obviously, the Army-McCarthy hearings are one of the most frightening passages of our recent history. I think most people will know basically what the McCarthy hearings were, even if they don’t know much about McCarthy at this point or much about Roy Cohn, who was right there at the center of McCarthy’s reign of terror. In the Army-McCarthy hearing, he was not only at McCarthy’s side, he was the central figure. Gore Vidal referred to this as “The United States of Amnesia”, which I think is now more than ever a very powerful description.

So I wanted to unpack, as it were, the Army-McCarthy hearings, explain what they were, and show that Cohn at the age of the dawn of television was a malicious, narcissistic, lying force, power-mad, and put himself right at the center of this bizarre national psychodrama that a lot of people today don’t really understand. It was a responsibility to parse that.

And, to go even further, as this is after all a movie about Roy Cohn, to show that Army-McCarthy was in many ways the early reality TV moment. At the very beginning of the TV age, you have this very clever, evil, demagogue whisperer creating a media spectacle to exploit a particular moment in history. It’s all about him. It’s all motivated by a favor he tried to do for a guy that he probably had a crush on, trying to give him a promotion from private to general. Which is absurd. But when he didn’t get his way, he tried to blackmail the army with McCarthy and his usual smear tactics, claiming that they were communists. It was all nonsense. It resulted in this television show with Roy Cohn right in the middle of it, wasting everyone’s time and creating a moment very much like what we have to endure now with Trump and his shenanigans. It’s important to see that now, so that everyone knows that this has happened before and [that] it really all goes back to the same root cause, which is Roy Cohn.

Was it hard to make people who were close to him talk about Cohn’s actions and hypocrisy?

No, actually. I felt as if his cousins were sitting by the phone for the last forty years, waiting to denounce him. They really hated him. They are embarrassed by him. They are appalled. And now, with Trump, which they know very well is a creation of Cohn, they’re alarmed. And they are more alarmed than most people, because they know more than most people. So they were very happy to speak. One of the cousins, who had a vaguely more favourable opinion because he had been the recipient of a favor from Cohn, asked to be interviewed a second time because he wanted to say that he had done more reading and realized what a terrible person his cousin was.

Did you want to interview Trump for this documentary?

Yes, I asked three times. At the very end of the credits, there’s a card that says that Trump was asked multiple times to give an interview, and he never replied to any of these requests.

Your documentary doesn’t try to justify Cohn’s behavior, but there is an effort to understand why he acted the way he did. Did you try to find a balance in portraying such a controversial figure?

Journalistic reporting is supposed to be balanced. Balanced is not the responsibility of a documentary filmmaker. It’s the responsibility of a journalist in a newspaper or a TV or an internet context, absolutely. When you’re the director of a documentary film, you’re more expected and certainly licensed to have an opinion or a take. It’s just a different artform.

I’ve been the recipient of questions of various people who’ve seen the film expressing opinions on both sides of the spectrum. Some people have said to me that the film’s not hard enough on Cohn, while others have said, “Why were you so hard on him? It doesn’t seem like you were even attempting to be fair.”

In my style of journalism and filmmaking, I like to be somewhat observational and at least mildly oblique in my storytelling, assuming that the audience is capable of making their own conclusions when exposed to the information that I have organized in a fashion that I think is appropriate and also accessible to a general audience. I believe that making a documentary is for as wide an audience as possible, but obviously without dumbing things down. So part of my method is to present and exercise a certain amount of subtlety, and that’s what I’ve done here. I think Cohn’s actions and words are damning without my express opinion coming into the picture.

As the first-wave feminist Anne Roiphe put it in your documentary: “Roy was an evil produced by certain parts of the American culture. There always is the possibility of another person who cares not about our traditions or our laws or our protections, who can come in and wreck it for the weakest among us and the most vulnerable.” Can you comment on that quote? What are these “parts of American culture”?

What she’s referring to is the danger of a demagogue, the danger of a reckless, irresponsible, self-interested actor when they get power. Joseph McCarthy was such a person, but he was merely one of a hundred senators, he never came close to the presidency. Roy Cohn, as a mob attorney or power-broker in New York, was one of these people. Obviously, he was on McCarthy’s side, and in a way mentored by J. Edgar Hoover, yet another example of this dark, self-interested person. But again, Roy Cohn or Hoover were not President of the United States. They did their damage in more limited capacities.

Trump has captured the presidency and has it in a chokehold, and by extension has us and the whole world in a chokehold, because he’s only interested in himself, his own aggrandisement, and his own enrichment. That’s not the job of the President of the United States, to say the least. And when someone like that who behaves like a mobster, has that kind of power, with that kind of reach and the potential for global consequences, it’s a very dangerous thing.

There are a lot of documentaries recently that deal with important political figures, like Get Me Roger Stone or Raise Hell: The Life and Times of Molly Ivins. Are these documentaries attempts to understand how we got here, to explain the current political situation?

I think documentaries are very popular at the moment, and I hope that continues. One of the reasons that I think they are is that we’re all at the firehose of cable news and social media. Alas, people don’t read books as much as they should, and longform magazine journalism is really a dying form. People like visual media, and that’s undeniably powerful. Documentaries provide a couple hours—or more if it’s a limited series—of deeper consideration and more profound perspectives on important events. I think that the trend in political documentaries is a very healthy thing. The more audiences are exposed to these deep-dives about important aspects of our culture and our politics, the better off we are. If people keep on not reading books, I hope they keep watching documentaries and listening to podcasts.

This documentary revival can be seen both at the box office and on streaming platforms. Why is it important to see documentaries on the big screen?

Call me old fashioned, but I think movies are a medium best viewed in movie theaters. Not even entirely for the thrill of seeing something on the big screen, which is very important to see movies in the best way, at least if they’re movies that are visually striking and generally cinematic. But there’s something very important about the communal experience of the theater. There’s something very powerful about that whole experience, where you leave your home, maybe alone, maybe with other people; you converge at a central place, which is the theater; you sit in the dark for 90 minutes to 2 hours together; and then you walk out together, and as you’re leaving you contemplate or discuss or maybe go out for a drink or dinner and you have a communion. There’s a magic to that that we’re losing, because we’re all in our silos with social media and streaming.

Now, make no mistake, it’s wonderful for filmmakers to have so many platforms, and there’s nothing wrong with streaming media and watching a movie on a plane. You can get a lot out of it. But there’s an extra something to the theatrical experience. A kind of x-factor that I don’t think we’ll ever lose. I don’t think theatrical will ever go away at all. I think it will have a renaissance, if I had to predict. I make all my films to be theatrical, because I believe in it and because I don’t think we can reasonably dismiss the now century old practice of coming together in theaters to watch art. It’s one of life’s great pleasures, and I think it’s very healthy for society.

Share this post