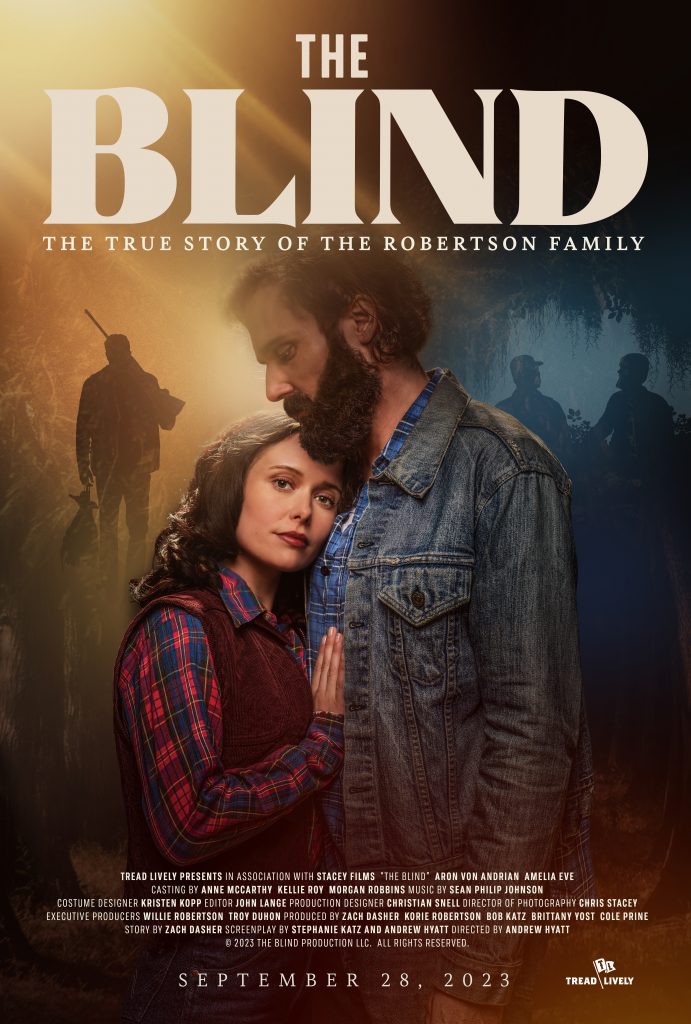

Long before hunting and outdoor recreation company Duck Commander became a media franchise and subject of the TV reality show sensation Duck Dynasty, patriarch Phil Robertson faced and overcame his personal demons. Opening exclusively in theaters on September 28th from Tread Lively, GND Media Group, and Fathom Events, The Blind divulges how the duck call inventor migrated toward faith and family, revealing never-before-told backstory behind the famous family’s past.

The big screen biopic marks Fathom Events foray into the world of specialty distribution with a longer and more robust theatrical run. Set in the backwoods swamps of 1960s Louisiana, The Blind is based on the life and romance of Phil and Kay, with a script ratified by the Robertsons. Boxoffice Pro spoke with director Andrew Hyatt about the redemptive story at the heart of the family’s foundation.

How did the Robertson’s origin story come to you?

A producer friend, Brittany Yost, had been on the project for a little bit. We hadn’t worked together, but we have mutual friends. I was brought in because [the producers] liked a film I had done called Paul, Apostle of Christ, for Sony Pictures and Affirm Films, a Jim Caviezel film with James Faulkner. I took a look at the script and what they were working with. At that time, it was a little more along the lines of the television show. A bit more anecdotal, a lot of humor. It was trying to capture the spirit of the show. I like really digging into a lot deeper themes and, for better or worse, I’m fascinated with redemption and death and all sorts of darker themes. So I actually felt like maybe it was not the right project for me. Then I randomly stumbled upon Phil Robertson telling the deep, dark secret background of where he’s been and what he’s been through. It just felt like, ‘Wow, that’s powerful stuff. That’s the movie.’

After hearing your pitch, how did the project take shape from there?

Stephanie Katz was the writer at the time. Thankfully, she was gracious enough to let me come in and start to do a director’s pass on it, formulating what are the big moments, the big scenes. We just got our hands dirty with the script, and again, helpful to have the family there to say, “That happened. That didn’t happen. Oh, actually, we’ve never told anybody, but this was the real thing that happened.” They were very gracious in allowing us to pry into some very personal [events]. That’s always hard, as any individual, for people to start looking at flaws and the difficult things in your life and say, “We want to bring this out to the world. We want people to know these things, because we think that will help people with addictions. We think it’ll help people that are looking for a purpose in life.” That’s gotta be hard, when somebody exposes the raw side of [your past]. We all have our things, don’t we? We all have our demons in our past. They were gracious enough to let us explore that. I think what we brought to light was, in trying to make a film that is universal, saying, “Hey, no matter where you’re at in life right now, there’s hope.” Whatever the subject matter is, that’s a universal theme that we all respond to in film.

Phil’s son Willie Robertson serves as a producer. What was that collaboration like, having direct insight from the family?

I think it was always a sense of, “How far should we push things?” That was a big thing. Because they have such a loyal audience, that did come into question a lot. What is this audience ready for? What are they ready to hear? What are they ready to get a smaller spoonful of? The way it worked was, I was digging into Phil’s revelations from his books and from the talks. We had plenty of sit downs [where I would ask questions like,] “When you kicked the family out of the house, in one of your darker moments, how did that feel? What was that like?” I’m a screenwriter and I can fabricate a lot, but if you’ve got the people that have lived through it right there–tell me what it felt like. What was it like? So it was that process. The uniqueness of it was then going to the rest of the family and saying, “Is this okay?” They were just so supportive, like, “Yep, it’s time to let people know that this really happened.”

I’ve done a few biopics before and it’s always difficult when your subject matter is still with us. It’s one thing to do a historical figure and say, “Well, we kind of know this, but we don’t know this,” but this was just very much like, “First of all, is it true? Did this happen? Second of all, are we okay with sharing this, because it’s so personal? Three, how much do we want to allow the audience access into some of this?” In terms of gratuity and language, in this kind of medium, you only need to see so much to get it. Do I need to see 30 scenes of that? Or is there one powerful moment where you say, “Whoa, I got it. I got it.” Everybody was so collaborative–from the producers, to [co-writer] Stephanie, to the family, that it was really–I can say honestly–a joy to work on.

That could be a fine line, given that the family has a dynasty and a business to think about.

To tell this particular part of Phil and Kay’s journey is just so counter cultural right now. We kind of beat the social media perfectionist drum, don’t we? Like, ‘Look at my life, look how beautiful it is’ on Instagram. Or on Twitter it’s, ‘I’m smarter than you. So my opinion matters more than you.’ God forbid anyone should dig into our lives these days and say there’s a lot of flaws here too. But what a beautiful thing, if we all just took a step back and said, “I am a flawed individual.” We all are, we all have our flaws. Maybe if we started to do that a little more, that human element of compassion could suddenly show itself. Where we say, “Hey, I’m actually willing to listen to you a little bit and understand where you’re coming from.” I guess it’s that old classic, “You never know until you walk in someone’s shoes,” but man, we’re not interested in that anymore, are we?

And what are stories on the screen if you only show the superficial side of things, like we often see on social media?

My favorite filmmaker is Andrei Tarkovskyi. His philosophy of what the medium of film is and can do is the concept of [holding] a mirror unto ourselves. Every story he told was meant to reflect on the audience, so that you’re watching the story, but it’s really [intended] to internally reflect on our own life. He had that belief that we’re all here for purpose. One of the main purposes is to better ourselves as human beings, but you can’t do that if you’re not willing to dig back into the junk and say, “Wow, I got a lot going on here that I need to face and look at.” I love that aspect of this film, because, although it’s Phil’s story, at the end of the day, it’s really for us to then absorb and say, “What do we each have going on that we could get better at.” That was one of the things that really excited me about telling the story. And what a beautiful medium to do it. Film gives you that ability. All stories do, but there’s something very powerful [in going] from the page to seeing it live. It just has power.

The Blind arrives at a time when Faith-focused films are finding a warm reception at the domestic box office. As a filmmaker, what is this moment like for you, returning to cinemas with this film?

It’s a great question. It’s sort of eye opening, isn’t it? All of a sudden [there have been a] string of faith centered films clearly targeting a certain audience in this country that maybe feels a little left behind or feels a little on the outskirts. While I can totally understand and see the success of that, I think another thing that drew me to this were these deeper themes. My hope is that it opens itself up to a wide audience. Forgiveness, redemption–these are things that we love in any story. My hope is that the faith elements, while they’re there, come across very organically, so that anybody from any walk of life can come and say, “Wow, that’s really cool. He got it together. Here’s how he did it.”

I’m just excited, first of all, that we get to go to theaters in the streaming day and age. It’s like going back to our childhood. I want to go to the cinema. I want to watch these things on the big screen and have a communal experience and then talk about it with other people. We’ve lost so much of that. I’m not making a statement, good or bad, on streaming, because I certainly do binge shows all the time, but as a filmmaker, what a gift and a joy [the big screen is]. On September 28th, I’m going to be able to sit in a dark theater with a community and watch the film. There’s no better feeling. It’s a great story with unbelievable performances. I’m so happy with this cast. It looks great. We use some Hawk Anamorphic Lenses, so I’m excited from just a film perspective too.

It seemed as though many of the films that came out of the pandemic featured heavy messages. Do you think audiences are responding to and looking for films with a hopeful message?

Speaking of a common experience, going through Covid was a dark time for a lot of people and they’re still coming out of it. Things are really rough and tough right now. I was blown away by the fact that so many films just had this dark [message]. The last thing you want to do is sit down and go through those experiences again. To your point, you just want a little bit of light at the end of the tunnel. For the films that seem to be doing really well right now, you leave the theater feeling some hope. I think that those are the kind of films that everybody’s just desperate for right now. TV is the same thing, isn’t it? You watch so many shows that have this narcissistic [view]. There’s no hope, everybody’s kind of miserable and we’re all stuck here together. What if we started to look at each other differently?

Fathom Events is rolling out the red carpet for The Blind with a longer theatrical run as a part of its specialty distribution model.

That’ll be unique, because I think they do such a great job of the one-night-only events. These days, I think you have to be so unique in your approach of how to get people out of their chairs and off their couches to go see a movie. Fathom does such a good job getting people out for one night events, which seems impossible to me, because people are busy and they’ve got other things going on. So I’m excited that they have a little run time to say, “come out opening weekend.”

Do you have a favorite moviegoing memory?

We weren’t a filmgoing family, so it wasn’t as prominent in my upbringing. I remember watching the Elizabeth Taylor Ivanhoe over and over again; acting out the scenes by myself. In fact, I still have a couple of copies. I give them out to people, because I love it so much. Nobody seems to know about that film. I remember my mom took me to Jurassic Park. I think that was the first big movie that I saw–probably a little too early–because it’s still, psychologically, all over the place in there. I just remember being terrified, but blown away by everything about it. She also took me to The Blair Witch Project, which had its own psychological [impact]. You just have these memories. Why is that one still around? Why am I still thinking about that when so many memories fade away?

Would you like to make a film on the scale of Ivanhoe?

It’d be a blast. We told my oldest daughter once she finishes [reading] The Lord of the Rings trilogy, that she could watch the movies. The last week and a half we’ve been bingeing Peter Jackson’s extended version of The Lord of the Rings. If I could do that? Oh, that’d be it. I think I’d retire. Do that. Retire. I did it. You know?

Share this post