Macedonian-born and Australian-raised writer/director Goran Stolevski began creating films in his high school days, making some 25 shorts over a 16-year period. His work has been screened at over 200 festivals worldwide, including the Sundance Film Festival, where his film Would You Look at Her won Best International Short in 2018. Last year, Sundance premiered his feature film debut, You Won’t Be Alone, a supernatural drama about a witch in 19th century Macedonia. Focus Features pre-acquired worldwide distribution rights for the film and now re-teams with the filmmaker on his second feature, Of an Age.

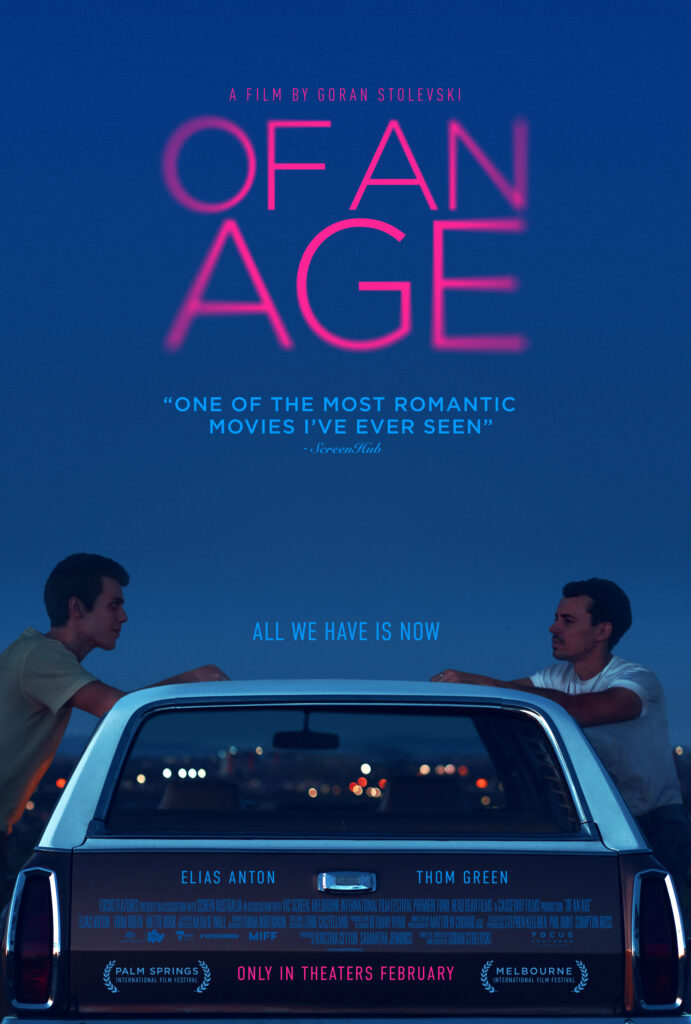

Set in the final summer of the ’90s, Of an Age sees romance spark between a seventeen-year-old Serbian ballroom dancer and his best friend’s older brother. In advance of the film’s February 17th release, writer/director Stolevski spoke with Boxoffice Pro about his CinefestOZ prizewinner and the divine jolt of making one-on-one connections in the cinema.

What has the process of transitioning from shorts to features been like for you?

You can deal with bigger feelings and tell bigger stories. Most of my short films were DIY things made with literally no money—trying to borrow a camera from a film school, or a computer from the council to edit it on, and find friends who aren’t actually actors that might be willing to be on camera. You go, ‘How do I shape these ingredients into something that could be interesting to someone else and transport them somewhere?’ There are limitations, inevitably, to that, which actually I think is quite good when you’re learning how to make films. It’s a really useful skill for later on. Now, I get to work with very good actors and very good crews. I no longer have to do the first assistant directing and catering. Which is so relaxing. It’s a bigger canvas for stories.

Your first and second features, on the surface, seem so different from one another. What draws you to relationship dramas and to the stories that you’re telling?

I’m always looking for a web of relationships that sets the heart pumping. I think usually my stories are about outsiders trying to blend in to survive. Processing their own feelings, knowing that you can’t always talk to someone else about them and expect them to understand you, if ever. Looking at people in the context of the kind of loneliness that puts you in, but within that context, trying to find the moments that are beautiful and make everything else worth it. Focusing on things that connect with people who are very different from me, so that other people can watch this movie and still take away something from it.

What was the genesis of this project?

I was reading a short story about an Irish schoolboy who falls in love with a cadaver. At one point, halfway through the story, he goes to his first-ever party. He steps into this room and when I was reading the story, I could not get to the next sentence or the next paragraph, because all these memories started flooding back from the one party I ever went to in high school—not in pursuit of a cadaver—but trying to see how normal kids engage and interact with one another. The memory was so vivid. Not in terms of events that happened there, just the context, the feeling of who I was then. The feeling that was [my] day-to-day life and mindset. It’s a time in my life I never really think about. It wasn’t really traumatic in a traditional sense. It was extremely and deeply dull. I felt very alienated from where I lived, partly from being a migrant. A kind of an emotional dislocation that had nothing to do with my circumstances; it was purely internal.

It’s a time of my life I was very absent from, and then suddenly I was experiencing this intense memory of that feeling. In the context of who I became later and who I am now, I was looking to explore that feeling. In that time and place, with those kinds of limitations. Specifically in 1999 before mobile phones and technology made it easier to connect and find people who are like you. Living in that feeling and figuring out how to find love and romance in this context wasn’t always easy. But [rather than] concentrate on the obstacles, concentrating on the things that were poignant and [are] not really preserved in stories.

Focus Features has been inviting moviegoers to spend a romantic evening at the movies this weekend. Why do you feel it’s important for audiences to see diverse love stories in theaters with an audience?

Firstly, it’s important for those diverse stories to also be good. Ideally, to be able to emotionally connect with all kinds of people, without diluting the queerness. I want any person, especially a queer person I write, to have the right to be as unlikable and destructive as Walter White is in “Breaking Bad”. I don’t know why I don’t get to be the antihero. I want to have a very complete and undiluted version [of my characters]. I also don’t want to announce the diversity; I think it needs to be presented in an organic way. This film is actually a very specific case for me, in the sense that, I think there is a special kind of loneliness if you’re a queer person, especially before technology made it easier. When you couldn’t find any other queer people. It’s a specific type of isolation. When you find someone you have something in common with, it’s a much more electric relationship in a sense. I think there’s a positive aspect to that. I think it’s incredibly fucking sexy that you’re the only two people in a room that have this electric connection and know something about each other.

How have audiences responded to the film?

I really love that at the end of screenings across festivals, the people who came to me crying, going, ‘How did you know my story?’, were straight women. In their 20s, 30s, 50s, and 70s. So gays don’t own loneliness. I think we have a special insight into it, but that’s a whole other thing. It’s presented here in a very specific, queer way, but I also think other people can connect to it. I could be in a mining town talking to a pensioner; a woman who is learning things about her own feelings towards the world. I don’t know how much change can happen from a movie, but I think if it can, that’s the way. That’s what I aim for. Going to the cinema, to this day, you’re transported in a particular way that you can’t be while you’re washing dishes with Netflix on in the background.

AT THE MOVIES

Do you have a favorite moviegoing memory?

I’m going to sound like such a film nerd. Orson Welles was, to me, what Jesus is to Christians. For many years. Still is, really. The ability to go to an Art Deco theater in 2014 and watch a double bill of Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons projected on film. The theater was almost empty, but I didn’t give a shit. To me, movies are a one-on-one connection; I’m connected to Orson and no one else. That was one of many low points in my life professionally, where I was nothing and no one. None of my films were selling, but I really liked that feeling of, ‘Look at what’s already been created’. It makes you want to keep trying, but even if it doesn’t work, at least this already exists. What a gift.

I’d been a film nerd for twenty years by that point, and reliving that feeling of what movies were. The first time I watched Citizen Kane, it was imported from a library and I had it probably a week. Our VCR got stolen that week and we couldn’t replace it. I had to go to my cousin’s house three buses away and beg them, ‘Can I please just watch this one movie?’ I’m sitting on the floor watching a TV, which isn’t really considered a cinematic experience, but I don’t remember anything happening around me. I was only 13 or 14 at the time, but I was transported. I never thought I would see it in the cinema and then I did. That’s a cinematic memory that I will cherish.

Share this post