How did you get involved in this project and what did George Foreman mean to you personally growing up?

My knowledge of George was through boxing, right off the bat, because my father was a huge fan. Then, obviously, the grill later on. But the biggest thing, for me, I remember in 1987 when he made his comeback. I was there, I remember seeing him fight Steve Zouski, who I believe is actually from my same hometown: Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Zouski was one of those guys that fought Tyson, he fought everybody. He just didn’t win! [Laughs.]

The whole thing about that is I didn’t think George would keep winning. He kept winning, like 18-0, 19-0. He kept saying he wanted to fight Mike Tyson. I was just laughing and falling in love with this new George Foreman. That was completely different from the guy who knocked Joe Frazier out six times and never smiled in that whole fight.

So I was just blown away by this whole journey. I just felt that it was a terrific story, I couldn’t believe it was never told. And it’s all true, you can’t make any of this up.

As I was watching the film, it slowly dawned on me that you were recreating—line by line, word for word—some of those iconic broadcasts of Foreman’s classic fights. Howard Cosell, Steve Farhood, Jim Lampley—voices that are instantly recognizable to fight fans in the United States. How important was it for you to lend that level of historical authenticity to the film?

I think that’s the key. Because as you just said, if you go to YouTube, if you go to ESPN, they broadcast these fights. Everybody’s seen them. So how do I make people feel that they’re actually there? A lot of these fights were outside stadiums: Zaire, Puerto Rico, sometimes they were at the Hilton, Caesar’s. That atmosphere, the smoke, the crowd packed in. The way they have these big floodlights coming in and creating these flairs. All those things, people don’t see today. How could we stand out from other boxing movies?

I just felt we had to recreate these fights to a T. We had to hit: real fights, real punches. The Ali / Zaire fight, Ali hit that three-punch combination. We did that 45 times. So you’re just trying to have a sense of being the best you can to create these, because they are on YouTube and people are able to judge that. I really want us to be as true as possible.

You also have the challenge that there are other cinematic references for some of these fights. You think of Michael Mann’s Ali, where that fight is recreated in its own version. You also have the documentary When We Were Kings. How did you have an original vision to bring to the screen, that wasn’t too distracted by other references that were floating out there?

I think the key for me was, I knew these fights. I was a fan: a fan of those filmmakers, a fan of those boxing movies. A lot of that was, for me when I started doing this film, I had to let myself go. Wasn’t able to watch any of that. I stayed away, worked on my instincts in terms of my research with George, my research of watching the fights, and keeping it in George’s perspective.

I knew that right away, when I talked to Foreman and he said, “You know what? I only saw Ali one time, in Zaire.” I said, “You didn’t have a conference?” “We didn’t have a conference.” So those movies that had a conference? I knew right away, I had to stick to my point of view in how he saw things, because that was George Foreman’s story.

So that event where he sees Ali at the Intercontinental Hotel, in the lobby, that’s a real true incident. A lot of people don’t know, they haven’t been told. So that’s what I really did as a filmmaker, is really stick to that.

Like every other fighter of his era, so much of George Foreman’s early persona was overshadowed by the immensity of Muhammad Ali. When he resurfaced in the late 80s for the second half of his career, he was no longer the destroyer of men who turned Joe Frazier into a pile of dust, but this gentle giant figure who sold grills on TV. Can you talk about that transformation, and how your lead actor, Khris Davis, embodied that role?

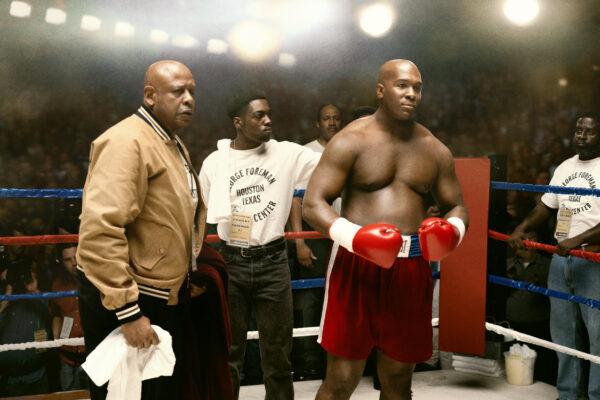

We had a really good process. A lot of that, early on for me, was creating a little bit of a development program over a year to really break down the choreography, the fights, learning how to fight, and in the behavior. What was the behavior pattern of George in the ‘70s is completely different: how he walks, how he talks. He’s a completely different guy. That goes with our self-awareness that’s in our plot, of a transformation of a guy who wants to better himself. That was very early on.

The humor and the love and the likability really doesn’t just come out of nowhere. It’s built in, it’s there. It’s there as a kid. We sent little small hints of it. But what happens is, your atmosphere, your climate around you suppresses that. So George was angry, but he was still likable. There’s something about us, even as angry men, we just lean in. Because it was already there. When that transformation happened, you were able to bring that out.

So we talked about that, me and Khris, for a very long time. Really worked on his behaviors. What we decided was, let’s just hit it one block at a time. So the first block is from 1960 to, at that point, ‘77. Then we stop. Then in six weeks, we had to gain the weight. He picked that up and did start doing the work for the second George, where you see the different hair, everything sort of changes.

So that was the plan early on, but you need an actor who’s going to be dedicated to that, who can stay on that. Khris is from Philadelphia and lives in New York City. George lives in Houston and has that dialect that he has. How do you get that dialect, and how that dialect changed was very important to us.

There are so many peaks and valleys in the life of George Foreman, even in his career. We talk about an early peak, gold medal winner in the 1968 Olympics, a very important Olympics for many social reasons. Then you go into the Frazier fight. And then the amazing upset loss in the Ali fight, the “Rumble in the Jungle.” And in the comeback, the highs of moments like the Moorer fight and the lows of losing against Holyfield. How did you go about in balancing those peaks and valleys in the film?

What it was, when I talked to George, the first thing he was saying was: “I was not in a good place when I went down in Zaire.” His marriage was falling apart at that point. I knew at that point he was doing a lot of going to court, he was dealing with a lot of things going down there. Can you imagine? You’re going down there, your whole life is to be the champion. You are the champion. Your name is first: “Foreman vs. Ali.” Then you go to another country before you get down there. Everybody is rooting against you.

To hear those things, keep in mind, at that time he was only 25 years old. So as a young kid, , getting all that information, hearing all this. “I’m the champion, but you’re rooting for that guy? I went to the job corps. I went to work my way and held the flag.” So all that pressure. That pressure was: “Hey, I’m getting him out early and getting him out fast.” That’s sort of what happened.

I don’t think either of those men knew or were ready for the heat, even though they’d been down there a couple times. Trying to get yourself acclimated to the heat in Zaire played a factor for Ali to stop dancing, and it played a big factor for Foreman getting fatigued, with eight rounds of doing the same thing in each round.

So those are the things, trying to get in the frame of mind and let the audience experience that. I don’t know if you saw in the film, he’s looking out and he’s bending down, he looks over his shoulder, he sees Ali there. Then he gets up and you see a POV of the whole crowd saying: Ali Bomaye.” How does that affect someone? So I wanted the audience to feel that.

What it does for an audience, especially a young audience who never experienced that suspense, they’re on the edge of their seat. A whole country against you. How does that make you feel? That’s what I wanted to get the audience to experience.

There are so many quiet, intimate moments in the movie as well. How closely involved was George Foreman himself in giving you insights into these moments?

I’m glad, thank you for catching that. Can you imagine? He’s looking back and there’s Ali with a connection. Later on, that connection is going to be him.

One of the things, the truth of that is the sense of looking for approval. “If I just get to the Olympics, I’ll get their approval. If I just get to the championship, I’ll be like Joe Frazier.” He says it: “I want to be just like Joe. I want to have those things, right there.” You look for all these material things. What I love about the journey is, later on, he was able to find the approval within himself.

It made me connect early on, when Doc Broadus [played by Forest Whitaker] says: “It’s right here.” [Points to his temple.] So later on, he fought Michael Moorer in a different way. The Michael Moorer fight was so different from the Ali fight. That knockout came out of nowhere. I was watching the fight, I’m ready for something to happen, and it just happens! [Laughs.] That’s someone who’s thinking strategically, who’s thinking maturely as a boxer, doing the right thing.

But those are certain layers, as a filmmaker, that I feel: do your homework properly, you build the scene, the throughline, the connection, the tissues. Like my wife always tells me, I like to do detective work. That’s just who I am. I always felt like that was the second thing I wanted to do in life, was be a detective. Part of being a filmmaker is doing the detective small things, linking this to that.

Being a puncher who’s in second, you want to knock somebody out in two or three rounds. Then when he fights Zouski, it’s not about hurting anymore. Those are things that I feel we should properly set up.

How did you go about depicting the religious aspect of George Foreman’s life, a man who found God later in life?

That’s something, as a viewer, for myself as a spiritual person growing up in church, but as a filmmaker, sometimes you watch a movie and you feel like you’re being preached to. You know what I mean? You feel like you want to have a spiritual awakening organically, just like George felt it was an organic process. You want to do it in a delicate way.

So it’s got to be delicate with a film like this, because boxing films traditionally don’t take that turn, where all of a sudden there’s a religious spiritual awakening and he stops boxing. There’s a new person. But then you see that he has nowhere else to go, after the loss of everything, to go back to the ring. So the spiritual awakening is: “I can’t do it the way I used to do it.”

Which is in our own life. If we’re going to make changes, you can’t do stuff you did back in the past or do the same. First, you’ve got to be able to acknowledge it, you’ve got to be able to have a verbal acknowledgement and an ownership to it, be able to acknowledge who you are so that change can be. That’s what he did.

Even the small moment when he’s talking to Mary Joan, his second wife [played by Jasmine Mathews], he says: “Hey, things are different. I’m a different person now.” She can read right through him. Those are the things that I think are human experiences an audience can be able to relate to.

There are several other big names in boxing who found their faith during their careers, and as fight fans we’ve been able to see how that changed the way they performed in the ring. Names like Muhammad Ali, Evander Holyfield, Manny Pacquiao—these are all boxers whose fighting style changed slightly after they found their faith. We see George Foreman going through that in the ring in this film, how did you go about in addressing that side of his identity?

I always felt like the scene, there’s a moment where he finally gets some money back. He could have stopped boxing at that point, but there’s a higher power that said he’s going to be bigger than he ever was. And he kept fighting, in a very patient way. He could have walked away from it. That’s a difference from the guy who would buy all those cars, in the first part of the movie. He tells his mom: “Wait until you see my garage. I got five more of these, five more cars.” To a guy later on who’s like: “Money doesn’t mean anything. I’ve got to do it for another reason, a higher spirit.”

Those are great characters, but then George in his real human life is the real deal. He’s the real person. That makes it very exciting, that you have such highs and lows, such excitement, so much humor. The guy had to lose weight to come back the way he did, being that large when he fought Steve Zouski and being ready to fight Michael Moorer. Those things, things can happen if you just believe. You just keep pushing. That’s the inspirational side of the story.

Share this post