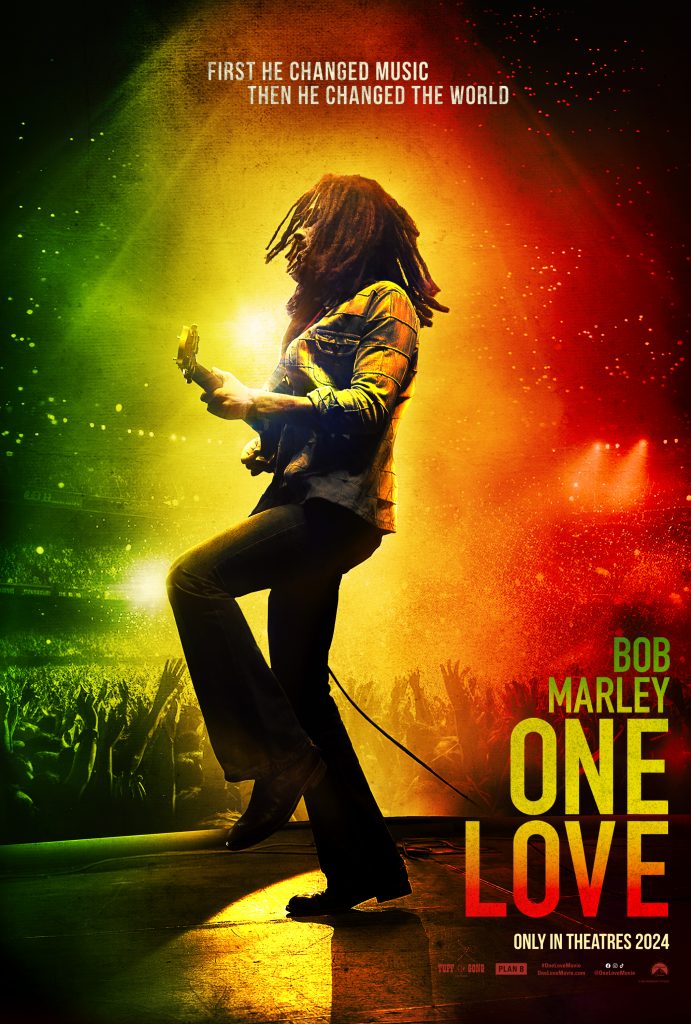

Bob Marely: One Love uncovers the man behind the music, tracing the legend as he embarked on Smile Jamaica, a politically neutral concert attempting to quell the country’s violence in late 1976. Marley’s origins and foundations are woven into a focused plot that depicts a specific period of the singer’s life. For the first time on the big screen, Paramount Pictures invites audiences to experience the heartfelt portrait of the reggae icon. The loving tribute celebrates and highlights the message that Marley brought to the world.

At last year’s CinemaCon, Ziggy Marley (Bob’s son and the film’s producer) introduced the first footage to exhibitors, sharing, “I am here as a producer of this film, but also as a steward of my father’s incredible legacy. More than 40 years after my father’s passing, his message of unity and love is as urgent as ever.” Produced in partnership with the Marley family, Bob Marley: One Love is directed by Reinaldo Marcus Green and stars Kingsley Ben-Adir as the lionized musician and Lashana Lynch as Cuban-Jamaican singer, and Bob’s wife, Rita Marley.

Bob Marley served as a big influence on screenwriter and Caribbean native Frank E. Flowers. After leaving the Cayman Islands to study screenwriting at the University of Southern California (USC), Flowers made his feature writing and directing debut in 2004 with Haven. His directing work includes numerous music videos for artists such Damian Marley and Ziggy Marley. With a passion for telling Caribbean stories, Flowers maintains a strong commitment to advancing Caribbean culture in film and serves on the Cayman Islands Film Commission. As a screenwriter, Flowers has scripted Metro Manila and Shooting Stars, which depicts the high school years of LeBron James.

Terence Winter is the Oscar-nominated writer behind such films as The Wolf of Wall Street and Get Rich or Die Tryin’. His prolific television career includes his work as a writer and executive producer on HBO’s “The Sopranos.” Winter wrote or co-wrote more than twenty-five episodes of the series during seasons two through six, garnering four Emmy Awards and twelve nominations, as well as three WGA Awards. In 2010, he created the series “Boardwalk Empire,” for which he also won a WGA Award and served as writer and executive producer. He was also the co-creator, head writer, and executive producer of the HBO drama series “Vinyl” and served as the showrunner and writer of “Tulsa King,” which he executive produced alongside series’ creator Taylor Sheridan.

Bob Marley: One Love has already broken records to become the number 1 midweek Valentine’s Day opening ever with a $14M launch at the box office. As the holiday weekend approaches, One Love screenwriters Terence Winter and Frank E. Flowers jam with Boxoffice Pro about writing the story of the Rastafari and bringing the ‘Skipper’ to the screen.

Capturing anyone’s life in two hours is a daunting task. How did each of you approach the project?

Terence Winter: Walking into it with that in mind, rather than try to tell a massive cradle-to-grave story, where it was just linear, we wanted to pick what we felt was the most pivotal period in Bob’s life. We landed on the period from 1977 up to his return to Jamaica a couple of years later. In doing so, we were able to flashback to pivotal points in his life. So I think we got the best of both worlds. You do have a little insight into where he came from and how he developed, but also, for us, this was the period of tumult and change and worldwide fame. We felt that was the most powerful way to tell the story.

Frank E. Flowers: I think with Bob, what’s unique is, in a weird way it would have almost been easier to say, “Let’s tell the life story of the greatest musician that ever lived.” Bob was not that dude. Bob was a man of the people. Bob was about humility. He said in his own words, my life is not important, what I do is important. This was also a pivotal moment where his message–his transcendent philosophy of loving one another and this kind of biblical, sacrificial, love all people narrative–was really hitting the world in a new way. His message was coming out. Terence and I were able to tap into this period, guided very heavily by Ziggy–who’s just the maestro of this entire process from script to screen. That message, what he was saying, was at its peak. That guided a lot of the process from an almost existential point of view.

What was your collaboration with Ziggy Marley like? You had a lot of early conversations in his living room talking about the story.

Terence Winter: It was surreal. It took me a beat or two to get it through my head that this is who I was sitting with. Frank E had known Ziggy for a while before that, so for me, walking into that house for the first time was pretty incredible. Once I calmed down, then it was just really easy and fun. We were not only with somebody who knew Bob as a father and loved him, but then got to go behind the scenes with Ziggy, listening to recordings that no one has ever heard before, seeing private photos, all of that stuff. We really went granular in terms of who Bob was and what he meant. Even watching interviews with Bob and having Ziggy narrate, “Well, this is what he’s really saying here.” It was just fascinating and an incredible luxury as writers to have access to somebody who was there. Then the rest of the family as well, friends, and people who worked with Bob. We had incredible access.

Does the family maintain an archive of materials that you were able to peruse?

Frank E. Flowers: The nice thing about someone like Bob, is that there’s so much material out there. Then there are these little kernels that only the family has, which are archived. To Terry’s point; Ziggy was the archive. Ziggy was also the first one to say, “All right, we have to check that or check this,” but so much of this movie is an intimate, personal portrait of a human being and his devotion to his message and his calling. Those are things that you almost can’t find in an archive. That was the beauty of sitting there. My family’s Jamaican, I’m from the Caribbean, so it was nice for me and Ziggy to be able to talk normally. We can talk in Patois, just break it down, and he can just flow and be honest. That’s really the essence of who he is: a generous, humble, honest, passionate artist.

How did you approach finding authenticity in the dialogue and bringing Jamaican Patois into the conversation?

Frank E. Flowers: There were different phases of it from a technical point of view. The very first draft was almost too much Patois. I’ve got to give it to Terry, because I figured I was going to have to do all that, and then Terry would be like, “No, let me take a stab.” I was like, “Oooh, okay.” Terry’s Patois was good; he was almost going further than me. There was a debate at first, “Will the studio understand this?” We actually found ourselves on a sliding scale of, “Alright, this draft we need to tone it back.” As they moved into production, they were able to ramp it back up. Kingsley and Reinaldo, they did their magic of diving deep. I have to applaud the studio for allowing them to be raw and real. When you hear this movie, it is authentic. I’m sure people are going to be googling things when they get out. They may not understand everything, but that’s so beautiful. And to not have subtitles.

Terence Winter: I was so happy about that too. There are moments in the movie where it doesn’t matter if you hear or understand every word. Look at the eyes of the people. There’s a moment where Rita and Bob are on the street going at it and you might not even catch a third of what they’re saying, but that doesn’t even need any dialogue. You can shut off the sound and you get it, you know exactly what’s going on. There’s so much there in the performances. It’s funny a writer to say this, because at some points, the dialogue is superfluous. So whether you get it or not, I love that it’s authentic and I love that people who know Patois feel that it’s real. That’s the best compliment you can get. That was a team effort.

Frank E. Flowers: By the way, that’s how I feel when I watch all those wonderful Irish films and TV shows where I’m just like, “This film is great. I don’t understand half of what this man said, but it’s great.”

Terence Winter: My grandmother was from Glasgow and my friends didn’t think she spoke English. They had no idea what she was talking about.

As an audience member, I loved hearing the Patois, because immediately I was leaning in and I was immersed. Frank E, can you speak to the importance of bringing Caribbean stories to the big screen?

Frank E. Flowers: I thank God every day for this privilege. To be able to be associated with a film of this caliber. I’ve always wanted to tell Caribbean stories. Those are my stories. I came to America when I was 17 to go to USC and learn screenwriting. As much as it was wonderful to learn the craft and the tech part of it, how to craft stories, there was always that thing of people kind of looking at you like, “Wait a second, are you ever going to tell something besides a story about the Caribbean? Are people going to understand this? Are you going to be able to get this made?” That’s a lot of fear, especially for the last 20 years that I’ve been in the business.

I have to applaud that Hollywood feels like it’s ready to embrace stories from all over the world. To see their value, critically and commercially. It’s not that it’s just some mission of goodwill—these movies work, they make money, and they reach audiences around the world. So for me, it really crystallizes that mission to continue to push for Caribbean stories and tell them authentically; for people to get the value of that and to enjoy that. We are all humans and we all have similar experiences, whether it be a love story or a tragedy, we’re all going through the same thing.

There’s something very poetic about Winter and Flowers. Can you talk about your collaboration together and how you like to work?

Terence Winter: That’s great. That never occurred to me before. That really is actually quite beautiful. Frank E and I have known each other as friends going on 20 years now. My wife Rachel introduced me to Frank E and I became a fan of his personally, then professionally as a writer/director as well. Over the years, we’ve worked together a couple of times. Most recently, Rachel and I produced the LeBron James biopic Shooting Stars, which Frank E wrote. He called me up five years ago and asked me if I’d be interested in collaborating on a Bob Marley movie. I don’t even think he finished the sentence, and I was like, “Are you kidding me? Of course. Absolutely.”

We were already friends and really loved and admired each other’s work so much. So it was a really easy collaboration and just a joy. When we started doing the research, I said, “Well, I’ve got to start reading as many books on Bob as they have.” He said, “Which one do you want?” He basically opened a drawer of every biography. He already had everything and knew everything. He kind of guided me and started my education. I knew Bob Marley as a fan and had all the music, but then did the deep dive into who Bob was. Then, of course, there were the meetings with Ziggy. It was just really fun. It’s a great collaboration.

Frank E. Flowers: I hate to say the word legend, because it makes it sound like the past, but Terry is one of those prolific writers in our business. It’s an honor and a privilege. I learn stuff from him every day yet he never flexes, he just makes us all feel like we’re real partners and we’re doing it together. One thing that Terry said to me on a previous project 10 years ago, which I’ve always admired is, “You write good scripts, the job is writing movies.” What Terry does better than anyone I’ve ever met, is that he can shape complex ideas.

One Love is about a person, but it’s also about a philosophy. It’s about a vibe. It’s about something existential. It’s about a man connecting with God and bringing a message to the world. Terry is able to shape that when he’s crafting it, and say, “This is what the studio will read, this is what the director will read, this is what the actor will read and this is how we put it into this movie form.” Unlike a novel, the ultimate form of this isn’t a script, the ultimate form of this is a film. Terry, with his experience and his gift, is able to do that in the most effective way I’ve ever seen and do it quickly from all his TV years. Terry could turn things around two days before the deadline and make it magic.

Terence Winter: I don’t think I ever wrote a term paper that wasn’t due the next day.

What was the evolution of the story? How did it take shape?

Terence Winter: You certainly could tell a linear story, which just felt extremely generic and unsatisfying. There’s also just too much story there. The period going into 1977 was this incredible, powerful moment that sent him into exile. Then in the next couple of years came worldwide fame, understanding who he was and what he wanted to do, and the triumphant return to Jamaica. That felt like a great bookend. It’s funny, we sort of stumbled on the idea that this was kind of the classic hero’s journey. There’s the trouble at home, he has to leave and learn about himself, and then come back a different man. It really lent itself to that structure and we felt that was the most powerful way to tell the story. For us, it’s the most interesting time of Bob’s life.

What excites each of you about storytelling and ignites your passion for it?

Frank E. Flowers: This process has really changed my entire perspective, not just as a writer, but as a human being. I connected so deeply with what Bob did. I read the Bible twice a day, I still do. It reignited my faith and my life. When I look at stories now, for me, it’s the excitement of sharing things about my culture, sharing things about the universal human experience and our place in the world, our connection to something bigger, and our responsibility to each other. That has really lit my fire and is driving the things that I’m working on now. Even if it’s an action movie taking place in the islands–I’m working on a pirate film right now–it’s really about connecting with the deeper truth of the message of the movie, of the characters, and that human experience. I’ve got to thank God and thank Bob for that.

Terence Winter: For me, it’s [about] connecting with people. From the time in which people were sitting around a fire talking about how they hunted down that elk, [stories have] kept people riveted. To be able to connect and tell a story and have people on the edge of their seat, or laugh, or cry. There’s no greater joy for me as a storyteller than to sit in an audience with people and watch something that I wrote have the effect I hoped it would have on an audience. There’s a moment everybody’s going to gasp at the same time. Everybody’s going to start crying, cheering, or there’s a big laugh coming. To know that you crafted a story in such a way that actually made people think.

I watch things that were made 100 years ago that make me cry. I watched a silent film recently by King Vidor called The Crowd. A guy’s daughter gets hit by a car and he’s carrying her up the steps. It’s a silent movie and I’m crying because somebody did that 100 years ago. I remember reading Tom Jones, which was written in the 18th century, and laughing. This guy from 300 years ago made me laugh. A good story will outlive you. It’ll be told. You watch sitcoms and Jack Benny still works for me–it’s still funny. To be able to do that is such a joy. That’s the heroin fix as a storyteller. I’m sure it’s the same with a singer or a comedian, to say, “Oh, this worked” or “Watch this” and see how people react to it. That, for me, is so satisfying.

Do you remember your first cinematic experience or a moviegoing memory that really shaped you as a writer and filmmaker?

Terence Winter: It certainly wasn’t the first, but it was the first movie that made me look at movies differently. As a teenager, I saw Taxi Driver when it first came out. I probably saw it 20 times that summer. I thought, “This is not like other movies.” I didn’t know why, but I was interested in finding out why and who this Martin Scorsese guy was and what else he had done. For me to flash forward decades later and to have worked with Martin Scorsese several times is mind-blowing. That was the moment where I realized this is not just going to a movie on a Friday night, it’s a whole other thing.

Frank E. Flowers: I grew up in the Cayman Islands. We had one theater and we got second run movies that would play for six and seven months at a time. I watched Predator and Die Hard more times than I ever wish to recall, but by the eighth weekend, nobody went to the movies to see the movie. The party was inside the theater. There was talking, fighting, cussing, and all that, so I didn’t grow up with that reverence for movies. Léon: The Professional was kind of the first time that I thought, “Oh wow, there’s something deeper to this.” I loved all those action movies, I love Predator, but there’s a different connection. When I came to America to go to USC, I think it was the first time I saw a black-and-white film in a theater. Foreign films also weren’t something that was in my lexicon or experience of film. To come and watch classics like Raging Bull and Citizen Kane, I was like, “Oh, wow, there’s a whole other layer to this.” I had kind of a different experience in that way, but equally as gratifying.

Share this post