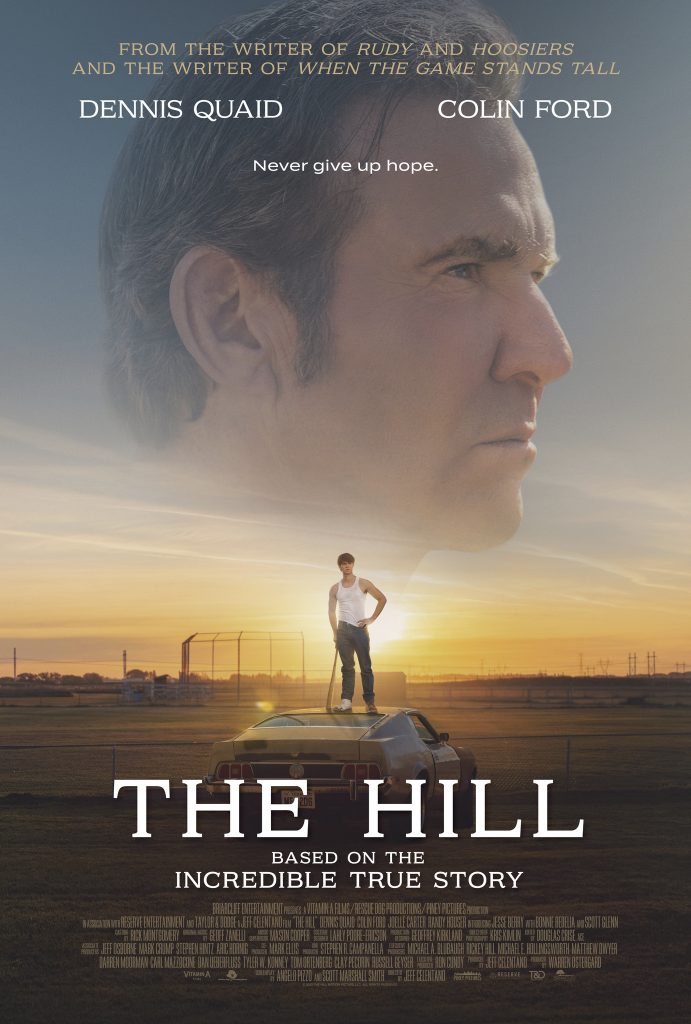

After nearly two decades in the making, director Jeff Celentano’s passion project The Hill is getting called up to big leagues with a big screen release this weekend. Briarcliff Entertainment presents the sports drama starring, Dennis Quaid as Pastor James Hill, the father of baseball prodigy Rickey Hill. Growing up impoverished in small-town Texas, Rickey Hill (played here by Jesse Berry and Colin Ford) shows an extraordinary ability for hitting a ball, despite being burdened by braces from a degenerative spinal disease. Rickey’s desire to pursue a baseball career divides his tight-knit family, threatening his dreams of becoming a heavy hitter. Arriving in the cinematic tradition of inspiring stories from the world of sports, The Hill hits theaters on August 25th. Prior to the film’s release, Boxoffice Pro spoke with director Jeff Celentano about his own inspiring story in bringing The Hill to the big screen. It all started back in 2006, when he first read the script and had the impulse to step up to the plate—or, in this case, the director’s chair.

I think it’s safe to say this is a passion project for you. It’s been a long time coming to the big screen. What were some of the biggest hurdles along the way? Outside of sheer determination, how did you beat the odds and bring this story to theaters?

The hurdles were immense. They were nonstop. A lot of my friends and people I’m close to [were] saying, “Give up on this movie. It’s never gonna get made. You’ve tried so hard. You can’t raise the money.” I always tell filmmakers, if you can’t ask somebody for money, and you want to be a filmmaker, it’s going to be hard. Some of the hurdles I went through were people saying they had money, saying they were going to fund the picture. Then spending months and months and months getting contracts with lawyers, only to find out they had no money. I have no idea why these people do this. It’s inherent in our business. People do it all the time. That was a frustrating, depressing situation for me. People would also say, “Okay, we’re going to fund the movie.” Then they would call my investor friend, who was the owner, and say, “We want to buy the movie from you for a lot of money, but we want to get rid of Jeff, because we have our own director.” [The owners] never gave up on me and never sold the movie out from under me, because I had so much passion. They just couldn’t take it away from me. They knew that this was my shot to do what I was born to do. I just felt like I couldn’t stop. It was something inside of me that said, “You’ve got to make this movie and not give up.” And they never gave up on me.

How did it all eventually come together?

Six years ago, I had the movie funded and we were in Oklahoma about to start pre-production. Dennis Quaid was hired. And all the money fell apart. The day the last piece of furniture came into the office, the money went out the door with it. That was a heartbreaker. Finally getting the money. To have it yanked out from under me was like ripping my heart out. That night at about 11pm, I was having dinner in a restaurant, because I hadn’t eaten the whole day. I was so upset. Dennis called me. I was terrified to call Dennis, because he had a Pay or Play deal. [The producers] were going to have to pay him. He called me at 11 o’clock at night and said, “Jeff, are you okay?” And I said, “No, I’m not. We have to pay you a lot of money.” He said, “Don’t worry about that. I love this movie. I’m on for life. I absolutely love the script. I love my character.” As Dennis said, “It has a lot of meat on the bone.” He said, “When you finally get the money, call me and I’ll do the film if my schedule permits.” I said, “We’ll just make the schedule permit for you. I’ll wait for you.” Six years later, boom, we got the movie made. Finally. An angel came from heaven, sat down and said, “I’m going to fund your movie.”

Biopics are notoriously tricky, given that so much has to be condensed into two hours. What was the script development process like, and how did Angelo Pizzo [screenwriter of sports classics Hoosiers and Rudy] get involved?

When I got this picture, I read the script and it was good–enough to get me to cry six or seven times. Then I took it to a friend of mine, who’s a big producer, and I said, “Would you read this and tell me what you think?” He said, “It’s kind of a Hallmark story, the way the script has been crafted. You want to make a big, epic, sweeping movie like Field of Dreams. You need an A-list writer to help you do that. Who’s your dream writer?” I laughed, and I said, ‘Well, Angelo Pizzo, Rudy and Hoosiers.” He laughed and said, “That’s a good wish, because, guess what, he happens to be one of my best friends, and he owes me a favor.” He added, “I don’t know if Angelo will respond to the material. We’ve got to send it to him.” So we sent it to him, and Angelo called us and said, “I love the story. I’m in.” So that’s how Angelo got on board.

Then I got Scott Marshall Smith to do a small polish and add some of the more faith elements in, because Ricky had that in his life. We didn’t want too much, because we wanted to appeal to the mainstream, but we also wanted enough to be honest to the story and truthful. Scott Marshall Smith passed away about a year ago at the age of 50. We’re all very sad, because he loved this movie and he never got to see it. Well, he’ll see it up there someday.

The real Rickey Hill serves as an executive producer. He also has a great cameo as a tryout coach, literally arguing with the younger version of himself. There’s also a great shot at a pivotal moment in the film of Rickey standing behind actor Colin Ford, who plays the teenage Rickey. It doesn’t detract from the story, but if you know who that is, it certainly adds extra weight to an already powerful moment. The scene is based on an incident that played out even more dramatically in real life.

Rickey actually jumped a 10-foot wall [in real life] and went up to [scout] Red Murff on the mound. And Red Murff said, “Son? Do you know where you’re standing right now?” Kind of disrespecting him. Rickey was crying, trying to get a chance to play, and they wouldn’t let him. He had been cut. Murph stood up on that mound—Rickey said he looked seven feet tall—and he looked down on this 17-year-old kid and said, “Do you know where you’re standing? You’re standing on the hill.” Rickey said, “I didn’t know that. I’m sorry, but I still want to play. I’m the best hitter you’re ever going to see.”

I didn’t have a choice hiring Rickey as the character. He came to me and said, “You are hiring me to play that coach that cut me.” My first reaction was, “There’s no way that’s going to happen.” And he said, “Why?” I said, “You’re not an actor, and this is a professional movie. We have a full crew. If you don’t know your lines, or you get nervous… It’s a lot different standing in front of me, telling me you want to do it, than [it is] standing on that field in front of the whole crew, with lights on, being examined under a microscope, and standing there with movie stars.” But he came out there and he did it. He was really into it. I cannot believe how great it is. I was so glad that he did it.

You are about to put your passion project out into the world at a time when faith-focused films are riding high at the box office and in a summer where moviegoers are rediscovering the theatrical experience. What is this moment like for you as a filmmaker?

I’m so exhilarated and excited that people are responding to it. I always knew the story was touching. I cried when I read the script. I cry every time I see the movie today. I’m not making that up. I’ve seen it 1,000 times. Never in my entire career have I watched a movie over and over and over and can’t wait to see it again. I’m watching it in New York tonight. We’re screening it for the Catholic Dioceses. Tomorrow night we’re screening for another group of filmgoers. I’m going to sit there through the whole thing. I don’t want to, because I’ve seen it so many times, but every time, I can’t get up.

I always knew it was going to be a good movie, but some movies go right to Netflix and you never hear about them again. What this movie is doing to people emotionally, I was not ready for. Randy Houser, the country singer that’s in the film, when I sent him the movie, he said, “I watched your movie, man. I watched our movie. I cried like a baby.” I was so surprised at the depth of what it’s doing to people. People have come up and told me that it’s changing their lives and they’re inspired. That’s how you feel when you walk out. You spend two hours of your time in a movie theater, you walk out and hope that you will be able to take something away with you. And this movie does that. I was not expecting that response.

It’s always great to see moviegoing within a movie. The neon marquee of the historic Knox Theatre in Warrenton, Georgia shows up here with a nod to American Graffiti, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this month. Did you grow up going to the movies? Do you have a favorite moviegoing memory?

I do! What got me into the whole movie business was Mary Poppins. I sat in that theater as an eight-year-old boy and looked up at the screen thinking, “Oh my God, it’s a fantasy. That whole world is a fantasy. I want to be in that world.” I started making little movies with our home camera. I was a surfer when I was a kid, and my mother would shoot me on the beach in New Jersey in the winter, if you can believe it, with snow on the beach. Me walking into the ocean with my wetsuit on, looking back and waving at the camera. Then I would take that little film and make a whole little surf movie out of it. When I started out my career as a director in 1994—I’d been an actor before that—I started cutting on Moviolas, which is a big old machine that the film goes through and you cut it. With movies back in the day, like The Godfather, you had to make really hard decisions as a filmmaker. You only had one piece of film. When you cut that film, that negative was your movie. You didn’t have alternate options. You had to really test it and think about it and talk to people. That’s what made those movies so great. I still carry that with me today.

Were there any films in particular that served as inspiration for your work on The Hill?

My inspiration, talking about Disney, was Seabiscuit. That movie was like a big warm blanket. You put it around you and you felt so good after you saw it, because that horse went through so much and just had a will of its own to win. It wasn’t going to quit, no matter what happened to it. That’s Rickey to me.

Share this post