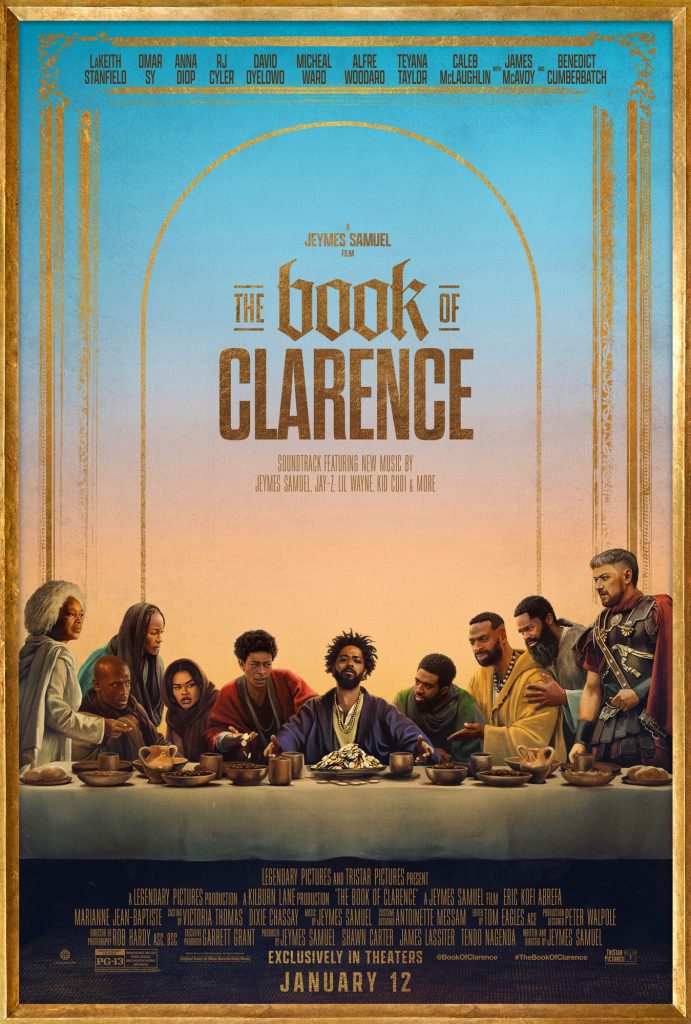

The Bible has served as source material for the big screen practically since the birth of the motion picture. Faith-based stories were particularly prominent in the 1950s when lavish widescreen spectacles such as The Robe, The Ten Commandments, and Ben-Hur topped the box office charts. Combining his love of such films with a desire to tell a story in a familiar setting, British singer-songwriter, producer, and filmmaker Jeymes Samuel presents a bold take on the biblical epic in Legendary Pictures’ The Book of Clarence. The story follows a streetwise Clarence (LaKeith Stanfield), who risks it all to follow in the footsteps of the rising Messiah.

As with Samuel’s previous film, the Netflix-released Western The Harder They Fall, he serves not only as the writer, director, and producer of The Book of Clarence but has also composed the score, written the film’s original songs, and performed those songs alongside guest artists, including his longtime friend and collaborator Jay-Z. In advance of The Book of Clarence’s January 12th release from Sony/TriStar Pictures, Boxoffice Pro spoke with Samuel about crafting his own distinctive vision of a biblical tale.

Biblical epics were flourishing at a time when movie theaters were competing with the advent of television. The 1953 biblical epic The Robe was the first film in 20th Century Fox’s anamorphic widescreen format CinemaScope. Widescreen processes from the other studios followed, increasing the size and scope of the screen. How essential is the theatrical experience to this film?

It’s immeasurably important because it’s the first of its kind in 135 years of the moving image. When you’re watching something so singular, you don’t want to give an option for the viewer to pause. It’s a huge thing. When you go to the cinema, no matter how much you like the film or you don’t like the film, you don’t have the option to pause and go to the toilet. Some experiences you have to experience on a big screen, in the dark, communally with strangers. You need to be served the plate in one sitting. It’s immeasurably important.

Structured in books, the intertitles in The Book of Clarence provide a callback to the big cinematic event of a biblical epic.

Exactly. In VistaVision. In CinemaScope. That was hugely important for me. Even the opening titles. The opening titles are a wink to a hybrid between old-school biblical movies like Quo Vadis or Ben-Hur and the opening title sequence of “Taxi”, the old Danny DeVito TV show where taxis are driving over the bridge. I wanted it to be a wagon driving through Jerusalem. You used to see “Judd Hirsch in Taxi” over the score. I wanted “LaKeith Stanfield in The Book of Clarence.” The word “in” is hugely significant, because you’ve never see that word in the opening titles. You don’t see it. You just watch “Tom Cruise,” “Mission: Impossible.” So to say “LaKeith Stanfield in,” and then the song starts [sings]: “The Book of Clarence.” Everything about this film is cinematic, which is why it had to be in the cinema.

You’re taking familiar stories but placing them in an environment that hasn’t been seen in a biblical epic before.

What’s unique about this film is that it’s an environment that we see every day. I wanted to tell a story that looks like the environment I grew up in, but based in the biblical days, to show how closely knit those two are. The story takes place in the hood. In every single country, in every universe–even a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away–there’s always the hood. Luke Skywalker lives in the hood on Tatooine when we meet him. The Jawas are the gangbangers. The Jawas and the Sand People are like the Bloods and Crips of Tatooine. In every single world, there’s a hood. I wanted to tell a story about the hood and have it look like the environment that I grew up in, but based in biblical days. That was of the utmost importance to me, because I love those films so much.

Like many of those films, you’ve assembled an all-star cast, but there’s a focus on inclusion and diversity in your story that brings a fresh perspective to the biblical era.

Absolutely. For me, art is all about expression, freedom, inclusion, and diversity. I’m purposely not making a commentary on race or color in this movie, but I really wanted to put a spotlight on diversity and inclusion. Women have a strong role. In this movie, the fastest person on a chariot is a woman from the streets, Mary Magdalene. Inclusion was a huge thing for me because that’s one thing that was missing from those biblical epics. Even though they were all talking about freedom, they were the least diverse when it came to casting. They were the most exclusionist forms of cinema. If you asked me what Jesus looked like growing up, I would have sworn blind that he looked like Robert Powell from Franco Zeffirelli’s “Jesus of Nazareth,” which was the television miniseries that broke all records at the time. It was amazing. With James Mason, Stacy Keach, Ian McShane, Robert Powell. Everyone is in that movie, but no one who looked like us.

That idea of what Jesus is “supposed” to look like plays into this film as well.

That particular scene is a commentary on my parents’ generation’s fascination with a white image of Jesus, a particular old-school image of Jesus. We all had those paintings up in our house growing up. In my house, we had a 3D image framed in the living room of white Jesus on the crucifix. It was 3D, which meant wherever you went in the living room, Jesus was looking at you. It was a really scary image. I used to look at it for ages. You could not escape the gaze of crucified Jesus. So I wanted to put in a humorous commentary on my parents’ generation.

You’ve talked about LaKeith Stanfield as a superhero of ideas on set. What was your collaboration like on this project?

A director is really fortunate when he can find an actor that occupies the same space. LaKeith would say that I gave him direction, but if you looked at us working, you’d just see us laughing and having mad fun. It was almost like directing myself. There wasn’t anything I had to tell him to do in a different way. Sometimes I’d walk up to him and go, “Oh man, I just had an idea.” I would explain it to him and he’d say to me, “You need to get out of my head.” He would have the exact same idea. His instincts for the roles that he played [LaKeith plays more than one character in the film] were astounding. It was the most dreamlike scenario having LaKeith play the lead of Clarence. He surprised me as well because what I learned about him is that he’s really physical. During the gladiator fights, he has to jump and roll over actor Omar Sy’s back. Omar Sy is a big, six-foot, three-inch physical titan. LaKeith would just go toe to toe with this dude. It was an amazing thing. Directing him was just a dream.

You’ve spoken in the past about “obeying your crazy.” What does your creative process look like, balancing all the different roles you’ve taken on for this film?

I suppose it looks crazy, but to me, the whole world is crazy and I’m the same way. For instance, I believe composers come onto a film too late. When a composer starts working on the film, the film’s already shot. I believe the composer should be working from the script stage before anyone is cast. A composer should be coming up with themes, motifs, and dramatic signatures, because if you know how your music sounds beforehand, you can choreograph your camera in alignment with your melodies, your motifs, and your themes. If you watch me, everything’s happening all at once. As I’m speaking to an actor, I’m also singing a song that plays in the background.

When the apostles have the revelation that Judas is the traitor, I was telling Micheal Ward, who plays Judas, the rhythm in which I needed him to be uncontrollable with the dip of the bread in the gravy. I explained to him [the scene’s] music, and because I know how the score goes, I know the rhythm in which to tell him [to move]. Everything is happening all at once. There’s not a single day or moment where I don’t play music on set. So everyone feels the environment and feels what I’m doing. If there’s no dialogue in the scene, I’ll play the score for it in the background. It’s all just one continuous creative stream. All of the actors, the production designer, the first assistant director, everyone pops into little boats and rows on my creative stream and we make the movie together. So it does look crazy, but it also looks immensely fun. From The Harder They Fall to The Book of Clarence, I don’t believe there’s another movie set in existence that’s like a Jeymes Samuel set.

In the same way that Western movies have informed what we think a Western score should be, there is a certain type of score associated with biblical epics. How does your score bring a new flavor to old times?

I take everything I’ve seen and heard and learned and I deconstruct it. You get everything you know and are familiar with biblical-era scores, which I love. I love Alex North’s score for Spartacus. I will bring that straight into—not even 2023, I will bring it into 2043. Pino Palladino, the best bass player in the world, plays bass throughout the scope of this movie. While you have a grand biblical epic score, you also have Palladino on the bass, James Poyser from The Roots on the keys, and Isaiah Sharkey, one of the best guitar players in the world, on the guitar. So you have all this new instrumentation, as well as the old-school scores. I write, produce, and perform all the songs on the soundtrack with featured artists. The songs weave in and out of the score, so you have this incalculable modernity running alongside and intertwining with this huge, epic score. It’s literally one of a kind.

Part of the message of the film centers around the stories each of us tell and the knowledge that anything is possible.

Clarence is a person who is in alignment with me as a human being. I do not believe in the word “dreams,” nor does Clarence. Somewhere along the way, an influential but misguided man changed the words “plans,” “intentions,” and “aims” into “dreams.” Our dream car, our dream house, our dream job, but you show me a dreamer and I’ll show you a failure. You can’t hold a dream; you have them when you’re asleep. As human beings–especially people from impoverished or oppressed backgrounds like myself–we have to rid ourselves of that word, “dream.” We have plans, we have aims, we have intentions, and they’re all real.

Clarence is a person who thinks big. In his mind, he can do anything, which is why he’s always saying knowledge is stronger than belief. He honestly knows he can do anything, so he plans all of these things and gets himself into hot water as a result. Clarence is a person who thinks big, and for him, they’re not dreams. He wants to become the new Messiah. That’s an outlandish thing, but Clarence is just the type of person who will pursue it. For him, nothing is out of his reach. Now, obviously, I don’t want people to be misguided in their aims, plans, and intentions, but I do want people to know that anything is possible. Even for me, as a filmmaker coming from Kilburn Lane, Mozart Estate–one of the hoodest hoods in London—I made a movie about the Old West. I made a movie about the New Testament. They’re all real things. None of them are dreams. Not in alignment with religion, but in alignment with our lives, I do want people to know that knowledge is stronger than belief.

What is your favorite moviegoing memory?

I was a child, and Spike Lee had made Do the Right Thing. We didn’t know what he was going to do next. This guy would release a movie almost every year it seemed. His next movie was Mo’ Better Blues. I was too young to get into the theater, but my cousin took me to see it for my birthday. For Mo’ Better Blues, I had all these questions as a kid: “What is Spike Lee, this magician, this wizard, going to do next?” The Universal logo comes up. This is one of my favorite moviegoing moments of all time. It’s the first time I’d seen an opening logo remixed. You heard Flavor Flav talking, and he spelled out Universal. “U-N-l-V-E-R-

S-A-L. Universal. Y’all been large for years. Yo, Spike, start the movie, G. Flavor Flav, you’ve done it again.” [Gasps.] And the movie starts. My brain was like the solar system opening.

Spike Lee was free. He was free of all constraints. He was free from all shackles. He was free from every single rule in the rulebook. He was black. He was from the hood. He was remixing logos. This guy was the most misbehaved director, for me, in the history of Hollywood. We’d never had that. Spike Lee set the course of what was to come with directing. After that, everyone was misbehaved.

Share this post