For any filmgoer who lived in New York City in the 1960s and 1970s, the name “Cinema 5” was as familiar as that of Loews or Trans-Lux. Cinema 5 was the premier art-house circuit in Manhattan, comprising an array of stylish theaters including the Beekman, the Sutton, the Paris, the Plaza, the Paramount, and the Gramercy. Single-handedly, company founder Donald Rugoff turned New York’s Upper East Side into a cinema mecca. His Cinema I and II was the first purpose-built twin movie theater in the country and soon became a sought-after venue for the exclusive runs of major Hollywood releases. Woody Allen insisted his movies open at the Beekman; Mel Brooks always wanted the Sutton.

Cinema 5 was also a major specialty distributor. Among its breakout hits were the landmark surfing doc The Endless Summer, Oscar Best Picture nominee Z, the Rolling Stones doc Gimme Shelter, Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, Lina Wertmüller’s Swept Away and Seven Beauties, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, and the film that introduced Arnold Schwarzenegger to movie audiences, Pumping Iron.

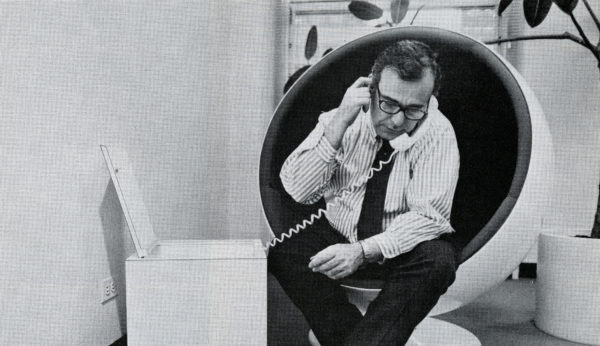

Rugoff was a man of taste and a true visionary, but as Ira Deutchman’s documentary Searching for Mr. Rugoff shows, he was also a notoriously erratic and unpleasant boss. Deutchman worked for Cinema 5 for three years and witnessed firsthand his tantrums, his shocking unkemptness, and his tendency to fall asleep during meetings and screenings. Rumors circulated that he had a metal plate in his head—not true, though he did battle a serious pituitary disorder. Rugoff lost control of his company in 1979 in a shareholder battle with West Coast exhibitor William Forman. He retired to Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard in 1986 and opened a makeshift cinema in an old church. He died three years later.

Deutchman was inspired to make his documentary after hearing another New York distribution/exhibition legend, Dan Talbot, pay tribute to Rugoff at the Gotham Awards, stating incorrectly that he died “in a pauper’s grave” in Edgartown. The first-time filmmaker soon discovered, however, that this major force in the New York film world was all but forgotten, with little to be found on the internet.

His apprenticeship with Rugoff changed Deutchman’s life. In 1981, he joined the team at the newly transformed United Artists Classics, overseeing marketing of such films as Diva and The Last Metro. One year later, he founded Cinecom International, which released such important films as El Norte, Stop Making Sense, Matewan, and Oscar Best Picture nominee A Room with a View. In 1990, Deutchman founded New Line specialty division Fine Line Features, whose triumphs included Robert Altman’s The Player and Short Cuts, Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho, Steve James’ Hoop Dreams, Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth, Mike Leigh’s Naked, David O. Russell’s Spanking the Monkey, and Whit Stillman’s Barcelona. Subsequently, he produced such films as Lulu on the Bridge and Kiss Me, Guido, and he founded another producer-distributor, Emerging Pictures, a pioneer in alternative content for alternative venues. Deutchman has taught in the film department at Columbia University since 1987, serving as chair of the film program from 2011 to 2015 and founding Columbia’s Digital Storytelling Lab with Lance Weiler in 2013.

Searching for Mr. Rugoff, whose on-camera subjects include Rugoff’s first wife and two sons, filmmakers Costa-Gavras and Lina Wertmüller, and many veterans of the New York film business, debuts this Friday at theaters and in virtual cinemas. Here, Deutchman talks about the legacy of Don Rugoff and his own storied career.

The film is a such a nostalgia trip for me, because I went to college in New York in the ’70s and I spent a lot of time in Cinema 5 theaters, and I remember those marketing campaigns vividly. I was as shocked as you that Don Rugoff is so forgotten today.

It shocked me too. That was one of the things that inspired the movie. I talked about him for decades and decades, mainly telling stories about his not so great behavior and how crazy he was. And then one day I was at a film festival and there was a group of people around me, and as I was telling stories about this outrageous guy, I realized nobody knew who he was. That’s what got me going.

What do you think made Rugoff such a success story in his heyday?

I think being crazy was part of it. This is kind of a cliché, but a lot of people think you have to be at least a little bit crazy to be interested in being in the film business. I think that sometimes when you look at the world askew and you’re not necessarily being completely logical and businesslike, you end up taking the kinds of chances that sometimes pay off. That was part of his brilliance. He was more of a carnival barker than he was a businessperson, in contrast to a lot of other people who attempt to make things go in the film business and are surprised when there’s no formula that they can put in a spreadsheet and make things work. I would say that that’s one of the biggest lessons I took from working at Cinema 5, that there was no logic to any of it and you had to go with your gut instincts. He had no compunctions about doing that. If he saw something and thought there was an angle that he could exploit, he would just go for it.

The Cinema 5 posters and marketing campaigns were so graphically interesting and vivid, I almost got the impression that everything he touched at that time was a success. Do I have the wrong impression?

You definitely have the wrong impression. He had a few periods where what he touched turned to gold, and then lots of fallow periods in between. The vast majority of films that he distributed during that 15 to 17-year period were not that successful, but here and there he had something that broke through. There’s a line in the movie from Jim Hudson, the CFO, something that he wrote in the annual report: “Critical acclaim exceeded box office grosses.” He thinks that’s funny and it is, but the impression of success came very much from the fact that these were acclaimed movies. Rugoff definitely made a lot of noise for every movie he put out there, and he refused to give up. So they had a longevity in the marketplace that wasn’t necessarily the right business decision—it doesn’t necessarily add up to making money.

What are some of the lessons you took from your time at Cinema 5 that you brought to your later career?

Bottom line is that it’s not easy, nor has it ever been easy, to get butts in seats, at least once there was competition for the movies. A lot of people think that this is a new thing because of what’s going on with the streaming world right now, et cetera. And I keep talking about how we’ve been living this nightmare for a long time. The era that Rugoff was operating in was not dissimilar—everybody was worried that television was becoming a mass medium that would put movies out of business, and it just created a business opportunity for somebody who looked at things a little differently. I think the same thing is potentially true now. Everybody who’s moaning about how awful things are—what I took away from my Rugoff experience was: Think differently. Don’t look at the marketplace and say I want to do what other people are doing or whatever the last success was. Think about, oh, this is really different from anything out there and there’s a way that I could make noise with this. It still works.

You saw Don Rugoff up close up for a number of years, but were there surprises as you researched him?

It really played out in life the way it plays out in the movie, which is that I never understood quite what his illness was. I never knew when it started and how far into it he was at the time I worked there. I never was able to put together the whole picture of his behavior and what might have been the cause of it. I didn’t know anything about his personal history, and then of course there was all this stuff that happened after I worked there, which is what sort of set me on the journey to begin with, trying to figure out why he completely disappeared. It didn’t make it into the movie, but one of the people I interviewed said something to the effect that when people get fired or kicked out of companies in the movie business, it’s pretty standard that they have a second act or third act. But in Rugoff’s case, he just completely disappeared once he was out of Cinema 5. Now that I’ve done the research and talked to all these people, I sort of get it. He burned every bridge, nobody really wanted to do any business with him at all. And he was not the type of personality who could just go work for somebody else. Now it makes sense to me, but I didn’t really understand that at the time.

Were there many times when you thought about quitting Cinema 5?

I quit three times. That was in the movie at one point, but you have to make choices along the way. But yeah, I quit three times. Every time I quit, I got a raise and a promotion, so it was really good for my career. I sort of caught on after a while.

Boxoffice recently ran a section on the centennial of United Artists and had a sidebar about United Artists Classics. I was amazed by the legacy of the people who worked there. Did you have a sense that this was a special group at the time?

I don’t know about a special group. I knew that what we were doing was special, and it’s funny that you bring that up, because I do think that UA Classics to some extent was a real extension of the Rugoff way of doing business. I don’t want to toot my own horn, but I think I brought some of that with me without realizing it—the whole marketing skew. I was running marketing at UA Classics from the moment that we started doing first-run films. I didn’t necessarily want to be doing that, I needed a job. but the fact is that that I was definitely aping much of what I had seen Rugoff do, in terms of not only the movies to get behind but the whole process of the way that we bought media, the types of ads we were running. A lot of those early UA Classics ads, if you look at them closely, resemble Rugoff ads, and I don’t think that’s an accident.

Cinecom had this great triumph with A Room with a View. At the time, I thought the company would have some longevity. Why did it end?

Good question. It’s definitely another Rugoff lesson. The truth is that you’re going to see it happen again and again and again with other companies. The minute you have a mega success on your hands, it goes to people’s heads. They think that all of a sudden they know the magic that other people don’t know. And it goes back to what I was saying earlier about the fact that you don’t look at what already was successful to plan your next success. What you do is try to look at what nobody else is doing. When A Room with a View was as successful as it was, there’s no doubt that the company overextended itself and got involved with much riskier films. If it had stuck to its knitting, I think it might have lasted a whole lot longer. Your recollection might be a little skewed, because it didn’t flame out that fast. The company existed for at least another five, six years after A Room with a View and actually had some other modest successes during that time frame, but nothing as big A Room with a View was.

You’ve championed many female directors that over the years. What motivated you?

It’s actually pretty simple. I certainly was not thinking ahead to the era we’re in right now, but what I was thinking about, again, is what can I do that’s different from what everybody else is doing? And that just led me in that direction, because there were an enormous number of really talented female directors who weren’t getting a shot. From my perspective, it meant that this was ripe for the taking, to discover whoever was out there, and a lot of those people went on to have a fair amount of success within the limited world that they were allowed, given the fact that Hollywood was not opening their doors to them.

We both come from a generation where foreign-language films really had some box office clout, and now a movie like Parasite is more of a rarity. What do you think has changed?

It’s funny because, again, I feel like we have a tendency, all of us from that generation, to romanticize things. But the reality is that foreign-language films being that successful were always the exception. There were plenty of films that were released. The only difference is that the ones that don’t break through do way worse now than they did then. There was a cottage business in being able to do foreign language films that could gross a million, a million and a half. If you handled them frugally and really focused on the target audience, you could make money on films like that. But nowadays those same movies might do $50,000 at the box office. The lower end has dropped off tremendously. But the ones that really crossed over it and did big business, those were always few and far between.

Also, it was an era where you had these names like Fellini and Bergman and Truffaut.

And Bong [Joon Ho] has made his mark now as one of those people. I’ve actually pissed off a lot of people by saying this, but the French New Wave was one of the greatest marketing schemes that anybody ever cooked up. I’m not kidding when I say that. When you can gang films together under an umbrella where people start to look at them as somehow being related to one another, then you’re in effect doing the same thing that people are doing now when they talk about how much easier it is to market a sequel or an episodic thing, because it’s kind of pre-marketed. But when you have something like the French New Wave or other movements like that that have been identified, it just gives you an easy hook to get people interested: If they like this film, maybe they’ll like that film. And directors’ names were like that too, they were brand names. And while we have social media at this point for people to extend their brands, the truth is that it was the press and film festivals that helped us to establish the brand names of these directors. And then once somebody was a brand name, the new Truffaut, the new Fellini, it actually meant something.

I think critics had more clout, too. Vincent Canby would champion Fassbinder, and Pauline Kael had her favorites, and that was part of the marketing power of these films.

That’s definitely true. In those days, there were more critics who had more clout than is true today. The people who are working for the biggest-circulation publications still mean something, but there’s a lot of regional press that doesn’t exist anymore. There used to be a plan B if the film didn’t get a good review in The New York Times. There was actually someplace else to go.

Because you’re a big part of the film department at Columbia University, I’m curious what today’s cineastes are like and how they’re different from the cineastes of our generation.

That’s a really good question. And interestingly, I would have answered it very differently had you asked me that question 10 years ago. I think things are better now than they were then. There was a moment in time where I was getting really despondent because when I was quizzing students at the school, it seemed like film histories began with Quentin Tarantino and ended with Quentin Tarantino. Now I think the students have seen so much more and have such a wider range of taste. I did a show of hands in my class just last week about how many people had seen The Lighthouse in its opening week and half the class raised their hand. I was like, all right, I like this generation.

How do you feel about the future of theatrical film and movie theaters?

Well, I’m going to sound really Pollyannaish. I refuse to believe that this existential crisis is any worse than the last five existential crises the theatrical movie business has been through. There have to be changes. and that’s not new either, because the business has evolved all through its history, both through new technologies and new business models. There’s been a resistance to every advance that’s happened in terms of films getting into the hands of consumers, and then when the resistance stops, all of a sudden they find out that there’s actually a way to make it work, that there is a compatibility. I think that we’ll reach another moment where there’s going to be some stability. The major studios are in a really awkward spot, because the kinds of risks that they have on each film are just so extreme in terms of what the marketplace can support on a predictable basis.

There’s no doubt in my mind that the consolidation that’s going on in the business is going to continue. But I think that there’s always going to be a really enthusiastic group of people who are going to want to see movies in movie theaters. And I don’t necessarily think it’s going to have anything to do with exclusivity. I do think it’s going to have something to do with the pricing model and also with the kinds of experiences that people are given when they go to the movies. I honestly don’t think it has anything to do with reclining chairs and the sound being so deafening that you can’t even hear yourself laugh at a comedy. I think that all the wrong solutions are being looked at at the moment, but the movie business will survive.

Part of that is the communal experience. Do you think people still have a hunger for that?

It’s all about that. And if you really look closely at some of the businesses that are rebounding from similar existential crises, like the music business and the book business, there’s a side of the younger generation that wants authentic experiences and there’s nothing more authentic than seeing a movie in a movie theater.

You are a pioneer in the field of what they call event cinema, and it looks like it’s getting some traction. Where do you see event cinema headed?

I think event cinema is going to be part of the future on a more ongoing basis. The whole idea that we’re stuck with a world in which movies have to play seven days a week, four shows a day, has been one of the limiting factors in everybody making more money. I’ve always been a big believer in taking a single screen and multiplexing it and having different films play in different day parts. I believe that the business model for theatrical is going to evolve in some way, and that’s going to be part of it.

We just ran a piece on the theatrical production of Fleabag, which started as event cinema but the IFC Center is actually booking it for a regular run. The lines are being erased a little bit.

I think there’s going to come a day where a film is going to premiere on some sort of streaming network and then it starts to catch fire and they’ll pull it and put it into movie theaters. Or just think about how much money HBO could have made if they had put the finale of “Game of Thrones” into movie theaters a week before it was shown on HBO.

You’re developing Nickel and Dimed, based on the book by Barbara Ehrenreich. Can you give me a status report on that?

Debra Granik is going to be directing it. It’s in a form of pre-production already, and we’re going to be shooting it next fall. She’s in the process of doing her research on it right now. The film is financed, so we’re ready to go.

What a great filmmaker to have on your team.

She’s an amazing person and I’m glad that she’s going to get the opportunity to adapt that book, because it’s a perfect match.

You’ve been in marketing and distribution all these years. How does it feel to have completed your first film and get it out there?

It’s a major relief. It’s hard to believe that it actually became a movie, to be honest with you. Along the way I wasn’t really sure what it was gonna turn into. The very first time I saw it strung out—we hadn’t really done any sort of fine cutting yet, but when I saw it from beginning to end for the first time, I had to pop open a bottle of champagne because it was like, oh my gosh, this is actually resembling a movie.

Share this post