It starts with a bang—literally. After the opening Disney logo fades, the very first moment of Toy Story 4 is a lightning crash.

And the rain looks like nothing you’ve seen in animation before. To create their cutting-edge graphics and imagery, Pixar uses its own “render farm,” a massive supercomputer that ranks among the 25 largest computers on the planet. Pixar used a 294-core render farm during production of the first Toy Story. The latest installment employed an astounding 55,000 cores.

On-screen, this produces a level of detail that may be Pixar’s highest yet. In Pixar’s earliest films, “rain” consisted of vertically falling dots or lines. But for Toy Story 4’s opening sequence, a nighttime toy rescue during an intense thunderstorm, every single one of the thousands of water droplets interacts with its environment—bouncing off surfaces, for example.

One of those surfaces is an Easter egg: a car with the license plate RM-R-F*. That’s the keyboard command that caused a Pixar employee during production of Toy Story 2 to accidentally delete the entire film from the company’s internal system. Fortunately, another employee, home on maternity leave, had saved a backup copy to work on at home.

The third time was the charm

The dramatic rescue opening is the tonal opposite of where the series left off after 2010’s Toy Story 3.

Andy was heading off to college after giving his childhood toys away to a girl named Bonnie. But during the tearjerker ending, he takes his old friends out of the box one last time after years of collecting dust, and rediscovers the childhood sense of magic and adventure he’d been so desperate to shed.

The closing shot panned up from young-adult Andy to clouds in the sky, a self-referential homage to the original installment’s opening shot of clouds on little Andy’s wallpaper. The implication: The narrative had come full circle and the series would forever remain a trilogy. Or at least it seemed that way.

After all, the series had gone out on the highest of high notes. It became the highest-grossing movie of the year, the last animated film to earn that distinction. Not only did it win the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, it even received a nomination for Best Picture—also the last animated film to do so. Even Quentin Tarantino, whose oeuvre is Pixar’s opposite in nearly every respect, proclaimed it his favorite film of that year.

Given that pedigree, expectations for this fourth installment have been through the roof. What was the biggest challenge? “Executing the ending,” director Josh Cooley says, well aware of the predecessor’s near-perfect conclusion. “But I know we did that, because we just watched it with the music that Randy [Newman] wrote and I was tearing up!”

Go fourth

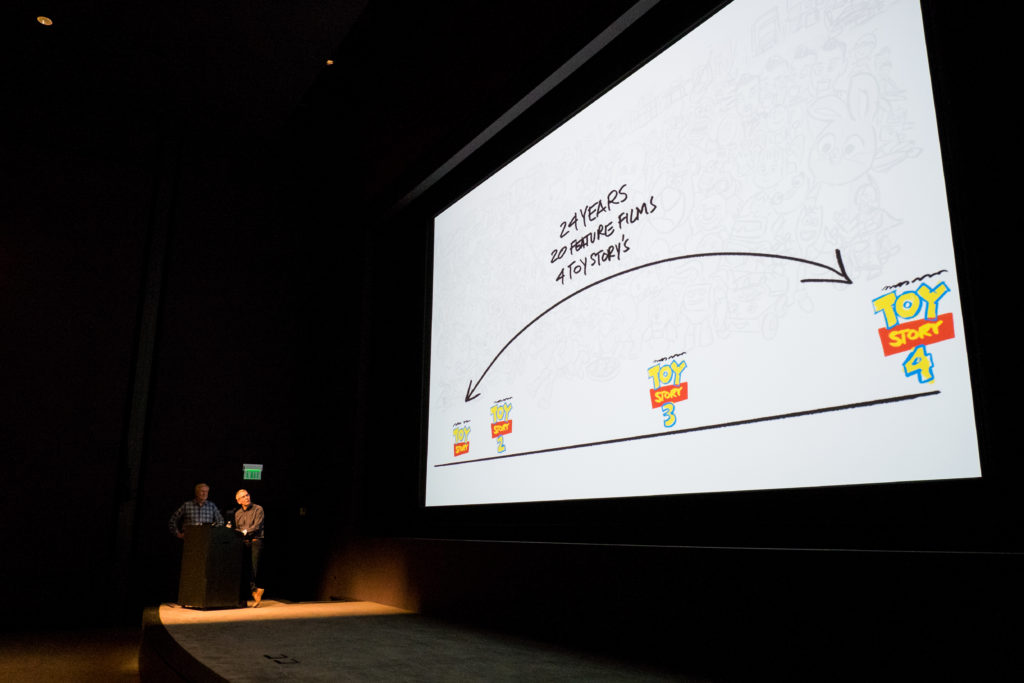

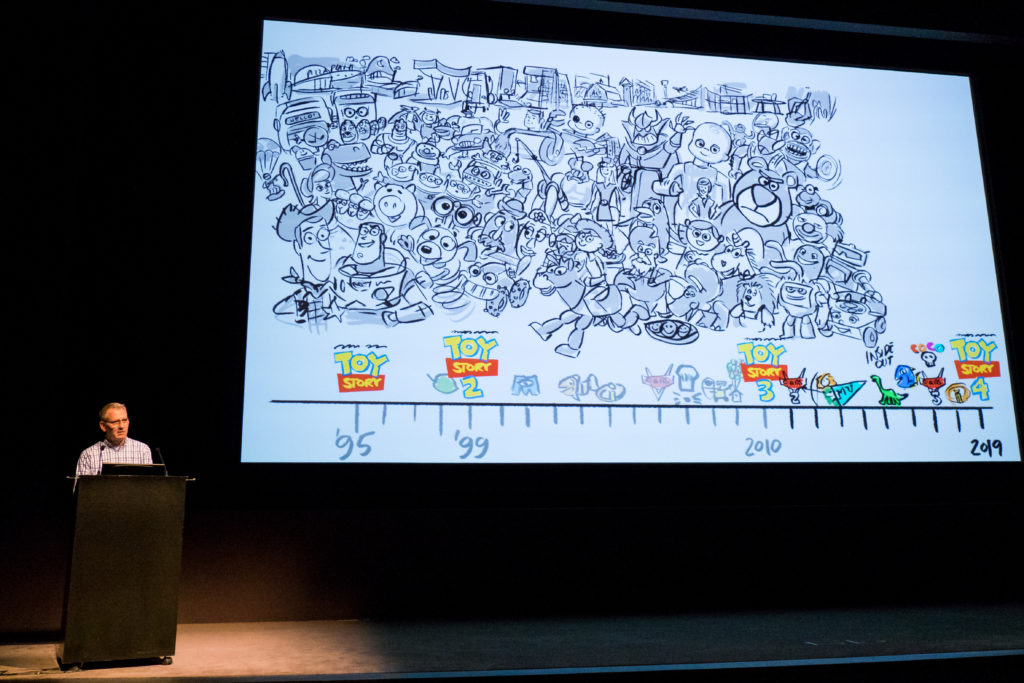

If the third film ended so flawlessly, why this fourth installment? Presumably, because in the past decade Pixar has produced more franchise installments than standalone films. After spending most of its early history producing entirely original films, the studio has turned to making sequels or prequels (seven of its last 11 films, including Toy Story 4,).

Financially, this guarantees a smash. Of Pixar’s 20 releases to date, three have earned $1 billion globally. All three were sequels: Incredibles 2, Finding Dory, and Toy Story 3. Many are predicting that Toy Story 4 will reach that vaunted billion-dollar threshold too.

Domestically, the numbers tell the same story. Adjusted for ticket-price inflation, four of Pixar’s top five films at the North American box office were sequels. (The one original to crack Pixar’s top five earners? Finding Nemo.)

That recent focus on franchises, however, has been a trade-off, partially impacting the company’s 1990s–2000s reputation for producing Hollywood’s best original content. Sorting Pixar’s films by audience score on Rotten Tomatoes and IMDb, almost all of its 2010s sequels or prequels—all except Toy Story 3—rank in the bottom half.

Of Pixar’s five most recent originals, four won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. But of its five most recent sequels or prequels, none has.

Snags along the way

Toy Story 4 never faced an obstacle as existential as an accidental deletion. Nonetheless, it experienced many more road bumps than expected en route to its June 21 theatrical release.

First announced by Disney for summer 2017, it was delayed a year, then yet another year to summer 2019. Pixar president Jim Morris originally announced the film as essentially a romantic comedy between Woody and Bo Peep, his shepherdess love interest from the second installment—an idea later abandoned as the main plot.

The directing credits partially changed, too. Josh Cooley began as a Pixar intern, later getting hired as a storyboard artist and directing the animated short Riley’s First Date featured on the Inside Out DVD. Without even asking or applying for the position, he was tapped to co-direct Toy Story 4 as his first feature film, alongside John Lasseter, who had directed the first two installments. It seemed like an ideal combo: the veteran plus the fresh face. But when Lasseter later dropped out as co-director (ultimately leaving Disney under a cloud of sexual misconduct charges), newbie Cooley was left in charge.

Cooley committed to doing right by the franchise. “My first time seeing Toy Story was in theaters with my brother,” Cooley says of the first-ever full-length 3-D animated film. “I had wanted to do 2-D animation, because until then I thought 3-D animation would blow over!” On that day, though, he changed his preferred medium forever.

There were also screenplay challenges. Pixar cut most of 4’s original script, co-written by Rashida Jones and Will McCormack, replacing them with relative newbie Stephany Folsom, who would receive her first feature-film screenwriting credit. Folsom had earned the job largely due to positive word of mouth about her unproduced screenplay 1969: A Space Odyssey, a satire about NASA faking the moon landing.

“She just had this really great sense of character, plot, pacing,” producer Jonas Rivera says. “She was able to track this complex story where things jump around. We talked to her, and it just kind of gelled.”

Finding your voice

In addition to the returning leads—Tom Hanks as Woody the cowboy sheriff and Tim Allen as Buzz Lightyear the space ranger—several new characters join the ensemble.

Comedy duo Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele play Ducky and Bunny, respectively: two prize toys in a carnival game called Star Adventurer. Peele voices the tall character while Key voices the short character, a sly reversal of the two comedians’ heights in real life. They recorded all their lines together rather than having their individual readings merged during production.

“It’s the most fun we’ve ever had recording,” producer Mike Nielsen says, “ever.” He gives an example of an improvisation that made it into the final cut. Key’s Ducky can’t reach something, to which Peele’s Bunny asks why in a faux-innocent voice. “You’re really gonna make me say it?” Ducky replies incredulously. “I’ve got these tiny little legs!”

Keanu Reeves joins as a 1970s-era action figure named Duke Caboom, a take-off on stuntman Evel Knievel, complete with handlebar mustache. Reeves really got into it, Cooley says—despite the character playing only a minor comic-relief role.

That performance represents quite a stylistic departure from Reeves’s other role this summer, in the violent, R-rated John Wick: Chapter 3—Parabellum. “Keanu came in to record his lines [while filming Parabellum], so I asked him how that was going,” Cooley recalls, launching into a perfect Reeves impersonation for the response: “‘Dude … yesterday I got to kill a guy with a book.’”

Legendary comedian Don Rickles had signed on to once again voice Mr. Potato Head, but he died before he could record his lines. Rather than recast the role, the filmmakers compiled his performance from hours of unused content Rickles previously recorded for the Toy Story properties, not just the movies but also theme parks, video games, and television specials.

Tony Hale of “Veep” joins as Forky, a MacGyver-like creation fashioned by Bonnie during a kindergarten class project. He consists of a spork with googly eyes, pipe cleaners for arms, and popsicle sticks for legs. It represents a notable minimalistic departure from the corporate mass-produced nature of all the other toys, memorably demonstrated during a scene from the second installment when Buzz Lightyear encounters thousands of his clones in a huge toy store’s Buzz Lightyear aisle.

Since the last installment in 2010, children’s playthings have become far less material and far more digital, contributing to last year’s bankruptcy of Toys R Us and the 2015 closure of toy store FAO Schwarz. “We went the exact opposite way of technology with Forky, didn’t we?” says Rivera, laughing. “Kids just being creative was something we observed from our own kids. My kids do have iPads, but they still love toys and play with dolls.”

The filmmakers originally wanted to name the character Sporky, but the word “spork” was trademarked. While they could use the word in dialogue, it couldn’t be a character’s name.

The more things change …

The story tackles several themes unexplored in previous installments. Forky struggles with feelings of worthlessness. “I am not a toy,” he laments. “I was made for soup, salad, maybe chili … and then the trash.” Woody deals with the possibility that what had always given his life purpose and happiness may have been limiting him the whole time. “Who needs a kid’s room when you can have all of this?” Bo Peep asks him when looking at a carnival. “Open your eyes, Woody. There’s plenty of kids out there.”

Yet some things never change. During the opening credits, a time-lapse sequence occurs to the tune of Randy Newman’s song “You’ve Got a Friend in Me,” the franchise’s musical theme, which has appeared in all three previous installments. Pixar’s trademark humor is still present too, including double entendres for the adults. At one point when frustrated, Woody exclaims, “Chutes and ladders!”—holding the opening sound of “chutes” for just a millisecond more than necessary.

Graphics

The animators truly outdid themselves on this project. A nighttime carnival scene contains more than 44,000 light bulbs. The base of a playground slide contains almost unnoticeable grains of sand, since children might go on the slide after leaving the sandbox. Spiderwebs dot corners of dusty buildings; one animator even designed a program of artificial intelligence “spiders” that could create their own spiderwebs, saving the animators the time of creating each individual strand themselves.

During an antiques store sequence, animators created more than 10,000 individual objects to place around the 3-D set. Though you’d almost certainly never notice it, the objects are arranged in distinct sections, just as in a real store: a pinball corner, a sewing area, a 1950s section. Squint and you’ll see several objects referencing previous Pixar films, including a gramophone with a vinyl record of the song “Remember Me” from Coco, or a parody of the painting Dogs Playing Poker featuring the canine Dug from Up.

Is this the end?

“Probably the most memorable time we had [during production] was that last recording session, which was Tom Hanks,” Nielsen remembers. “It was pretty special. That really landed on us. You just had to mark that moment. We all recognized—including Tom—at the end of that session, this could be the end of a character he’s been playing for over 20 years.”

But it’s not the end … not really. The three existing Toy Story films are among the few films from the past 20 years that we can say with certainty will still be watched by children many decades from now, just as vintage Disney classics Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Bambi still are. Perhaps Toy Story 4 will join their ranks.

But first, the filmmakers need to make sure they’ve saved a backup copy.

Share this post