2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of Boxoffice Pro. Though the publication you hold in your hands has had different owners, headquarters, and even names—it was founded in Kansas City by 18-year-old Ben Shlyen as The Reel Journal, then called Boxoffice in 1933, and more recently Boxoffice Pro—it has always remained committed to theatrical exhibition.

From the 1920s to the 2020s, Boxoffice Pro has always had one goal: to provide knowledge and insight to those who bring movies to the public. Radio, TV, home video, and streaming have all been perceived as threats to the theatrical exhibition industry over the years, but movie theaters are still here—and so are we.

We at Boxoffice Pro are devotees of the exhibition industry, so we couldn’t resist the excuse of a centennial to explore our archives. What we found was not just the story of a magazine, but the story of an industry—the debates, the innovations, the concerns, and above all the beloved movies. We’ll share our findings in our year-long series, A Century in Exhibition.

The studio system that thrived during Hollywood’s Golden Age died in the 1960s. Challenges in the form of pay TV, antitrust legislation, low admissions, and censorship had worn down the studios in the previous decade. But the 1960s brought a new challenge that proved too difficult to overcome: a society in turmoil.

Classic westerns, patriotic war movies, family musicals, and biblical epics were receiving an increasingly tepid reception at the box office. Unable to comprehend the tastes of their young audience during the time of the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and the growing counterculture, studios were ever more disconnected from their patrons. There was one question that veteran studio executives were no longer able to answer: What was an American film supposed to be? As studio films floundered and aging studio executives lost control of the industry, foreign and art house films filled the gap, influencing a generation of American filmmakers who ushered in the era of New Hollywood.

Until the 1960s, the industry had never truly confronted its own racism. In Boxoffice Pro, so-called Negro theaters were rarely mentioned. From the 1920s to the 1950s, the magazine published just one advertisement for a Black-led movie. One of the ways in which the exhibition community was forced to come to terms with the question of race in the 1960s was the desegregation of movie theaters.

Until the middle of the decade, most Southern cities practiced segregation in their movie theaters, either by segregating individual cinemas—with designated balconies for Black audiences—or by having separate cinemas for Black and white audiences. Black-only theaters, which were run by African American managers but often owned by whites, were less numerous than their white-only counterparts and mostly ran second- or third-run films. Some cities, like Charlotte and Chapel Hill, North Carolina, had no theaters for Black audiences at all.

As the civil rights movement progressed, picketing campaigns, mostly led by students in urban areas of the South, paved the way for the desegregation of movie theaters. Major circuits operated by Loew’s (later Loews), RKO, and Warner—although desegregated in the North—were targeted by protestors for policies in their Southern locations. Boxoffice Pro documented one of the largest student-led desegregation campaigns, which saw approximately 1,500 students march in Atlanta in February 1961. According to the magazine, most of Atlanta’s downtown movie houses began desegregating in May 1962 by permitting a small number of African Americans to attend each showing for a trial period of a handful of weeks, a strategy used by many Southern theaters before integrating completely.

In May 1963, Attorney General Robert Kennedy praised exhibitors for moving forward with voluntary integration when he invited influential exhibitors to the White House, seeking to persuade them to support President Johnson’s civil rights legislation. The idea was that voluntary desegregation of movie theaters, highly visible hubs in both Black and white communities, could spill over to other businesses. Boxoffice Pro founder and editor Ben Shlyen commented on the meeting: “From a humanistic, economic and political viewpoint, it is seen that the change called for must be made.” He added, however, that it could not “be done on a wholesale basis” due to the potential for violent outbreaks. “The threat of legislation to force integration is not the way to bring about the change called for by the times and conditions,” he argued. Overall, the matter of desegregation was not frequently discussed by the magazine’s writers. But the publication chose to publish a letter by a Southern movie manager in 1963, who wrote: “[The manager] hears it plenty when he might play a movie appealing mainly to children, such as a Walt Disney film. He gets calls from mothers wanting to know if his theater is integrated, and if it is, the mother will not send her child.”

Contrary to what Shlyen thought, legislation proved the only way to force compliance. The end of legal segregation came in July of 1964 with the Civil Rights Act, and the Congress of Racial Equity found that all theaters were abiding by the law that same month.

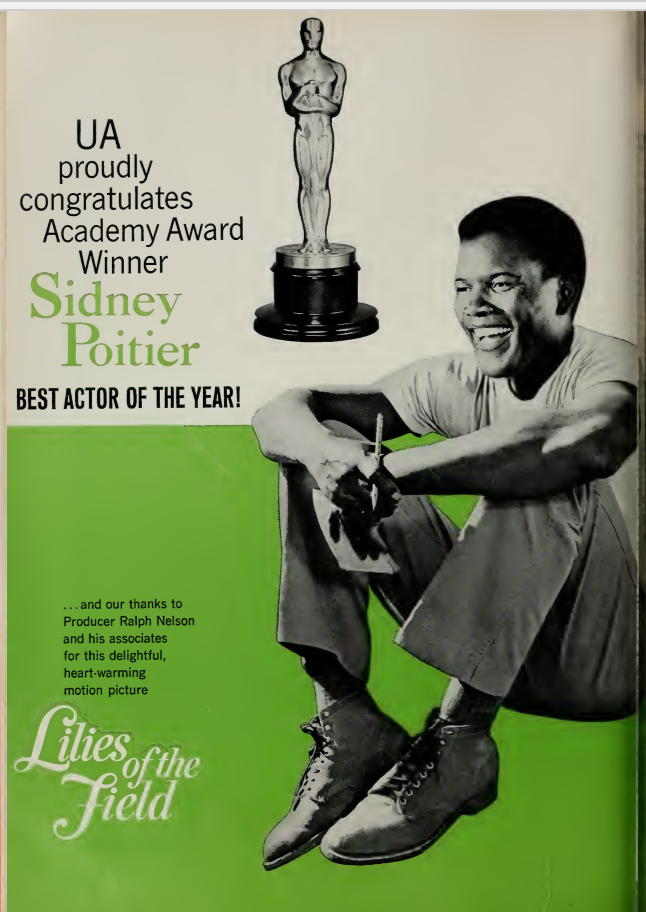

The civil rights movement also brought the (still ongoing) question of minority representation to the attention of Hollywood. The success of Sidney Poitier personified the controversy over the inclusion of African Americans both on and behind the screen. In 1964, Poitier became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in Lilies of the Field. Writes journalist and author Mark Harris in his book Pictures at a Revolution, Poitier was worried that his win would only lead to complacency, as the industry would busy itself with self-congratulation instead of working toward additional progress. Poitier’s fears proved correct: he did not get another offer for a year after winning the Academy Award.

But the actor was also internally conflicted over the kind of parts he was playing. Was portraying one-dimensional Black characters a necessary sacrifice to open the way for more actors of color in Hollywood? Some civil rights activists were indeed condemning the portrayal of African Americans on the silver screen. The NAACP led discussions with major studios to ensure progress on the issues of job access and on-screen representation. Other groups, including women and Latinx communities, began protesting as well. A 1962 Boxoffice Pro article reported that leaders of indigenous peoples in New Mexico had been “long frustrated over [their] treatment” in American film and were planning to open their own production companies. After the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a coalition of industry stars including Poitier, Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, and Candice Bergen created a nonprofit group to produce films on racial and social issues. The proceeds were to go to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Poitier became the top box office draw of 1967 with the interracial romantic comedy Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (which became Columbia’s biggest success to date), To Sir, With Love, and the Oscar-winning In the Heat of the Night. The success of these films proved two things: Black moviegoers could be a lucrative audience, and films about and starring Black people could play in the South. Exhibitors did not accept these truths without resistance. Some theaters edited moments, like Poitier and Katharine Houghton’s kiss in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, out of their prints. More alarmingly, the KKK picketed, and even considered planning attacks on, theaters that played these films.

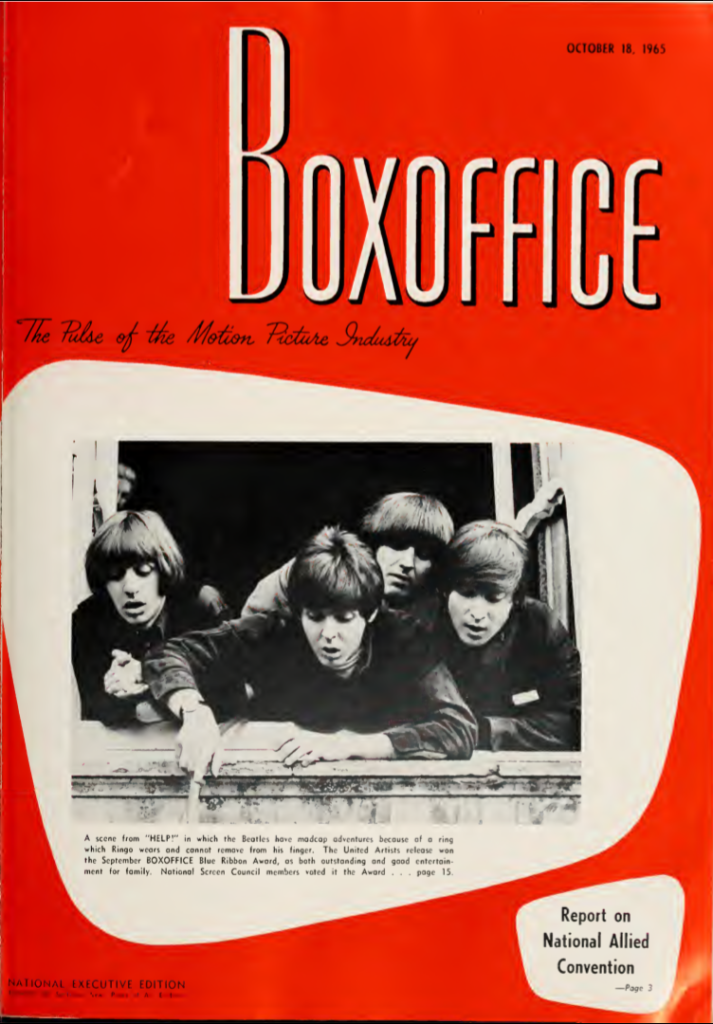

The new social context created by the civil rights movement and the counterculture revolution produced an appetite among younger audiences for films that spoke to the reality of the decade. The catastrophic flops of expensive films like Cleopatra (1963) and Doctor Dolittle (1967) proved the desire for something new. In 1952, the Supreme Court had ruled that Roberto Rossellini’s The Miracle, a controversial film that drew criticism from the Catholic Church, was an artistic work protected under the First Amendment. With that decision, the threat of government censorship was eliminated, opening the gates for a wave of foreign films that gave young moviegoers what they were looking for. These films defied taboos and censorship and embraced an experimental approach to filmmaking.. Among them were movies hailing from swinging London, which exported the Bond franchise and Beatles films—and stars like Sean Connery, Michael Caine, and Vanessa Redgrave—to North American audiences. The French New Wave introduced young urban intellectual audiences to Truffaut, Godard, Brigitte Bardot, and Alain Delon. Italian films propelled Antonioni, Fellini, Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni, and Gina Lollobrigida to fame.

The foreign craze was evident in the pages of Boxoffice Pro. Coverage of foreign film festivals boomed, as did editorial by foreign correspondents and columns like “Tokyo Report” and “London Report.” In fact, one anonymous writer reported in 1961 that 70 out of 176 pictures released by 10 companies in the U.S. between November 1960 and August 1961 were foreign. By February 1964, Twentieth-Century-Fox, MGM, Columbia, and United Artists were leading importers of foreign films. Smaller players like Embassy and Janus Films, which imported the work of Ingmar Bergman, steadily became more prominent.

It was the first time in Hollywood’s history that stars and films competed with their international counterparts. And Hollywood was scared. A writer summed up the situation in August 1961: “The foreign invasion appears to be creeping up on the American production industry and, in time, may equal it or surpass it. And from all indications, U.S. companies will increase their imports in the coming years. While the top pictures still come out of Hollywood, the quantity is diminishing.” The artistic merit of foreign films was often recognized in the magazine with positive reviews and the honor of Boxoffice Pro’s Blue Ribbon Award, but Shlyen always encouraged Hollywood to regain its dominant position.

Art house and specialty theaters thrived thanks to the influx of foreign films. Leonard Lightstone, executive vice president at Embassy, said in 1963 that specialty theaters were “mushrooming” and becoming more profitable as foreign films cut costs and became more flexible in their release strategies than first-run product. In 1960, Irving M. Levin, divisional director at San Francisco Theatres, attributed the proliferation of foreign films to their universal appeal and to “the inevitable maturing of film audiences as the country’s level of education and appreciation broadens.”

Independent cinemas, like the Bleecker Street Cinema in Greenwich Village, began showcasing international films. In April 1967, Shlyen urged exhibitors to “drop the notion that they must have ‘big box office product or nothing’” and give smaller films a chance. Shlyen’s plea came at a time of declining attendance and frequent closures of downtown movie houses as white audiences fled to the suburbs. Some also found, in foreign and art house films, the only way to fight TV. Independent filmmaker Leonard Hirschfield was reported saying in 1967, “Today the personal films are ‘most important’ because people can see the factory stuff on television.”

Foreign and art house films were catalysts for the end of censorship and the revision of the Production Code. Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, which featured full-frontal female nudity, did not receive the Production Code seal and was condemned by the National Legion of Decency. MGM distributed Blow-Up anyway through its shell company, Premier Productions. Grossing about $20 million, the film dealt a huge blow to puritanical attitudes. Foreign films had effectively created a double standard. As more theaters showed films without the Production Code seal, nudity became even more prevalent on-screen, raising questions about whether children and families were being driven away. But as the negative effects of censorship on creativity—not to mention the box office—became increasingly apparent, calls for an age-based classification system, which would give parents control over what their children could see, started to gain traction. In 1960, New York became the first state to establish the classification “Adult Only” for moviegoers above 18, sparking similar bills in other local legislatures.

Six years later, Jack Valenti became the third president of the MPAA. Valenti was preoccupied with censorship and the rising insurrection of Code-challenging filmmakers from the beginning of his tenure. In his first few weeks in office, he revised the Code to include the label “Suggested for Mature Audiences” on advertising posters. Shlyen welcomed the revision and praised Valenti’s “Herculean feat” for “giving the industry and the public a Code of Self-Regulation from which any benefits can be derived, not the least of which is the ‘better image that so much is spoken of and which can be the means for increasing attendance as well as to revive the custom of multitudes of lost patrons.”

But foreign films were no longer the only problem. A year before Valenti’s hiring, Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker was approved by the Code despite its nudity on the grounds of the “high quality” of the film. The decision created a loophole: Nudity was tolerable for “good” films, but not for ordinary ones. Mike Nichols’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which broke barriers with its strong language,finished what The Pawnbroker had started. The National Legion of Decency, supposedly influenced by Jacqueline Kennedy, gave the film an endorsement of “acceptable for adults with reservations.” Jack Warner released it in 1966 with a warning that the film was for adults only and provided individual contracts for theaters to sign, pledging that they would not admit any minors. Valenti was forced to approve the film with a “Suggested for Mature Audiences” label.

This became the first step toward the establishment of the new MPAA voluntary classification system, enacted in 1968. Movies were rated G (Suggested for general audiences), M (Suggested for mature audiences), R (Persons under 16 not admitted unless accompanied by an adult), or X (Persons under 16 not admitted). Valenti declared in Boxoffice Pro that “the creative filmmaker ought to be free to make movies for a variety of tastes and audiences, with a sensitive concern for children. That’s what this voluntary film rating plan does—assures freedom of the screen and at the same time gives full information to parents so that children are restricted from certain movies whose theme, content and treatment might be beyond their understanding.”

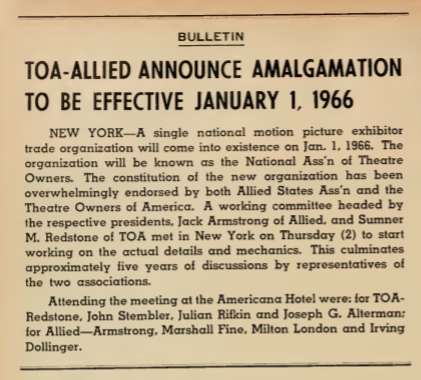

The MPAA and the International Film Importers and Distributors of America (IFIDA) were to monitor the ratings system with the newly formed National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO). After calling for a united exhibitor front for decades, Ben Shlyen’s wishes became reality with the birth of NATO on January 1, 1966. Boxoffice Pro followed its inception closely. In April 1964, the Allied States Association of Motion Picture Exhibitors and the Theatre Owners of America had agreed on a merger, talks for which had begun over a decade before. The challenges and changes of the 1960s brought an end to the ideological differences that had divided the two major exhibitor groups. In addition to enforcing ratings, in its early days NATO organized defenses against the industry’s greatest threats. It campaigned against the FCC for the regulation of pay TV, instituted a “movie month” with discounted prices, and pushed for more research on patron behavior.

The final nail in the coffin of the studio system came in 1967. That year, the Academy Award nominees were four films representing the new standard of antiestablishment, more inclusive filmmaking— Bonnie & Clyde, The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and In the Heat of the Night—as well as Fox flop Doctor Dolittle, a film that epitomized the studios’ disconnect from the current culture. The success of these new types of films was indisputable. Influenced by European New Wave cinema, young directors who had trained in theater and TV like Sidney Lumet, Arthur Penn, Mike Nichols, Sam Peckinpah, and John Frankenheimer were not afraid to take on taboo subjects and resist the status quo.

While indies like Easy Rider and The Wild Angels were thriving, the Big Five were collapsing. Walt Disney had died suddenly at 55 in 1965, Paramount was sold to Gulf and Western Industries in 1966, and Warner Bros. sold a third of its shares to Seven Arts in 1967. MGM was sold to a Nevada casino millionaire, Kirk Kerkorian, in 1969. Even United Artists and Columbia, which had been taking more risks with independent films, were shaken. United Artists became a subsidiary of an insurance company, Transamerica Corporation, and there were rumors about a French bank taking over Columbia. The only Old Hollywood mogul left was Darryl Zanuck, who remained at the head of Twentieth-Century-Fox. By the close of the decade, the golden age of studios had ended and New Hollywood was ascendant.

Share this post