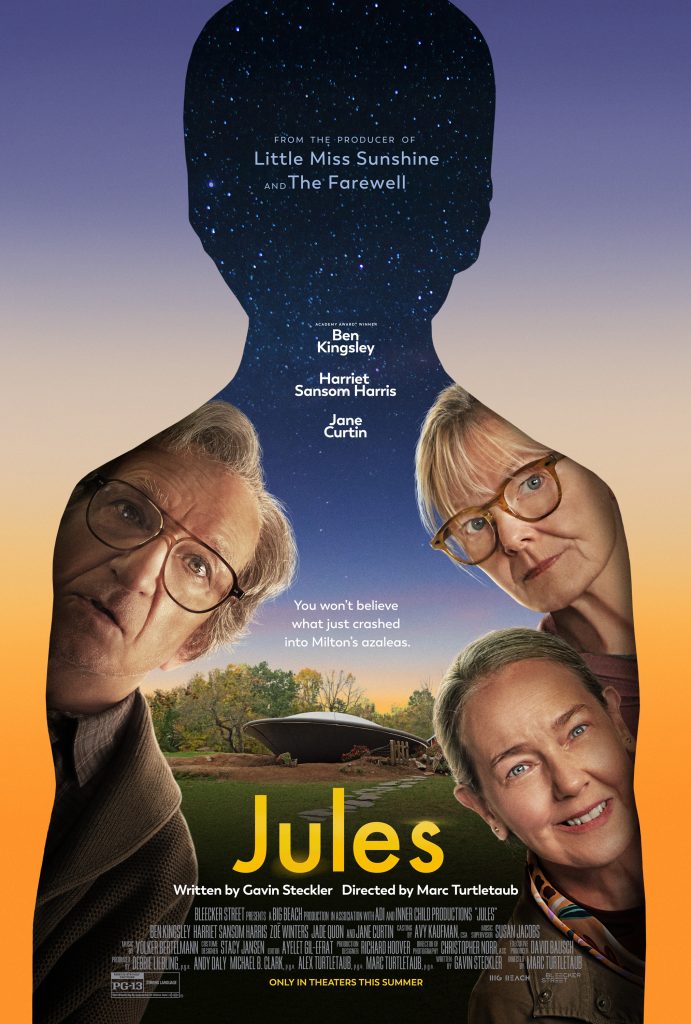

For twenty-five years, Marc Turtletaub has produced a long list of indie darlings—Little Miss Sunshine, Sunshine Cleaning, Loving, and The Farewell among them. His credits as a director include the big-hearted 2018 charmer Puzzle. In his latest film, Jules, the quiet lives of three civic-minded senior citizens in small-town Pennsylvania are reinvigorated by an experience of the extra-terrestrial variety. Prior to the film’s release, Boxoffice Pro spoke with director/producer Turtletaub on bringing independent features to big screen audiences and the responsibility of making meaningful movies. Encounter Jules this weekend, when the sci-fi dramady from Bleecker Street lands in theaters.

You’ve previously described yourself as a creative producer. How has your extensive producing career informed your work as a director?

Being around great directors through the years has given me an opportunity to see many different styles. You learn the technical things by observing, but there’s nothing like doing. It’s kind of like, ‘Okay, how am I going to be a great writer? I’ll read about writing.’ No, it doesn’t work that way. You just have to go do it. At the end of the day, it takes a while to find your own style; your style of working with actors, your style of production design, all of it. Some of it’s already there, the way you come in. You come in with a sense of style, or not, but then there’s the whole aspect of working with actors, which is probably the most important [aspect] that you develop on your own.

Speaking of actors, Jules brings together a lauded ensemble cast: Sir Ben Kingsley, Harriet Sansom Harris, and Jane Curtin, along with Zoë Winters and Jade Quon as Jules.

People give directors so much credit. When you have actors like Sir Ben Kingsley and Harriet Harris and Jane Curtin and Jade Quon, you just get out of their way. I don’t rehearse. After the actors have brought in what they’re going to bring in—without my mediating it, without my telling them what to do—there’s always an opportunity, after a take or two, to go in and say, ‘Hey, how about if we try something different?’ This is what I was talking about in terms of learning your own style. I learned that I did best when I didn’t rehearse with the actors.

The characters are coming to terms with the foreign, or shall we say alien, nature of aging. There is a fear of the unknown there.

The alien gives these old people what we all wish to have with our friends and our partners. You want that perfect listener. And Jules is that perfect listener. So there’s a parallel there. These three wonderful characters in the movie, who have really never been able to share their most intimate stories, find they’re able to when they have a perfect listener, and that enables them, in turn, to be able to talk to one another.

You dedicated your previous film Puzzle to your mother, and you’ve dedicated Jules to your father. There’s a lot within Jules that audiences are likely to identify with, regardless of their age.

I think it’s true. Whether it’s your parents, your grandparents, your friends, your spouse, we all begin to lose our faculties at some point. My dad began to lose his faculties, as we all will–and do–as we get older. That’s why I dedicated it to him, because it’s about living your life fully. Making deep friendships and finding meaning later in life, which we can do.

You’ve talked previously about championing stories that illuminate the human condition in a life-affirming or revealing way. Why is that important to you, and what does it take for stories such as Jules to make it to the big screen?

I think it’s really important. We spend so much energy, and time, and money on making these films, whether it’s our money, or in most cases, someone else’s money. We can do two things when we tell a story. We can entertain–above all else we have to entertain–but we can also touch people more deeply in some way. I always look for the two. It can’t just be pure entertainment. On the other hand, it can’t be something that’s didactic, [as in] ‘we’re just trying to teach something here’. It can’t be obvious. It can be as simple as in Little Miss Sunshine, ‘do what you love and forget the rest’. It can be as simple as that. In Jules, it’s about living your life fully, no matter what age you are, and finding connection later in life. We have the opportunity to do that, and I think we have a responsibility, frankly, as filmmakers to be able to touch people deeply and hopefully connect them. You can do that and still entertain.

Jules was filmed in your home state of New Jersey. Do you have a favorite moviegoing memory or theater that you frequented while growing up there?

You’re going to pull me back a lot of years. I don’t live in New Jersey now, although I have a great fondness for it. And I have relatives back in New Jersey. What I do remember, actually, is when I was young, independent movies were in New York, the few that there were. I remember going into New York, and most independent movies in those days were foreign films. I remember taking the bus into New York and going to watch foreign films and thinking, ‘Oh, that’s really what I want to do.’

Do you remember a specific film that really stuck with you or inspired you?

There were many. One that immediately pops into my head, is pretty much not like what I’m doing now [Laughs], but The Seventh Seal by [director Ingmar] Bergman. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, that’s possible. We can deal with really weighty subjects.’ Now, that’s maybe not the happiest of stories, but it was something that showed me how you could tell a myth in your stories, in the modern day. In a lot of ways, Jules is a myth. It’s grounded. It’s real. Those are real people having real issues, but it’s a myth at the same time, and I think that’s what The Seventh Seal was for me.

Myth really provides an entry point or a framework to look at the human condition and what that experience is like for all of us in one way or another.

That’s why we give children fairy tales. There’s a reason. You read Beatrix Potter, you read fairy tales, even the Grimm Brothers, you get something from them. The child gets something, maybe without even realizing what they’re getting. There’s always some sort of moral to it or some sort of message to it. I think that it’s because there’s a power of the imagination that’s stimulated when we’re not purely literal. When we’re metaphorical and dealing with myths, there’s something that goes in, in a deeper way.

Jules hits theaters this weekend. What are the challenges today for independent films that make it to the multiplex?

Independent films like Jules depend on word of mouth. We don’t have enormous advertising budgets. It’s so important to spread the word. [Bleecker Street] has been behind the movie and they’re opening it relatively wide, in real theaters, which means a lot. If you like the movie, please spread the word, because movies like this depend on word of mouth.

This is the type of film that really lends itself to the communal nature of cinema, where, ideally, multiple generations can experience the film together. What do you hope that experience will be like for audiences and what would you like them to take away?

Last night I did a screening in Queens. There were young people in the audience, a number of them, who enjoyed it as much as the older folks. And of course, the cast is older in this movie, but the issues and the humor are relatable to anyone. That’s part of why I loved it. You see most of these movies with older actors in it and they’re usually either on one end, completely frivolous, if I could use the word. And on the other end, they might be quite heavy and melancholic. This movie, while it touches your emotions, has wild fantasy and wild humor. That’s accessible, and I think enjoyable, to anyone of any age.

Share this post