French playwright Florian Zeller won critical praise for the feature-film adaptation of his own play, The Father, in 2020. It was a dream cinematic debut for the writer-director, who won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

The Father also delivered a Best Actor Oscar for its lead actor, Anthony Hopkins and nominations for Best Picture and Best Actress for Olivia Colman. Two years later, Zeller is back with the much-anticipated follow-up drama, The Son, from Sony Pictures Classics, opening in theaters on January 20. The all-star cast is led by Hugh Jackman, Laura Dern, and Vanessa Kirby—nominated for Best Actress the same year as Colman, for Pieces of a Woman. Hopkins himself appears in a one-scene role.

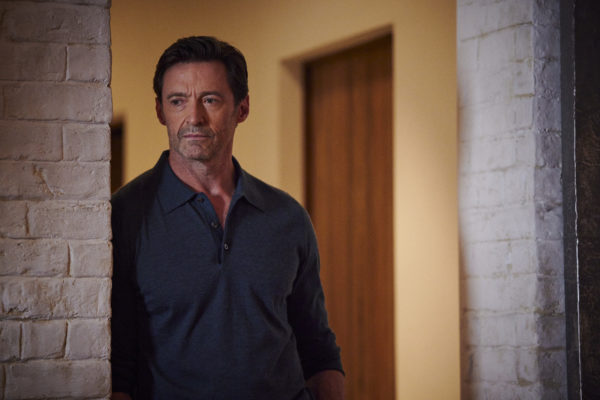

The film centers on Peter (Jackman), a wealthy New York lawyer who seems to have it all, from good looks to political influence. After divorcing Kate (Dern), he now lives in an expensive penthouse apartment with his much younger second wife, Beth (Kirby), with whom he has a new baby.

Everything changes when Peter’s clinically depressed and suicidal 17-year-old son Nicholas (newcomer Zen McGrath) moves in. The film doesn’t shy away from depicting the darkest aspects of a suicidal adolescent’s psyche and the effects on those in his close orbit, including scenes depicting cutting, self-harm, and a psychiatric ward.

Zeller spoke to Boxoffice Pro about nixing rehearsals for the film, directing Jackman’s dance moves, and his shifting opinions on concession stand snacks since moving to the U.S. a few months ago.

I was surprised to see Anthony Hopkins in this film. The Son is a prequel to The Father. Is he playing the same character?

It’s not the same character, it’s just the same actor. But to make a film is such an emotional experience. It was so powerful what we’d shared together with Anthony that we wanted to work with him again. Actually, he was the first one who read this script when I finished it. I sent it to him right away, and he called me back three hours later just to let me know that he’d already read it and wanted to do it. So he was the very first person involved in this project.

Almost everybody in this cast is non-American. Kirby and Hopkins are both British. Jackman and McGrath are both Australian. Did you consider setting this somewhere outside the United States, After all, The Father was set in London.

No, it was important for me to set this film in New York. In the first place, I wanted to shoot everything in New York and D.C., but we shot partly in London. I wanted to do this because I didn’t want to tell a British story or a French story or even an American story. I wanted to do something as universal as possible. New York is really the crossroads of the world. This kind of story could happen to anyone, anywhere. To do it in New York, for me, was a way to highlight this dimension.

You moved to the U.S. four months ago, after you’d already finished this film. Have you noticed anything about your new American life that makes you think, “I got that element of America wrong” or “I got that element right”?

A film is always kind of an abstract world. It’s not a documentary. Especially this one, where almost everything is set in an apartment. What was more important to me was to make sure it was realistic in terms of the way it shows the psychiatric world. It doesn’t work the same in France and the U.K. as in the U.S.

Later tonight, we have a screening with NAMI [National Alliance on Mental Illness]. It was important to me that they saw the film and supported the film, that in their experience it was very truthful to what they know. So it was important for me to make sure that it was truthful and connected to reality for the people who know.

You just mentioned that psychiatric patients are treated differently in Europe than in the U.S. How so? And how did that change the film, given its American setting?

It’s technical things. For example, a psychiatrist here can force a patient to stay, but he has to go through a judge. [That comes up as a major plot point in the film.] This is something that doesn’t exist in France. In France, you can take anyone out of the facility. You just have to sign a paper to take responsibility yourself, so you can’t sue anyone afterwards. In the U.K., you cannot make any decision against medical advice.

Jackman is a dancer, currently performing on Broadway in The Music Man. In the one scene in the film where we see him dancing, his moves are intentionally terrible. How did you direct him to dance so badly?

It’s true, he was supposed to have an embarrassing dance. But to have a bad dance on set, you have to be a very good dancer in real life. I remember the day we did that scene, he offered me several versions of his hip sway. He said that he tested them on his own daughter. She was like, “That’s perfect, Dad. You’re very embarrassing.” So he was comfortable about it.

That’s arguably the happiest scene in the film, yet there’s an undercurrent of melancholy. Peter, Nicholas, and Beth seem to make a collective emotional breakthrough together while doing absurd dance moves to the song It’s Not Unusual by Tom Jones. After a while, you slow the visuals down and sub in a more mournful song.

As a viewer, you feel like you’re not going in the right direction. That it’s not going to end well, even though the characters keep saying, “It’s going to be alright now, it’s going to be alright.” As Chekhov says, “When you have a gun in your story, you have to use it.”

Well, you have something of a literal Chekhov’s gun in this script. Peter has a weapon which he received as a gift many years prior, which he can’t bear to part with for sentimental reasons, even though he now has a suicidal teenage son in the home.

I didn’t want you to see the gun itself, but we hear that it’s hidden behind a washing machine. There are these washing machine shots. You can feel that there is a danger. The clothes are rolling, rolling, like a tragedy that you can’t stop. The feeling of the audience is that it’s not going in the right direction. You want to shake the characters and say, “Stop! Don’t say that, don’t do this.”

My point is that tragedy is preventable. That’s the whole point of the film. If the right words were used, if the right conversation was had. It’s difficult to accept that. So yes, tragedy is preventable.

You mentioned that you never show the actual physical gun. There are several things in this film that you don’t show. For example, when Nicholas talks about how much he hates it at the psychiatric ward, you never depict his actual experiences there. Or when Peter and Beth talk in the morning about how they’d had a fight the previous night, you don’t show the fight. Why did you take that approach?

It’s true that the script is built with a lot of ellipses. It’s a way to leave room for the audience to build the story by themselves, to be in an active position, to find their own way through the meaning. I feel that it’s always very rewarding, as a viewer, to create another scene behind a scene.

On a film like this, which is so serious and even morbid at times, is the atmosphere on set like that too? Or do you have any funny stories from the set?

It was not funny. It was intense, but it was very intimate. We shot in the middle of Covid, so we didn’t have dinner with anyone else outside of the set. So it was just a few of us in a room, all the time, for eight weeks. I felt that everyone involved in this film had a real and clear reason why they wanted to make that film, so they were very focused.

Also, the process of the shooting itself was special. We made a decision not to rehearse at all. I come from the theater, where there’s a lot of rehearsing. Hugh comes from theater and loves rehearsing. But I made the decision from the very beginning not to rehearse.

It had to do with the way I met Hugh. He was the one who approached me in the first place. I was working on the adaptation. He heard about that, he knew the play, he’d seen The Father. He wrote to me. One day, I received a letter. He said, “If you’re already in conversation with another actor, please forgive my letter. But if you’re not, I would love to have 10 minutes just to let you know why I should be the one to make that film.” I was very surprised to receive this letter, of course, for its honesty, its courage, and its humility.

So we met on Zoom. It was just a regular meeting. I was not planning to make any [casting] decisions. It was just a first conversation. But after a few minutes, I stopped the conversation and offered him the role, because I felt strongly that he knew what it was about. He was not only attracted to it as an actor, for the challenge, but also as a man and as a father. He was deeply connected to these emotions.

So I thought it was important for us to explore these emotions in a very authentic way, without faking anything, without trying to perform for the sake of performing. I made that decision because I felt that, in a way, he was the character. It was a way to allow him to be himself in front of the camera. And because he’s a dancer, he’s so technical; he has the ability to control everything. It was about trying to let it go, you know?

Also, this is a story about a character who’s trying to fix everything but somehow is losing control of the situation. So it was a way to put Hugh in this position where he’s losing control of the situation on set. Rehearsals are about control and questioning everything. So I suggested we do no rehearsal, just to be himself with no protection. Just deal with the emotions that could appear in the moment, in the now, that we were exploring together on set.

Did anything about the finished film come out differently due to the lack of rehearsals?

It was very interesting and created some opportunities, in terms of process. For example, in the first scene of the movie, we see Kate knocking at the door to speak with her ex-husband Peter about Nicholas. But this is not the first scene we shot. We started by shooting all the scenes in the apartment between Beth and Peter. So after a few days, we were very familiar with the space. Laura was not welcome on set, she was not allowed to come join us, so she knew nothing about the set. I asked her not to meet Vanessa until the first take of the film.

So when she knocks at the door and the door opens, the camera’s on her, this is the very first time she sees Beth. This is the first time she has a sense of her ex-husband’s new life. She has to deal with all this information at the same time. Spending so many hours in the editing room, I can tell, all the complexity of her emotions at that moment are connected to the fact that she has to deal with so many emotions and information at the same time. We feel she’s not completely confident being in this space, that she’s not welcome.

This is something that could not have been done if we were rehearsing.

Or there is a moment when there is a gunshot. It’s kind of hard to [rehearse] the terror that should happen at that moment. When [the actors] came, I told them it would be just a rehearsal for the camera, there would be no gunshot at the end of the sequence. I asked them to just do the lines, even though I knew [the gunshot] would happen.

So they did it and they were not expecting anything. Suddenly, it happened. The surprise and the terror is real. The body language, the emotion, everything was unplanned. To work with actors, sometimes you need a strategy to make things happen. It was only one take, and this is the take which is in the film.

I believe you have a teenage son, like the teenage son Nicholas in the film?

Yeah, I have two children. One is 24 and one is 14.

The 14-year-old is a somewhat similar age to Nicholas, who’s 17. Has he seen the film?

No. He wants to see it, so I think he will. But it’s a story that comes from a personal place. I had a first son that went through difficult moments, so it was coming from this experience. [My 14-year-old] knows things about that story.

But you’re not making something just to share your own story; it’s more about sharing emotions that you feel could be relevant to others. Because it was first a play, I realized when it was onstage in London and Paris, there was something special. The response of the audience was very powerful and impressive to me. They were waiting for us after every performance, not to say congratulations, but to tell their own story, to share their own story. There were conversations: “I know what you’re talking about, because my nephew, because my uncle, because my daughter,” etc.

I realized that so many people know a lot about these mental health issues. So many people, as parents, know what it is to be in a position where you don’t know what to do anymore. So many people are in pain out there. And also, so much shame and so much guilt and so much ignorance that I really wanted to open a conversation. That’s why we wanted to make this film.

Do you feel that goal is increased by releasing the film in cinemas, with its shared communal experience, instead of releasing it first on streaming where you’re probably watching it alone?

When you’re going through a difficult situation in your own life, you always feel like you are by yourself, alone. I think this is what art, and especially cinema, can provide: the feeling that we are all in the same boat. Experiencing it in real life, with other people, makes it even more obvious that we are all part of something bigger than ourselves, which is humanity.

There is a consolation to remembering that we are not alone, especially what it comes to these kinds of topics. As soon as you understand that we are not alone, you can ask for help. You have to admit that some people know more than you do. And you can save a life.

So I think that’s the joy of sharing. I’m talking about “joy” even though it’s a hard film. But even a hard film can be tender. I strongly believe in the cathartic power of cinema—even when it’s hard.

AT THE MOVIES

What was your hometown cinema growing up?

I come from Paris. I’m French, as you can hear. [Laughs.] It was on the Champs-Élysées, which is the main street in Paris. This is where I used to go.

Do you have a favorite moviegoing memory or experience from that theater?

The film that I remember, that really made me discover the power of cinema, was an American movie: Rain Man. I was eight, nine, something like that. At that moment, my life was kind of similar to what happened in that story. I had a big brother who was in difficulty, but nobody was explaining to me what was going on. I had a lot of anxiety about that. Suddenly, through cinema, I understood my own life in a different way. I understood the power of cinema, which is to put your own life in a different light, and to be slightly in relief from some anxieties.

From that moment on, I started being obsessed with Tom Cruise, the American landscape, and Hans Zimmer. The fact that I’m working with Hans Zimmer on this film, there’s a connection with that first feeling of being impressed with the power of a movie.

What’s your favorite snack at the movie theater concession stand?

I never eat anything in a cinema. Never. I’m French, and in France, it’s very rare that you can eat or drink something in a cinema. It’s not part of our habits. But now I live in L.A. I moved there four months ago. My children are already used to buying snacks and sodas. I understand the joy of it. But it’s a lot of sugar.

Share this post