2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of Boxoffice Pro. Though the publication you hold in your hands has had different owners, headquarters, and even names—it was founded in Kansas City by 18-year-old Ben Shlyen as The Reel Journal, then called Boxoffice in 1933 and, more recently, Boxoffice Pro—it has always remained committed to theatrical exhibition.

From the 1920s to the 2020s, Boxoffice Pro has always had one goal: to provide knowledge and insight to those who bring movies to the public. Radio, TV, home video, and streaming have all been perceived as threats to the theatrical exhibition industry over the years, but movie theaters are still here—and so are we.

We at Boxoffice Pro are devotees of the exhibition industry, so we couldn’t resist the excuse of a centennial to explore our archives. What we found was not just the story of a magazine, but the story of an industry—the debates, the innovations, the concerns, and above all the beloved movies. We’ll share our findings in our year-long series, “A Century in Exhibition.”

We start the series with the 1920s, specifically 1925, which is when reporting on this newfangled thing called “synchronized sound” began to appear. Also affecting the industry in the roaring ’20s—and written about extensively in the pages of The Reel Journal and its companion regional publications—were a construction boom and consolidation. All three of these things—consolidation, adoption of new-fangled amenities, and the development of new technology—reverberate through the years and continue to affect our industry to this day.

Talking Pictures Are Here to Stay

No technological innovation has shaken the industry like the introduction of sound. When Western Electric and Warner Bros. developed the Vitaphone, the first successful sound-on-disc technology, in 1926, it forever changed the way movies are made.

The first-ever mention of sound in the pages of Boxoffice Pro, then called The Reel Journal, was in August 1926 with the world premiere of John Barrymore’s Don Juan. The Warner Bros. drama became the first publicly shown “talkie,” with prerecorded sound effects replacing the live music (orchestra or organ) that had accompanied most major releases up to that point. Nearly half the premiere was devoted to explaining the intricacies of the Vitaphone to the fascinated, if somewhat skeptical, audience.

As similar technologies for synchronizing sound and image, like Fox’s Movietone, stormed the market, there was a “talkie frenzy” that led to skyrocketing film production and attendance.

The Boxoffice Pro archives provide an interesting glimpse into how the transition to sound was viewed as it was happening. We see the optimism and enthusiasm of the early days as well as the uncertainty. Are talkies here to stay or just a phase? Will the production requirements of sound degrade the quality of films? How will censorship adapt to an increase in dialogue?

But no other debate captivated exhibitors more than the one discussed in owner/editor Ben Shlyen’s article on November 10, 1928, below: How will smaller exhibitors who can’t afford to install sound equipment be impacted? Shlyen understood that, in time, as costs decreased, smaller exhibitors would also reap the benefits of sound. Until then, he believed that their success depended on quality silent features and above all on the “right kind of showmanship.”

As one of our writers observed, “The motion picture was reborn again in 1928. The infant industry learned to talk.” With an announcement in November by the Electrical Research Laboratories and Western Electric allowing producers to choose different companies to record and project sound, the popularity of talkies exploded further. Paramount became the first studio to drop the production of silent films entirely, followed by Fox in March 1929. Talkies were here to stay.

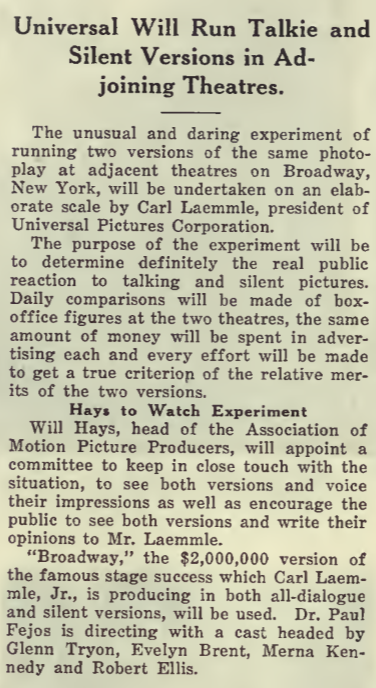

Amid the talkie boom, Joseph Schenck, president of United Artists, warned against a blind belief that talkies would obliterate silent pictures. “It is important to remember that the picture is still the foundation of screen entertainment and sound only an accessory,” he proclaimed. He was also afraid that dialogue would ruin the international appeal of American pictures. History would prove him wrong twice. But Schenck was not the only one to raise questions about the durability of talkies. Sam Sax, president of Gotham Productions, wrote that “the picture made the motion picture theater popular,” while sound was transitory and an accessory at best. In March 1929, a questionnaire asked exhibitors if silent films were still considered a good bet at the box office. The results were an overwhelming yes.

The sheer cost of installing sound equipment and buying prints of talkies left most small exhibitors outside the initial wave of sound hype. More and more articles, especially after 1929, denounced how the move to sound disproportionately benefited either movie palaces or theaters that were producer-owned or located in major markets. Sometimes producers offered two versions of their films, one with sound and one without, but exhibitors often complained about the bad quality of the latter and preferred to only buy original silent features. By August 1929, a Boxoffice Pro survey showed that 25 percent of all theaters were wired for sound and that those theaters captured 75 percent of all revenue. An estimated $1 million was invested in equipping theaters with sound by the end of the decade.

The Theater Construction Boom

After World War I, feature films consolidated their position as the most popular form of mass entertainment, eclipsing vaudeville houses and nickelodeons. With this came an explosion in movie theater construction. In 1925 alone, according to our archives, some 15,000 theaters were built, more than in any other year up to that point.

This was a period of business innovation. Powerful regional chains such as Loew’s (later Loews), which started in New York City as a vaudeville company; the Pennsylvania-based Stanley Company of America; and, biggest of all, Chicago’s Balaban & Katz used innovations from the retail world, copying the likes of Kroger and A&P, to create a “scientific form of management,” enabling them to capture vast swaths of regional markets.

Throughout the 1920s, Associated Publications, the corporate entity formed by Shlyen in 1925 to group The Reel Journal with other regional publications that he had acquired, chronicled that boom. Multiple issues of the various Associated Publications magazines featured detailed profiles on the construction of new movie houses and movie palaces. A dedicated section, Kino Equipment, provided exhibitors with tips on all things equipment. Meanwhile, ads presented exhibitors with their choice of lighting fixtures, chairs, marquees and, of course, projectors.

This decade was one of profound architectural changes. It saw the birth of what would subsequently be regarded as a moviegoing necessity: the air-conditioned theater. The first of these was built in 1922. Countless ads promoting the best A.C. system followed.

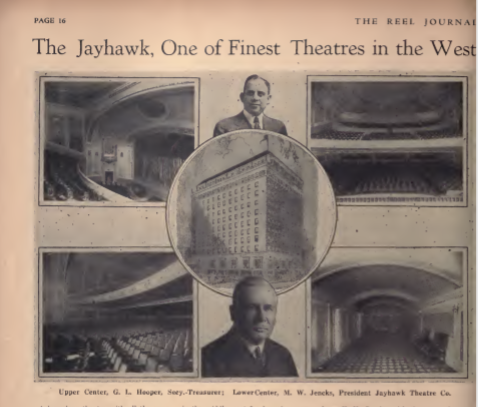

The late ’20s also saw a peak in the construction of movie palaces, hundreds of which opened their doors during this time. Meant to attract the upper class, which scorned regular theaters in favor of luxurious vaudeville houses and traditional stage theaters, movie palaces were designed to make their audiences feel like royalty. Mostly built in city centers, these “de luxe” theaters boasted extravagant architecture, stage shows, and orchestras in addition to first-run films.

Shlyen, while not against improvements in a general sense, opposed this “theater orgy.” He saw this construction boom as vanity that did not serve a practical purpose. “One is attempting to outdo the other, not by clear reasoning, not by practical purpose, but by seeing how much more money he can spend than the other,” he proclaimed. Once again, Shlyen had the fate of the small exhibitor in mind. How could independent exhibitors remain in business when newer, bigger, and better movie houses took over their towns?

Regional chains grew throughout the first half of the decade, after which studios began to engage in more monopolistic behavior. In 1925, the largest theater chain, Balaban & Katz, was acquired by Hollywood’s largest studio, Famous Players-Lasky. In April of that same year, Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures announced its acquisition of the Hostettler Circuit, an important Kansas City player. And so the race to acquire movie theaters began.

Even in 1925, Associated Publications foresaw the risks this posed for the industry. In an article on that May’s Motion Picture Theatres of America convention, Shlyen proclaimed, “If this industry is to grow and prosper, a safety valve must be maintained. The co-operation pledged by the exhibitors and the independents for one another can keep down the monopoly.”

Things didn’t happen quite that smoothly. The “majors” kept buying theaters, unabated. In 1928, Warner Bros. purchased the Skouras Bros. operation—which dominated the Kansas area with four first-run Koplar theaters, the First National franchise, the local Educational Branch, and the St. Louis Film Exchange—and theaters owned by the Stanley Company in Pennsylvania. In 1929, Fox’s acquisitions essentially eliminated independents in the greater New York area. The same year, RKO formed an alliance with Famous Players Canadian while seeking to expand its theater ownership by acquiring 14 Pantages houses.

Now small theaters weren’t just suffering from the high cost of the transition to sound and the pressure to keep up with regional chains through pricey architectural innovations; they also had to face the prospect of being acquired or put out of business because of the monopolistic behavior of the film studios.

Another threat to exhibitors was the practice of block booking, under which studios would force theaters, especially independents, to buy their films in “blocks”; if they wanted that weekend’s big earner, they would have to take several other, less desirable, films as well.

The twin issues of consolidation and block booking caught the attention of the U.S. Department of Justice. The first antitrust investigation was launched as far back as 1921, when Famous Players-Lasky was charged by the Federal Trade Commission for block booking. In April 1928, the Department of Justice filed two antitrust cases against 10 studios—Paramount, Famous Players-Lasky, First National, MGM, Universal Film Exchange, Fox Film, Pathé Exchange, FBO, Vitagraph, and Educational Film Exchanges—for monopolizing more than 95 percent of domestic distribution. A year later, nine of those studios were also indicted for violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Legal battles went on for more than two decades before studios were ordered to divest their theaters.

Needless to say, the issues of block booking and consolidation were discussed in practically every issue of the magazine, continuing to make headlines well into the 1940s. Shlyen initially expressed confidence that independent exhibitors were going to be just fine. He believed that studios would not acquire small, independent theaters outside major markets. His position soon changed, and after 1926 he began denouncing the behavior of the studios. At the same time, he believed that exhibitors could stave off obsolescence through innovation. In December 1926, Shlyen wrote, “This so-called menace may prove a boon to many exhibitors who have failed to heed duty by neglecting to build up their business, improve their service, and otherwise cater to public demands. But the awakening is here. The future of the independent exhibitor’s future lies in his own hands.”

Share this post