2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of Boxoffice Pro. Though the publication you hold in your hands has had different owners, headquarters, and even names—it was founded in Kansas City by 18-year-old Ben Shlyen as The Reel Journal, then called Boxoffice in 1933, and more recently Boxoffice Pro—it has always remained committed to theatrical exhibition.

From the 1920s to the 2020s, Boxoffice Pro has always had one goal: to provide knowledge and insight to those who bring movies to the public. Radio, TV, home video, and streaming have all been perceived as threats to the theatrical exhibition industry over the years, but movie theaters are still here—and so are we.

We at Boxoffice Pro are devotees of the exhibition industry, so we couldn’t resist the excuse of a centennial to explore our archives. What we found was not just the story of a magazine, but the story of an industry—the debates, the innovations, the concerns, and above all the beloved movies. We’ll share our findings in our year-long series, A Century in Exhibition.

In the 1950s, the theatrical industry saw studios, vendors, and exhibitors all reveling in a new wave of technological innovations. This time, the focus was on making the theatrical experience bigger and more spectacular—the better to compete with a little thing called TV.

The motion picture industry faced its first existential threat in the 1950s. Following the introduction of the Paramount decrees and the weakening of the studio system, exhibitors faced a shortage of product and declining admissions, and the industry met its most daunting competitor yet: television.

The pages of Boxoffice Pro reflected this turmoil. Despite a fast-growing U.S. population and exploding consumer economy, attendance was not increasing … or at least it wasn’t increasing fast enough, especially in the second part of the decade. In February 1955, editor Ben Shlyen explained the conundrum: “While the gross business is up, due to the partial elimination of the excise tax and higher admission prices, our attendance has not been increased.” In May 1956, a survey by Slindlinger & Co. found that American theaters lost 16 million patrons in the first week of the month because of an insufficient variety of pictures, a lack of effective advertisement, and TV.

Filling empty seats became a recurring mission for Boxoffice Pro and its contributors. Different solutions were routinely proposed: more blockbusters, higher ticket prices, discounts, extended runs, family nights. Shlyen urged more diversity in films as well as a different release strategy. In May 1956, he argued that fewer second-run theaters per neighborhood had resulted in a situation where most, if not all, theaters played the same movie for multiple weeks without sufficient alternatives for patrons who had already seen it. “Could it be that this—and not television, much as it has been credited—is the main cause of the wholesale closing of neighborhood theaters?” he pondered. Others called for a more social solution, like instilling moviegoing as a habit for younger generations and encouraging “the women of America” to bring their families to the movies.

Many contributors turned to the past to calm the “industryites.” Abram F. Myers, chairman of the board and general counsel of Allied States Association of Motion Picture Exhibitors, wrote that the motion picture industry has “survived the vicissitudes of the centuries because it satisfies a deep-seated craving of the gregarious human race for amusement and relation, not alone but in the company of others. So long as there are men, there will be theaters—television or no television.” In the same issue, a veteran exhibitor sought to reassure readers by harking back to how the industry had overcome the threat of radio: “It was a costly, discouraging and prolonged process. Some thought it could never be accomplished, but it was. New and improved methods of presentation turned the tide.”

The industry was facing crises on multiple fronts. Starting in the late 1940s, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had been hunting down suspected Communists in Hollywood. In addition to the bad publicity, there were financial costs: A report by Allied States Association of Motion Picture Exhibitors, one of the two major exhibitor groups, estimated that film companies had spent more than $1 million in settling contracts with ousted Communists. After the second HUAC hearings, about 212 individuals were blacklisted, among them prominent talents like Dalton Trumbo, who was eventually reinstated in 1960.

Boxoffice Pro reported that director Elia Kazan, who agreed to talk to HUAC to avoid the blacklist, repudiated his youthful ties to the Communist Party, explaining that “the Communists automatically violated the daily practices of democracy and attempted to control thought and to suppress personal opinion” (April 1952). Boxoffice Pro deplored the maltreatment of many industry players

and feared that the hearings “would besmirch an entire industry for the acts of a few who have a remote connection to [Communism]” (March 1951). The magazine subsequently ran multiple reports on the lack of influence of “Reds” on Hollywood films and emphasized the cooperation of industry leaders. The Red Scare started to subside in 1959 when the Academy announced it would repeal the rule on the ineligibility of Communists.

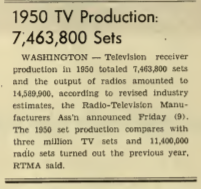

But the biggest crisis of the decade was undoubtedly the rise of TV. Talks about the medium dated back to the 1920s, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that TV became a practical form of entertainment. Indeed, the decade began with reports on the unprecedented manufacture of TV sets. In January, a record 7,463,800 sets rolled off the assembly line. For theaters, this meant competition for audiences—especially after color TV was introduced—and for product.

In January 1951, the first pay-per-view system, dubbed “Phonovision,” was tested in 300 Chicago households by the Zenith Radio Corporation. Viewers could send a phone signal to decode a movie for one dollar. Fearing that first-run films would go straight to TV, the exhibition industry strongly protested this new system. Exhibitors, sometimes backed by free TV networks, fought to ban pay-TV by pressuring the Department of Justice and the FCC. The stakes were immense. In a March 1955 editorial, Shlyen called for others to join the exhibitors’ “crucial fight for existence.”

In October 1954, Disney—partnering with ABC—became the first major Hollywood studio to create TV programming. Walt Disney believed it to be an exciting development for both industries. In 1955, studios opened their libraries for TV rentals and sales of films prior to 1948. RKO was the first, followed by Columbia (which sold features through its TV subsidiary Screen Gems), Paramount, and Fox. Starting with RKO in April 1956, some majors developed their own TV divisions, expanding their lots to handle the new activity. Studios also began buying stakes in TV. One of those was Paramount, which in 1951 acquired interests in pay-TV player International Telemeter Corp. Washington, D.C., took notice. In 1958, the government filed a civil antitrust suit against Universal Pictures, Columbia, and Screen Gems for fixing prices and eliminating competition.

Boxoffice Pro fervently warned about the myriad dangers of TV and urged studios to think of exhibitors. Shlyen also cautioned readers of the risks of complacency. In January 1957, he proposed measures like cheaper parking, babysitting services, and family nights. “We can beat television—or any other competition—if we get on the ball!”

But TV had a bright side. It offered new marketing opportunities, for one. In addition, some exhibitors were quick to embrace the potential of “telecasting” sports via cable TV. In 1950, Allied Association gave its full backing to the National Exhibitors Theatre Television Committee to continue the practice. That same year, Fox announced it would test the technology on a 20-theater network, leading to an uptick in interest for other major circuits. The first cable TV theater opened in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1956 to great success. Yet content providers did not always approve this expansion, and the cost of installation (estimated at more than $274.5 million in 1957) proved too expensive to make it a viable option.

Facing these crises, the industry found ways to adapt to the increasingly modernizing world. For Boxoffice Pro, one last moviegoing bastion was the drive-in. The “airers,” as these theaters were called, were not always welcomed by the rest of the industry. In fact, many indoor exhibitors lobbied to prevent future owners from obtaining zoning and construction permits and even managed to get a total construction ban in some areas. The truth was that drive-ins, entering their heyday in 1950, were already getting one-eighth of the industry’s total patronage. Boxoffice Pro rejoiced over this boom and the ingenuity of some drive-in exhibitors. For example, one drive-in in Minneapolis incentivized attendance by bringing in non-auto owners on a big bus. The magazine ran many ads for drive-in-specific equipment, including screens, speakers, and seats. Columns in our Modern Theater section gave advice for better drive-in showmanship.

But the real “savior” of the industry was the introduction of 3-D, wide screens, and stereophonic sound technologies. Cinerama Corp. showed distribution executives its innovative curved-screen technology for the first time on May 6, 1950, after 13 years of development. It featured a projection apparatus that could show movies eight times the size of a normal screen, four times the width, and twice the height. Ben Shlyen praised its “breathtaking” effect.

There were rapid technical advancements on the 3-D front, as well. In 1951, the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers hailed the technology as the “most promising theater entertainment of the future.” A year later, United Artists’ Bwana Devil became the first 3-D feature film, with great box office response.

The high-tech turning point took place in 1953. As major companies equipped more and more theaters with innovative new technologies, Boxoffice Pro spoke of a “third-dimension race.” Paramount was using its own 3-D solution. MGM, Columbia, and Warner Bros. turned to a system called Natural Vision, while 20th Century Fox used a French system with stereophonic sound called Anamorphosis.

These enhancements to the traditional theatrical experience popped up at an unprecedented pace, with everyone trying to bring something ever-more innovative to the table. For example, the Ohio-based company Tri-Dem claimed it had created a 3-D mechanism requiring neither a special screen nor glasses. On the exhibitor side, Chicago-based B&K announced the introduction of its own “Magnascreen” in January 1951. A Boxoffice Pro survey published in December 1953 revealed that more than 50 percent of indoor exhibitors had installed or planned to install 3-D and wide-screen equipment within the year. On the more gimmicky side were Smellorama, introduced in 1953, and Smell-O-Vision, introduced in 1959.

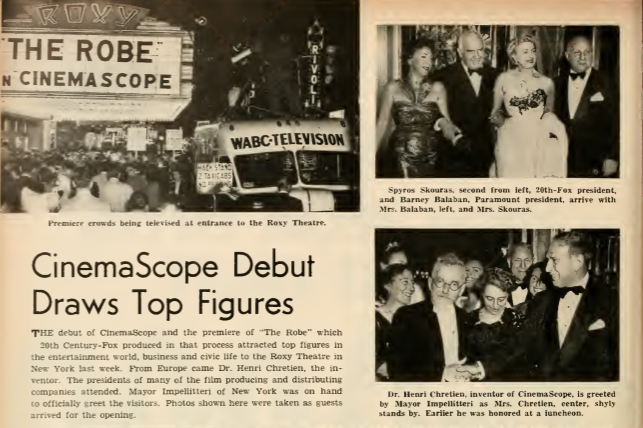

1953 was a landmark year due to the introduction of widescreen shooting format CinemaScope, first used with 20th Century Fox’s The Robe. Shlyen called the first public presentation of The Robe in September 1953 an “epochal event.” The premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theater was “one of the more spectacular in recent film colony annals.” Noting its immense success with the public, he observed, “It seems certain that the era of widescreen has not only begun; it is here to stay.”

In the months to come, CinemaScope was presented as a true “industry revolution.” Many filmmakers also saw its creative potential. Combining wide screens with advancements in Technicolor processes, filmmakers flooded the market with historical epics like Quo Vadis, Ben-Hur, Salome, and David and Bathsheba. In February 1953, Cecil B. DeMille explained that he had deferred filming the Ten Commandments to study 3-D, noting, “I am lucky that third-dimension appeared when it did and that it didn’t find me in the throes of production.” Other filmmakers were more skeptical. In August 1953, we reported that director John Huston was worried “about properly framing his stories on the horizontal screen and didn’t think the sacrifice was worth the effort.”

While Boxoffice Pro welcomed these innovations as beneficial to the industry, our writers also expressed caution, showing concern for smaller theaters just as they had following the advent of sound. Siding with Allied States Association of Motion Picture Exhibitors, Boxoffice Pro favored standardization as well as an industry-wide research program for improvements. Indeed, many smaller exhibitors failed to join the technological revolution of the 1950s because of the high costs of installation. In an attempt to counter those costs, Spyros Skouras, president of 20th Century-Fox, announced in 1953 that his company would extend credit to any theater that was unable to buy the equipment.

These innovations did boost attendance, but the recovery of the exhibition industry was not as spectacular as expected. As a result, industry leaders began to look for overlooked audiences. One segment was particularly lucrative: teenagers. A study published in December 1956 found that the teenage market

consisted of 16 million boys and girls—potentially making them the biggest moviegoer demographic—with a combined $9 billion to spend per year. Young people were also deemed less likely than their older counterparts to stay home and watch TV. A desire to attract teenage patrons (despite exhibitors’ fears of their rowdiness) brought new faces to films. Movies like Rebel without a Cause and Teenage Rebel as well as films starring Elvis Presley became hits. MPAA president Eric Johnston expressed his optimism in 1957 about the power of young people to save the industry: “There will always be motion picture theaters because ‘young people’ don’t want to sit at home and hold hands in front of their parents.”

Share this post