“We don’t sell tickets to movies; we sell tickets to theaters” notes film historian and critic Leonard Maltin as he quotes famous showman Marcus Loew. April Wright’s documentary Going Attractions: The Definitive Story of the Movie Palace tells the story of these theaters.

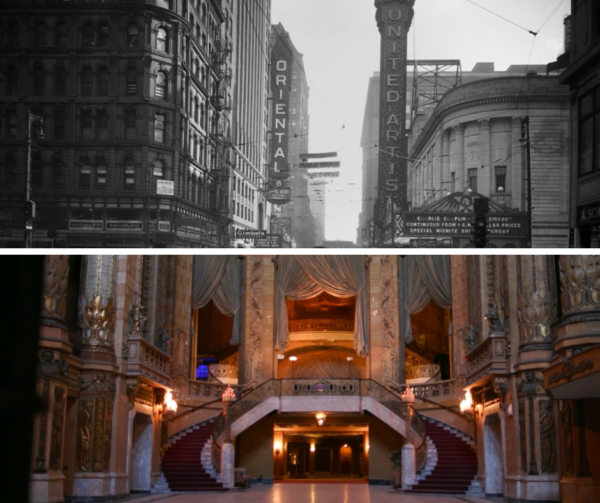

After chronicling the rise and fall of American drive-ins, the second installment of her Going Attractions series explores the origins of lavish movie palaces and documents the fight to save these cultural landmarks that are today facing extinction. Visiting more than forty historic movie palaces across the nation, Wright builds upon a rich photo archive with interviews of movie palace owners, film and exhibition historians such as Leonard Maltin, and passionate preservation activists.

With a nostalgia that urges action, we travel back in time to the boom of movie palaces in the 1910s until the Great Depression; their crisis with the arrival of TV, suburbanization and the multiplex; their resurrection as performing arts centers, classic movie venues, and even churches.

Boxoffice Pro chatted with director April Wright about her documentary, which opens in L.A. on October 24th, followed by a limited release across the country—in theaters and, of course, movie palaces.

Can you tell us about the origins of this project?

I had a cinephile family. My dad had an 8mm camera, and we had a projector at home to watch movies. My parents were very into movies. We would talk about what made them good and things like that. I grew up being very aware of movies, going to the movies a lot. We had a neighborhood movie palace down the street that my brother and sister worked at. It had a big single screen and a cool marquee. They tore it down when I was a kid, and I was like, “What are you doing?”

I also went to drive-in movie theaters growing up. They had three of them in the area. I made a first documentary about drive-in movies, Going Attractions: The Definitive Story of the American Drive-In Movie. This one about movie palaces is a follow-up, because they’re very similar. They’re both about ways that we experience movies that are in decline because of cultural shifts and other things that have impacted communities and neighborhoods.

Especially movie palaces, but drive-ins too, have been cultural centers for the neighborhood. A lot of communities tore them down to turn them into things like parking lots. I didn’t know all that going in. I really just couldn’t understand why these places were being torn down, why they were destitute and in such bad need of repair. I really wanted to know why they weren’t around more.

Like drive-ins, which were the object of your previous film, movie palaces represent a certain nostalgia. Why is it important to talk about these kinds of attractions that are in decline today?

These are places where people could share a communal experience: They were community gathering places, family gathering places. Through the decades, there have been financially-driven decisions where communities haven’t paid enough attention to save these things. But one of the things that I love is that it took a person from the community to stand up and save the ones that are left.

A lot of times, when movie palaces are not saved, they become a Walmart or another place where you just buy more. Over time, looking at the impact of these decisions on communities and people and families, I don’t think it’s necessarily good impact. I’m not sure that it’s progress.

When these places are saved by communities, they keep history within that community and promote that gathering place. [The theaters in] Going Attractions are all these communal attractions that we went to for so many decades. I would include roller rinks in them, bowling alleys, family-owned amusement parks… Now everything is becoming so corporatized, so it’s hard for these places to survive. I think it’s sad. They’re cultural landmarks, to many people outside the United States and also here, and they need to be preserved.

You’re saying in the documentary that “other countries built palaces for royalty. In the United States, we built them to watch movies”. What does that show about the place of movies in American culture?

It explains just how important movies were to us. Especially at the time movie palaces were built, which was during a compressed time period between the 1910s and the 1920s, around World War One and going into the Great Depression. [There wasn’t] much money going around, and yet millions and millions of dollars were put into building these ornate movie palaces. Creating these palaces to have such a unique experience shows the significance that the movie industry had in this country.

I think there’s also a shift. For generations, it has been a special experience to go to the movies and see movies in places like this. A lot of the filmmakers who are revered, whether it’s Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, or Steven Spielberg, talk about going to the movie theaters and having that magical experience. I think newer generations might feel different about movies because they’re watching them on a computer without having that communal experience. I’m afraid that over time, the idea of moviegoing as something magical might be eroding a little.

It’s very interesting in the sense that American movie palaces had the exact opposite social effect from other palaces: they were a place to equalize the social status of patrons, not divide them because of their wealth.

Isn’t that very American? The idea that anybody can go to a movie palace and be treated like royalty by these ushers equally.

Do you think that the unique experience provided by movie palaces is something that can help revitalize them?

I hope so. A lot of them that are open now are serving different purposes. Many are performing arts centers where you can see travelling Broadway shows and concerts. I think a lot of people go to these places without realizing that they were movie theaters. Because why would they? They are big and beautiful. These places that provide a lot of different things are doing really well. But there are also a lot of historic movie palaces that are still only showing movies. Some are showing classic movies. but some also show first-run movies.

As a moviegoer, when I was growing up and going to college, if I had a choice to go to a multiplex or go to an old movie palace—even if it was in bad condition—I would go [to the movie palace], because I felt like it was a better experience. There are still people who know that these exist and support them by attending regularly. They’re a great place to watch classic films the way they were intended. It’s a different experience. You feel the film in a different way. It becomes more memorable. But I also see that a lot of movie palaces are struggling. Part of it is just the cost of maintenance, especially if they have the landmark status and there are some requirements they have to meet. So they’re constantly in raising-money-mode.

As a lot of the people you interviewed said the movie palaces’ success depended a lot on the “persona of the showman,” like S.L “Roxy” Rothafel or Sid Grauman. What do you think exhibitors today can learn from these showmen?

I don’t think there are people today that represent the showman. [Now there are] brands like Alamo Drafthouse, where you can get food and drinks and have a more retro program; or ArcLight, where there’s an effort to provide a more prestigious experience. Some smaller theater chains are creating a sort of branded experience in the same way that these showmen used to.

Most of the efforts for the preservation of movie palaces came from people within the neighborhoods where they operated. What can people do to save movie palaces?

People need to get involved with preservation groups. On a high level, there’s the Theater Historic Society of America. They helped my film by opening up their archives to me. They’re a great resource to get involved if you care about old theaters. Locally, in Los Angeles for example, we have the Los Angeles Historic Theater Foundation and the L.A. Conservancy that are protecting all historic sites. There are groups that you can find in your local area and get involved with. The public can also just support these places when they do re-releases of classic films. It’s a way to support the buildings and participate in film education, as you can see classic films just the way they were intended to be seen by their filmmakers.

Can you tell us about your research process?

Now that I’ve made a couple of historic documentaries—I’ve actually made a third one about stunt women that isn’t out yet—I’ve done three movies on different aspects of Hollywood history. First, I try to research as much as I can so that I understand what happens.

What another documentary filmmaker told me is that you need to make a documentary from the inside. You can’t really come from the outside and impose your thoughts on them. You have to get involved with the group. Once you do that, they will start to tell you what the film is about. They will start to tell you who should be in your film and who to go talk to. They will tell you how to tell the story.

In the case of this one, I did some research and Leonard Martin was one of the first people that I got. I knew he was a renowned critic and that he knew film history. But I saw him speaking once—I can’t remember if it was at the Ace Hotel or at the Cinerama Dome—and I realized he was extremely knowledgeable about theater history, too. I talked to him and got him involved. Then you find a basic outline of your topics and of who is going to be talking. You kind of map it out to make sure you got coverage and that each person has an area where they shine and are the experts. I also try to show diverse perspectives and make sure that I have all kinds of different people, that I have women, people of color… I’m just trying to make sure that I show all sides and all perspectives.

Is there a moviegoing moment that was key in your love for movie palaces?

Actually, my answer is “no,” because movies were such a big part of my life. We went to the movies all the time. I definitely remember seeing Rocky at a theater when I was pretty young. My mom had already seen it, but she wanted me and my siblings to see it, too, because it was a story of underdogs and resistance. That’s still one of my favorite movies to this day. I also remember my brother and sister working at our neighborhood movie palace down the street and going there when Raiders of the Lost Ark came out and seeing that movie at least forty times in that theater. Especially in high school and college, I went to every single movie that ever came out.

Will you be screening the documentary in movie palaces?

Right now we are doing a lot of preview screenings in festivals. I’ve been to five festivals, and we’ve won top awards at four of them. We’re having our big theatrical world premiere in Los Angeles at the Laemmle theaters on October 24th, followed by a week-long run at five Laemmle locations. Then we’ll have our Chicago premiere on November 1st at the Music Box, one of the movie palaces featured in the film. It has its ninetieth anniversary this year. And then we’re booking everywhere, playing all around the country!

After I made the drive-in documentary, I had a really good response theatrically, so I knew people would like this one. There’s also a lot of talk right now about where the theatrical experience is going, so I think more people are interested in preservation and paying attention to older things that matter. I believe the film explains a lot of questions that people might have right now about why some things are happening. The timing has helped in making people responding more passionately about it. This is such an important and critical part of the history of cinema and exhibition, and I think when you see the film it helps you understand why it’s important to save the ones that are still left and preserve some of that living history.

Share this post