The world’s not hurting for Jane Austen adaptations. Your nowhere-near comprehensive list includes: Last year’s Sanditon miniseries, from Austen vet Andrew Davies (Pride and Prejudice, 1995; Sense and Sensibility, 2008). Three years earlier came Whit Stillman’s Love & Friendship (“How jolly! Tiny green balls.”), based on Austen’s early novella Lady Susan; Stillman’s 1990 film Metropolitan is a loose adaptation of Austen’s Mansfield Park, which was tackled in a more straightforward fashion by Patricia Rozema in 1999. Pride and Prejudice had zombies that one time. And, in what is still the best Jane Austen adaptation ever made, Alicia Silverstone reminded us that it does not say ‘RSVP’ on the Statue of Liberty.

Joining this august company (uh, except the zombies one) is Autumn de Wilde’s Emma, with which its youthful flair and fun vibe puts it in the top echelon of Austen adaptations. Out in limited release now from Focus Features, the film will expand to wide release on March 3.

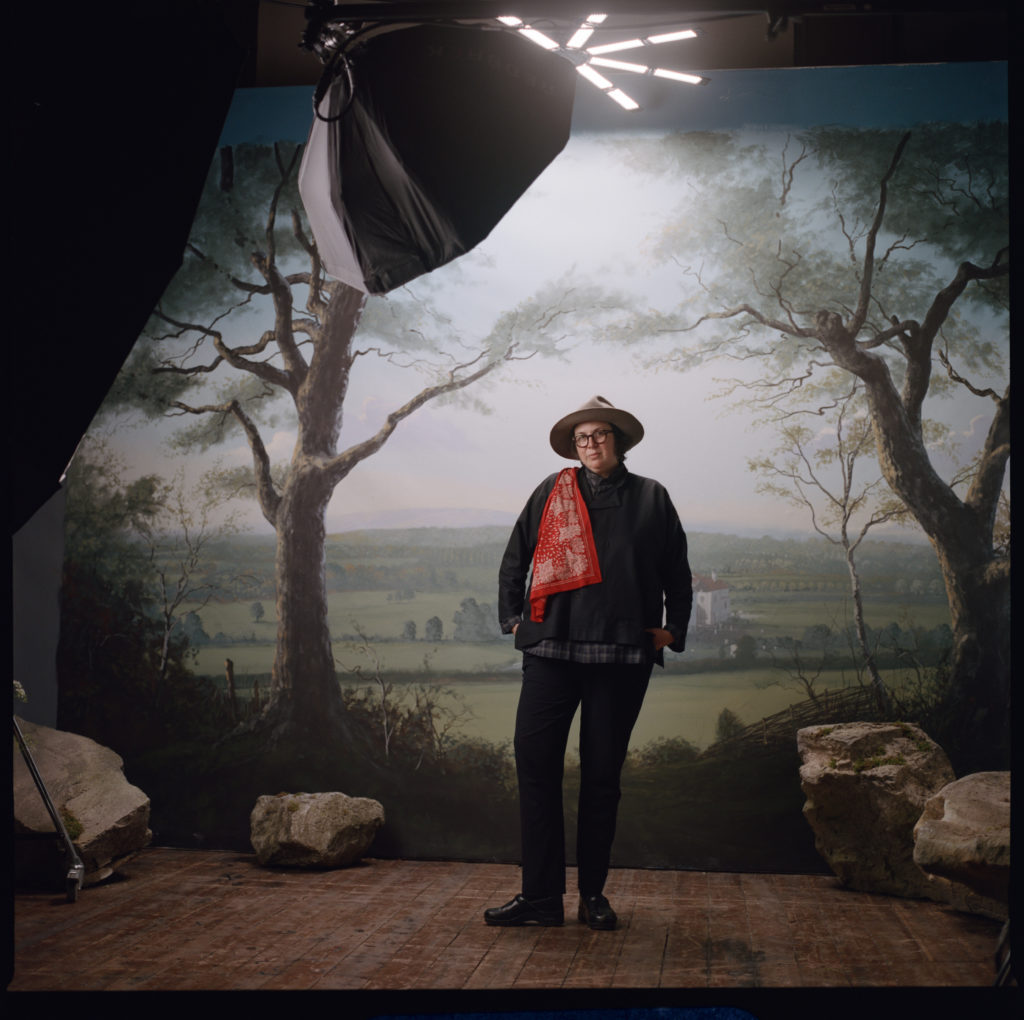

Emma marks a feature debut for de Wilde, a photographer and director who’s worked extensively in the world of music videos, commercials, and portraiture. The bold, bright visual style she honed through that earlier work finds a perfect outlet in Emma, the story of a young woman—“handsome, clever, and rich,” Austen tells us right off the bat—who, out of pride and a lack of anything better to do, inserts herself into the romantic lives of her neighbors. Emma is “a mean girl who doesn’t realize she’s men, which is a really specific type of person” opines de Wilde. “They think that everything they’re doing is for the betterment of others. But it’s really for themselves.”

Emma runs her father’s (Bill Nighy) household and is rich enough that she feels no pressure to get married. She’s the town’s queen bee and its tastemaker; in a wonderful bit of storytelling-by-clothing from costume designer Alexandra Byrne (Elizabeth, The Avengers, 300), Emma’s poor, orphaned protege, Harriet (Mia Goth), begins to dress more and more like her mentor over the course of the film. de Wilde recalls one of Byrne’s costumes for Emma in particular: a dress with a high, ruffled collar that nonetheless leaves ample cleavage exposed. “[Screenwriter Eleanor Catton] was like, ‘Oh my God, it’s like the night before she told Harriet, “Let’s wear high collars.’ So Harriet is covered to here. And Emma’s covered to here, but showing here.”

Also an Emma highlight: A very, very on-point fancy bonnet game.

“There was a hair story and a costume story” for every character, de Wilde recalls. “Emma starts out very like a little girl, with her doll’s hair. Her curls start moving back, and she becomes more of a hot mess as wheels come off the wagon.”

And off the wheels do come. Because Emma, rich and powerful within her own little universe as she may be, is still a young woman with a flair for the dramatic. It’s de Wilde’s appreciation of that fact that puts her Emma more in line with Clueless—which imagines Emma as a pampered valley girl ruling over her Beverly Hills high school—than Staid, Sophisticated BBC Jane Austen Adaptation #345.

“That’s why Clueless is such an incredible movie. Because [writer/director Amy Heckerling] understood that [the characters are] basically in high school,” de Wilde argues. “Emma is 21 and has never gone to school with other girls. And Harriet is the first girl that isn’t her paid companion…. [Emma] is a romantic fantasy, but it’s also that fantasy of that asshole friend of yours amending their ways. Because everyone has that friend who treated you terribly, and there’s a fantasy that they’ll realize they’re wrong.”

de Wilde’s Emma, played by The Witch star Anya Taylor-Joy, has a fun edge that other incarnations of the character often lack. Though ultimately a sympathetic character, she lacks the angelic sweetness of, say, a young Kate Beckinsale (Emma, 1996). You get the sense that this Emma genuinely believes she’s fundamentally better than other people. de Wilde believes that in a “successful high school movie, [you] have some sympathy for a tormentor. You sort of love the main cheerleader, even though you’re rooting for the underdog that’s at the heart of it.” (Cady Heron may be the main character in Mean Girls, but you’d be pressed to find someone who doesn’t love Regina George more.)

Emma, of course, eventually does get her comeuppance; she realizes that maybe she does have some character defects of her own to work on, one of which is her insistence on meddling in other people’s love lives. On that point—the unraveling of the web of romance lingering just beyond Emma’s awareness—de Wilde calls Austen’s novel “one of the most important novels ever written. It’s the first detective novel. Agatha Christie based her style on Emma. All the clues are in the book, but you don’t realize you’ve read them until… some secrets are revealed. And when you go back and read it a second time, you realize that you were told everything that was a secret. You just didn’t notice it. Christie based her detective novel style on that work. The second time around, the clues were there.”

Helping Emma along on her path towards maturity—though de Wilde is careful to note that she nudges him right back—is Mr. Knightley, played by musician/actor Johnny Flynn. The pair has an electric chemistry that comes to a head not in the proposal scene (uh—spoiler that there’s a proposal scene in a Jane Austen movie) but in a post-ball scene that sees Mr. Knightley running through the streets of Highbury to Emma’s house after realizing he has romantic feelings for her. “We called that my Jason Bourne moment. I told my editor this. I told Johnny when we were filming him: ‘This is the only action part of this movie.’”

It’s a scene with practically no dialogue, which “you might not realize,” says de Wilde, is true of several sequences in Emma. If that seems like an odd choice for an adaptation of one of Western literature’s greatest dialogue-writers, de Wilde makes it work.

Her early work in photography and music videos lends itself to visual storytelling; later on, when she wanted to get into commercials, she found that “I could never get a script with words in it. They didn’t think I could handle it. So I started writing very complicated stories with no words. All the actors had all this stuff that was being unsaid going on. And I got really good at telling a lot of story without words.” At that time, de Wilde notes, the worlds of photography and commercials were largely “male-dominated.They don’t want to give you the job unless you’ve shown that you can do it [already]. …Honestly, I benefited from that, because I had to work around these things to convince people. I started getting jobs based on things [where] I think they hadn’t realized there was no dialogue. Instead of letting it hinder me, I used it to advance in a strange way.”

Emma’s characters do trade witticisms, but they also dance, fidget, power dress (“No color is too bright as long as it looks delicious” was the rule on-set), and exchange a scorching look or two: “It’s so exciting to play with the restrictions of the time period. You can imagine the intensity of desire when you can’t show it all. That sort of restriction, to me, is very sexy.”

They also cry quite a lot. “I remember one person [who saw] the early cut was like, ‘Is there too much crying?’ And I’m like, ‘No. This is what it’s like to be a young woman.’ There’s a lot of different types of crying. There’s shame. There’s true regret. There’s petulant hurt, when you’re like a child who’s done something wrong, and you’re mad that you’ve gotten caught, and that makes you cry. Anya’s such a brilliant actor. We planned out the types of crying”—all the way up to (gasp) a reversal, where it’s not Emma but Mr. Knightley who’s letting some distinguished tears fall into his cravat. “I love that she thinks it’s funny that’s he’s crying. It was really important to me and Anya and Eleanor, who wrote the screenplay,… that Emma’s not tamed. It’s not The Taming of the Shrew.”

Share this post