2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of Boxoffice Pro. Though the publication you hold in your hands has had different owners, headquarters, and even names—it was founded in Kansas City by 18-year-old Ben Shlyen as The Reel Journal, then called Boxoffice in 1933, and more recently Boxoffice Pro—it has always remained committed to theatrical exhibition.

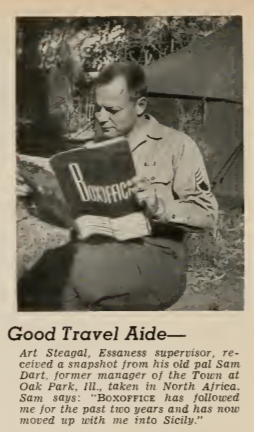

From the 1920s to the 2020s, Boxoffice Pro has always had one goal: to provide knowledge and insight to those who bring movies to the public. Radio, TV, home video, and streaming have all been perceived as threats to the theatrical exhibition industry over the years, but movie theaters are still here—and so are we.

We at Boxoffice Pro are devotees of the exhibition industry, so we couldn’t resist the excuse of a centennial to explore our archives. What we found was not just the story of a magazine, but the story of an industry—the debates, the innovations, the concerns, and above all the beloved movies. We’ll share our findings in our year-long series, A Century in Exhibition.

The 1940s started with the exhibition industry rocked by changes stemming from an external source: World War II, which impacted where films could be distributed and how theaters could be run. The Allied victory meant the U.S. government had time to return its attention to something that remains, decades later, a hot-button issue in our industry: The Paramount Consent Decrees.

The motion picture industry entered the fourth decade of the twentieth century with a combative attitude; the outbreak of war in Europe did not leave Boxoffice Pro, much less the industry as a whole, indifferent. As early as fall 1938, Boxoffice Pro spearheaded the industry’s effort to promote “Americanism,” a collection of American values that include patriotism and fighting back against dictatorships.

Cecil B. DeMille’s documentary Land of Liberty and John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln emphasized patriotic themes, while films like The Great Dictator, Confessions of a Nazi Spy, and Inside Nazi Germany took direct aim at Hitler and the Third Reich. Owner/editor Ben Shlyen identified these films as an important part of the war effort. There were more coming; a July 1939 feature identified at least 42 “Americanism” films slated for release through the end of the year. In that same piece, editor-in-chief Maurice “Red” Kann wrote, “no one can successfully argue that the screen should not do everything in its considerable power to maintain and perpetuate the good things in the American scene.”

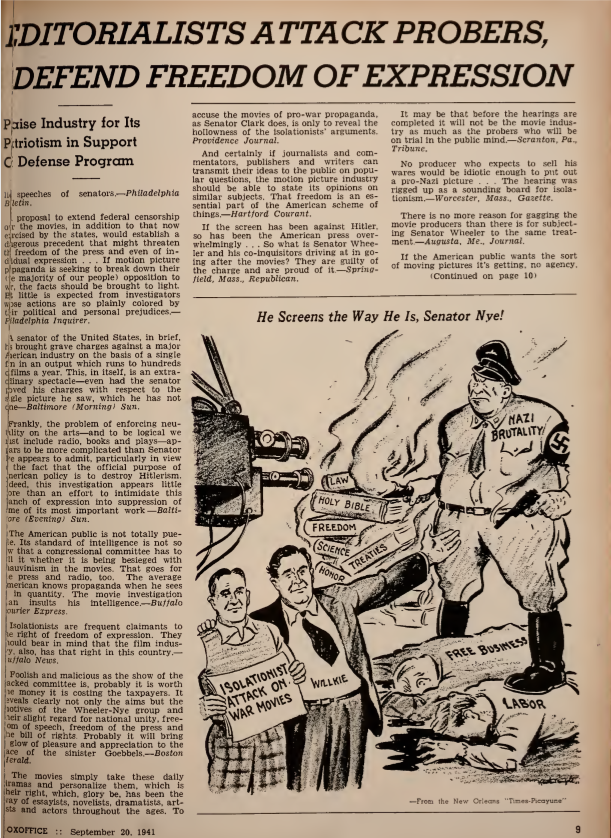

Americanism did not fall on sympathetic ears in Washington. In 1941, a Senate sub-committee launched an investigation into the motion picture industry, accusing it of warmongering and of violating neutrality law. Needless to say, Boxoffice Pro fought against what it perceived as censorship.

Red Kann accused the committee members of using the industry “as a springboard for an isolationist support on the administration’s foreign policy.” (In fact, four out of five sub-committee members were isolationists.)

Both Shlyen and Kann feared that studios being labeled peddlers of propaganda could have catastrophic consequences at the box office. In September 1941, Kann warned that “one grave danger, perhaps the gravest, confronting the industry is the possibility [that the probe] may succeed in establishing a link in the public mind between the industry and propaganda, thereby making suspect whatever Hollywood may produce and newsreels may report with feared effects on the box office.” Kann also applauded efforts by the Hays Office to stop the probe, writing “after years of taking it square on the chin and folding up under the impact of criticism […] the industry now discovers its backbone and returns the blows.”

The motion picture industry did not stand alone in this battle. A survey conducted by the Hays Office and published inour pages in October 1941 found that 90 percent of editorials in American publications were in support of the motion picture industry rather than the Senate sub-committee. Editorial support from various outlets praised the industry’s patriotism and attacked the Senators’ attempt to curtail freedom of expression.

Everything changed with the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. As the U.S. officially entered the war, the probe was dropped. A few days later, Shlyen urged the industry to unite, less for its own benefit than for the nation’s welfare. Soon after, the Motion Picture Committee Cooperating for National Defense, established in 1940, changed its name to the War Activities Committee and began the work of supporting the war effort.

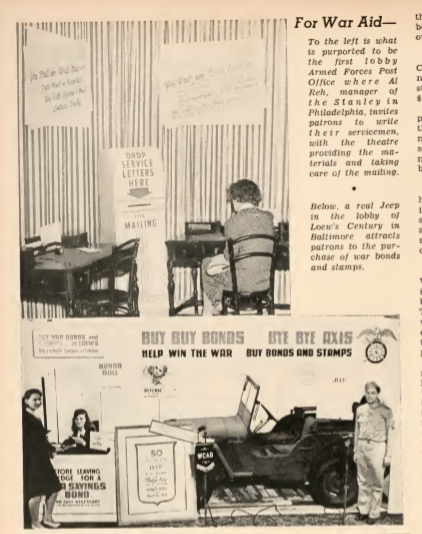

Boxoffice Pro ran campaigns to inform exhibitors about how they could contribute as well. The magazine proved a staunch supporter of many industry-wide drives to collect money to support refugees and encourage the purchase of war bonds. Throughout the war, the magazine often ran pleas for theater owners to conserve precious materials, like copper drippings and aluminum, and offered instructions on how to recover them from projectors and other equipment. The pages of Boxoffice Pro also documented—and often applauded—various exhibitor efforts to encourage patriotism among their patrons, whether through the use of lobby displays promoting the purchase of war bonds, running “‘D’ for Democracy” banners on marquees, or hosting training for “airstrike wardens.”

The magazine also kept readers up-to-date on the grim reality that faced theaters as the war progressed. With rationing, popcorn became increasingly scarce. Film shortages caused frequent delays in film delivery. Fuel shortages forced theaters to modify their hours or shut down temporarily. In 1942, the War Production Board issued orders forbidding the construction of new theaters for the remainder of the war. There was a high cost in terms of manpower, as well, as many in the industry—from exhibition executives to lower-level staff—joined the military, putting them alongside Hollywood stars like Charlton Heston, Jimmy Stewart, and Clark Gable.

The exhibition community also faced a crumbling demand, both domestically and abroad. Just two weeks after the start of the conflict overseas, Boxoffice Pro writers joined studio executives and prominent exhibitors in calling for a self-sufficiency strategy that would rely solely on U.S. distribution. In 1940, 20th Century Fox’s Darryl F. Zanuck stated, “We’ve got a grave responsibility – to place ourselves in a position where we are domestically self-sufficient. When we have done that – and we must do that – then and only then we’ll last forever with the destiny of our business in our hands.”

By the first six months of 1940, film exports to Europe were down by six million feet compared to the same period in 1939. A commentator jokingly wrote that Hitler controlled the largest theater chain in the world. With Europe in turmoil, the industry turned to Latin American markets for their exports. In May 1940, Red Kann estimated that the loss of foreign markets would amount to an annual $50 million deficit during the war.

As the end of the war approached, the film industry looked to the financial potential of the liberated markets. In 1943, Boxoffice Pro reported that French director Julien Duvivier believed that the French, “being an emotional people, [required] substantial food for their minds,” which “must be supplied” in the form of American films. That same year, we reported that crowds in Italian theaters were chanting, “We want American films again.”

After 1945, there was a sharp increase in exports, owing to both the post-war economic boom and the presence abroad of American troops, which were stationed in such numbers as to offset the impact of trade tariffs. By 1947, the vice president of the Motion Picture Export Association stated that “American pictures have recaptured their prewar prestige and are again the preferred entertainment in every country I visited.” Foreign films were also becoming popular in the U.S.; also in 1947, 250 theaters showed pictures from overseas

Boxoffice Pro expressed hope for the industry moving forward, publishing articles on the post-war “theater of the future” and praising the return of innovation. However, the return of business as usual also meant the return of a legal battle that had preoccupied the industry for decades: the anti-trust question.

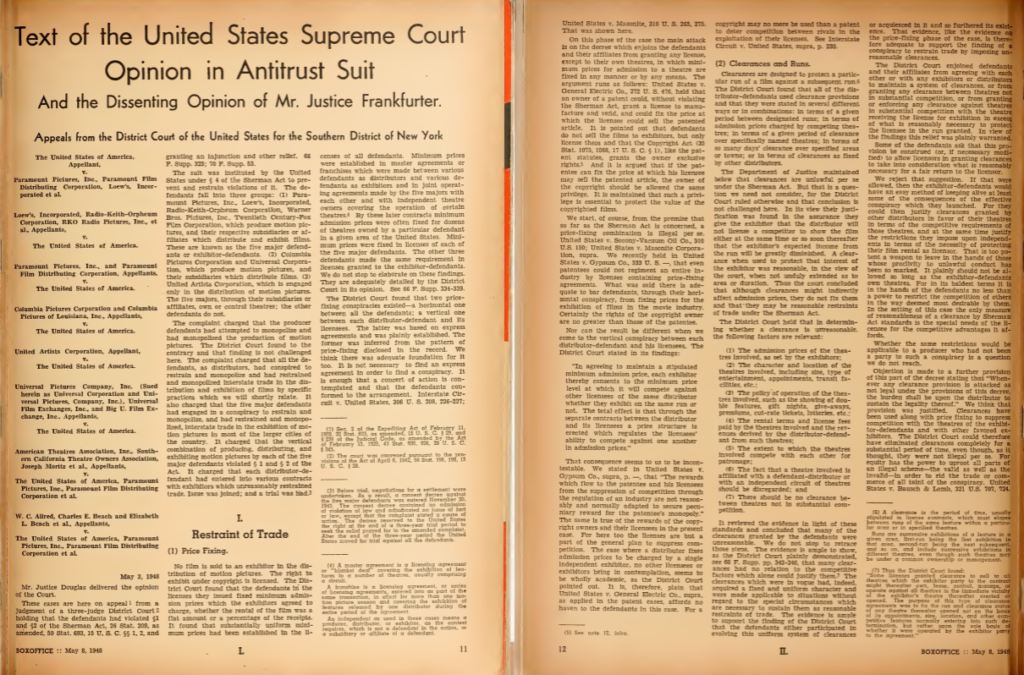

It all started in 1921, when the Federal Trade Commission declared block booking anticompetitive and questioned the studios’ monopolistic practices. Nine years later, the major studios were declared guilty of monopolization, but the decision was nullified by the Roosevelt administration during the Depression. In 1938, as studios became more powerful, the Department of Justice filed another antitrust suit against the Big Eight (Paramount Pictures, Twentieth Century-Fox Corporation, Loew’s, RKO, Warner Brothers Pictures, Columbia Pictures Corporation, Universal Corporation, and United Artists Corporation), accusing them of conspiring to control the industry through the ownership of both distribution and exhibition channels.

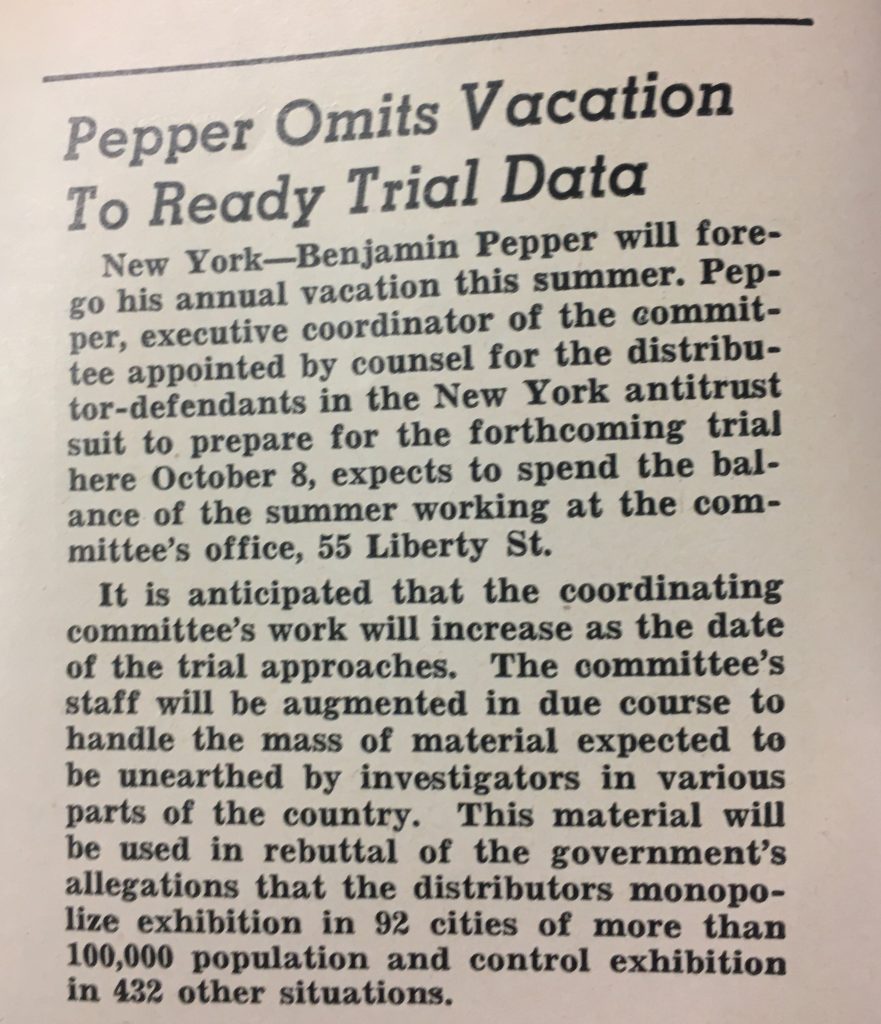

A 1940 article reported that between 1930 and 1940, exhibitors had filed 793 complaints with the Justice Department. That same year, studios reached a deal with the Justice Department: During a three-year trial period, studios could keep ownership of their theaters, but block booking was limited to groups of five and exhibitors were allowed to watch movies before purchasing them. An arbitration system was enacted a year later. This consent decree ended in 1943 when the Department of Justice filed yet another lawsuit, which was put on pause due to the war.

The end of the war led the Justice Department, with the support of the Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers (SIMPP), to renew the case. In 1948, after two decades of legal battles, the Supreme Court handed down its order abolishing block booking, circuit dealing, and resale price maintenance. Studios would also be forced to divest themselves of their theater chains or spin them off into discrete new corporate entities. RKO was the first studio to sign the consent decree in November 1948, followed by Paramount in May of the following year and Loew’s, Fox, and Warner in July 1949. The series of consent decrees that were formalized during that period came to be collectively known as the Paramount Consent Decrees.

The exhibition industry was far from united on how it viewed the consent decrees. The Motion Picture Theater Owners of America (MPTOA), predecessor of NATO, was in favor of self-regulation over federal regulation. Its president, E.L. Kuykendall, declared in April 1940 that “we know [the independent theater owner] has reached the stage of favoring any regulation, or law, whether he would benefit by it or not since he has little to lose anyway. But, in any instance, he has allowed a temporary cloud to blind his vision and he will eventually learn he will suffer most if such legislation is enacted.” In reaction to the decrees, Shlyen wrote: “The industry has its greatest opportunity to date to come through with a trade practice plan designed for elimination of inter-factional troubles.”

But, like Kuykendall, Shlyen thought the decrees wouldn’t solve the industry’s problems. Exhibitors and distributors, he believed, “must sit down and agree on terms that will best serve their mutual interests.” In 1946, Shlyen wrote that “the government’s failure to win its ‘main issue’ of divorcement”—which it would go on to “win” two years later—“[was] actually a victory for the independent exhibitor.” Going back to the self-regulation argument, he wrote in 1949 that the long legal battle “has drained the industry of millions of dollars and the time and thought which otherwise would have been devoted to production improvement and merchandising.” Ultimately, for Shlyen, it was hard to assess the real impact of the Decrees. That wouldn’t reveal itself until future years.

Share this post