By Daniel Eagan

The below interview was conducted for Film Journal International in the summer of 2017, tied to the release of renowned director Bertrand Tavernier’s Journey Through French Cinema. Boxoffice Pro republishes this piece now following Tavernier’s death on March 25, 2021.

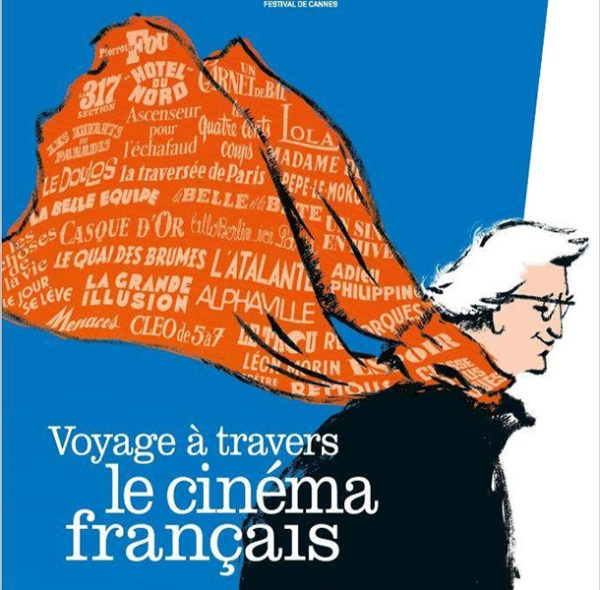

In his latest work, My Journey Through French Cinema, Bertrand Tavernier gives an account of the movies and artists who influenced him. Like the director himself, the documentary is warm and engaging, filled with first-hand details that offer new insights into the hallmarks of French filmmaking. The Cohen Media Group release opens today in New York City.

In his narration, Tavernier gives a short version of his childhood in Lyon and his love affair with movies. He then analyzes some of his favorite cinema artists—actors, composers and screenwriters as well as directors—in segments lasting from ten to twenty minutes.

Tavernier doesn’t talk much about himself in his voiceover, so it’s worth noting how passionately he involved himself in the film industry, first as a founder of the Nickel Odeon club, then as a critic, actor, assistant to Volker Schlöndorff and Jean-Pierre Melville, and press agent for Rome-Paris Films. He had broad experience in the industry before directing his first feature, The Clockmaker, based on a novel by Georges Simenon, in 1974.

“What touched me about the novel were the emotional issues, how the father is getting closer to his son when his son is on the run,” Tavernier says. “The father’s trying to understand what happened, learns that he never really talked with his son, never knew him, but he’s going maybe to know him a little bit better. In most other films, people go from A to Z. Here you are going from A to C or D. Small steps.”

My Journey Through French Cinema opens with a segment on Jacques Becker, whose titles include Casque d’Or and Touchez pas au Grisbi. (Coincidentally, a restored version of his last film, Le Trou, opens on June 28 in New York.)

“People in his films are always doing things, carrying water, cutting trees, they are always busy,” Tavernier points out. “Maybe I was influenced by Becker because I loved his way of telling the story, but also by the way everybody in his film was working. So in The Clockmaker and L.627, even in ’Round Midnight, I am trying to show jobs, work, and emotions connected to work.”

Tavernier suggests that he may have absorbed the work of directors like Becker and Jean Renoir without fully understanding how they influenced him. “I remember being very impressed, very early, by the way Jean Renoir was moving the camera,” he recalls. “It was never just functional, it wasn’t just to follow or proceed somebody walking. The camera was revealing something more about space, about the position of characters in the space, in the landscape. It was a way also of connecting several layers of action with people, often through overlapping dialogue.”

The director agrees that during the height of the studio system, it was easier for directors to control and manipulate the frame and action within it, skills modern-day directors often seem to lack.

“Digital cameras and effects may seem to make things easier today,” he concedes, “but as my friend André de Toth once told me in Lyon, ‘They are only tools. They cannot replace vision.’ And on the other hand, digital can give a freedom to some shots, help you avoid the dictatorship of composition. In Robert Altman’s films, for instance, nothing seems composed.”

Tavernier adds that tools like Steadicams and handheld camera rigs can make shots look “accidental,” not designed. “To get that look took a lot of time in the old days,” he jokes. “John Ford told me once the reason why he always tried to get the scene on the first take was because you always had accidents on the first take. He loved to incorporate those accidents into his movies, use them to break out of his scripts.”

Ford had a notoriously difficult personality, and in My Journey Through French Cinema Tavernier doesn’t ignore the flaws besetting Becker, Renoir, Melville and others. Renoir expressed troubling sentiments in letters that were published after his death. In Melville’s films he sometimes shows little sympathy for his characters, especially women.

“There can be a kind of coldness, a lack of empathy for any kind of human feeling,” Tavernier admits. “So I see clearly why some of Melville’s films move me less than Becker or Claude Sautet. But at the same time he was not trying to move me, he was trying for another kind of emotion. And in Army of Shadows he succeeded in getting everything right, because it was a subject that was very close to him. He had been in the Resistance, and in fact he incorporated some part of his life in that film.”

In his segment on Marcel Carné (Le jour se lève, Children of Paradise), Tavernier includes highly critical comments from screenwriters Jacques Prévert and Henri Jeanson.

“They didn’t like him, but they were not fair,” he argues. “I agree with some of what they said—I don’t think he had a great instinct for actors, and he could not write dialogue, that’s true. But he was such a tough worker, and he had such a passion; in his way he was breaking the shot, getting the relationship between this shot and the next, he was transcending the story. As screenwriters, Prévert and Jeanson couldn’t perceive that, they underestimated him. He wasn’t just ‘photographing’ the screenplay, he was giving it power, strength.”

Tavernier says movies like 1937’s Le jour se lève with Jean Gabin, a precursor to film noir, made him a fervent admirer of Carné. “Look at the beginning of that film, how he takes the most uninteresting setting, a very poor city hotel, nothing visually exciting, and how he makes every shot great, has every shot moving the story forward. Contrasting high and low angles, thinking about the lenses, how you manage to film in a very tight set—that opening sequence should be a test for every director.”

The director says that the way Carné (and Melville, Henri-Georges Clouzot and other directors) filmed reverse-angle shots had a big impact on his own filmmaking. Especially in television, directors often film conversations in a shot/reverse-angle shot formula because it is easy and cheap.

“Carné mastered them, particularly in Le jour se lève,” Tavernier says. “Melville too, his shots are so symmetrical that he makes an art out of the cliché. I always try in my films to be asymmetrical. When I had a shot on somebody, the reverse is over the other shoulder, for example, with a completely different lens. But Carné showed me that the reverse can be so beautiful that one must not be afraid of it. He made an art out of symmetry.”

Tavernier points to Renoir’s use of a moving camera, how it opened up the world outside the frame, as another example of influence on his directing style. “You must never forget what is behind the characters,” he says. “When you are for instance shooting a scene in a restaurant, people eating a meal, I always try to incorporate some kind of background action so it will not be a static shot. Somebody passing behind, trying to include a window, trying to get something that will make the shot interesting, and not rely only on the shot and reverse shot. I’m always trying to put a little disorder in that. I like disorder. For me sometimes, a shot and reverse shot seems too clean, too easy. So I like to destroy that order a little bit.”

In My Journey Through French Cinema, Tavernier gives examples of how editing adds emotional weight to a conversation. “For me, direction is music,” he explains. “I think I have a good sense of music. My cuts are musical. There is a moment in the rhythm of a scene in which you might need a wide shot, not for any narrative reason, but to let viewers breathe.”

At one point he jokes about how Melville used rulers to line up shots. When Tavernier tells stories about Melville, Sautet and Ford, he is drawing from his personal experiences with them. Early in his career he sought out filmmakers like Howard Hawks, Raoul Walsh, Stanley Donen and Michael Powell, interviewing them in order to learn from their work.

“I believe the fact that I was interested in meeting all these people, it shows in my films. I was always interested in subjects that nobody did before. Nobody had used the setting for Let Joy Reign Supreme. Before ’Round Midnight there were very few films about jazz with jazz musicians. Life and Nothing But, there was nothing about that period. I tried to show how schoolteachers, cops, soldiers lived. How people worked during the Occupation, for example. The passion, the curiosity I had in meeting those people I hope is in synch with the passion and curiosity in My Journey Through French Cinema.”

If Tavernier’s documentary seems to concentrate on a dark vision of history, he points out that he was dealing with filmmakers whose forte was social drama. “I’ve just finished eight more hours, eight more episodes which will be shown on French television in October,” he adds. “There I talk about Pagnol, Guitry, Clair, Ophuls, Tourneur, even some forgotten directors who did musical comedies in the 1930s. So you will see a sunnier picture there.”

Share this post