2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of Boxoffice Pro. Though the publication you hold in your hands has had different owners, headquarters, and even names—it was founded in Kansas City by 18-year-old Ben Shlyen as The Reel Journal, then called Boxoffice in 1933, and more recently Boxoffice Pro—it has always remained committed to theatrical exhibition.

From the 1920s to the 2020s, Boxoffice Pro has always had one goal: to provide knowledge and insight to those who bring movies to the public. Radio, TV, home video, and streaming have all been perceived as threats to the theatrical exhibition industry over the years, but movie theaters are still here—and so are we.

We at Boxoffice Pro are devotees of the exhibition industry, so we couldn’t resist the excuse of a centennial to explore our archives. What we found was not just the story of a magazine, but the story of an industry—the debates, the innovations, the concerns, and above all the beloved movies. We’ll share our findings in our year-long series, A Century in Exhibition.

We began our series with last month’s overview of the 1920s, a decade in which the coming of sound heralded both excitement and concern among the exhibition community. In the ’30s, with sound well established, color became the technical innovation that drove the conversation. Then, as now, government involvement in the movie industry—specifically regarding censorship, taxation, and labor laws—also animated numerous conversations within our pages.

As the 1930s began, there was a strong sense of optimism throughout the motion picture industry. Buoyed by the success of the “talkies,” the industry was confident in its ability to weather an economic downturn in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash. As early as December 1929, Al Lichtman, United Artist’s head of sales, wrote that “all over the country, business at the box offices of theaters is fine. People turned to the economical form of entertainment that the movies represent for mental diversion.”

Studio leaders were equally optimistic. In an August 1932 Boxoffice Pro overview on the state of the industry, Adolph Zukor, president of Paramount-Publix, reassured that “there is nothing in this depression that good pictures, hard work and sound judgement cannot cure.” Universal Pictures’ Carl Laemmle even affirmed that “the depression has been a good thing for the motion picture industry, for it knocked out extravagant ideas and brought costs down to a sane level.”

The reality wasn’t quite as rosy. While after an initial slump in weekly attendance between 1929 and 1932, attendance levels were on the rise again, admission prices were dropping. Many chains were forced to cut prices. We reported that, for example, the Boston Publix houses slashed their prices by about 33 percent in 1932. That same year, RKO theaters cut overhead with economies of an estimated $2.8 million.

Nor were studios immune to budget cuts. In the late 1930s, Hollywood faced waves of studio layoffs and production halts. The second half of the decade saw Hollywood in paralysis as major strikes took place almost without interruption. Union workers from the major guilds picketed major studios and theaters in metropolitan centers, requesting a minimum wage, 42-hour weeks, and better working conditions. In the eyes ofwriters, the strikes were inefficient. In a 1937 editorial titled “A Lost Cause,” western bureau manager Ivan Spear explained that “theater patrons have only the option of seeing pictures made in Hollywood—mostly by the major companies affected by the strike—or of seeing no pictures at all.” In October 1939, Spear wrote that the “labor situation [was] again No. 1 problem of the film capital.” This conflict between studios and workers would persist well into the 1940s.

Meanwhile, the Great Depression gave new momentum to two debates about the motion picture industry that would define the decades to come: federal regulation and questions about the social responsibility of films.

The National Recovery Administration in Washington proposed a 10 percent tax on admissions in 1932, prompting a surge of local tax legislation. This was the beginning of a long battle against government interference in the film industry. According to owner/editor Ben Shlyen, in 1935 there were more than 140 bills in one (unnamed) state alone that targeted the movie business.

Boxoffice Pro was at the forefront of the fight against that taxation. Its contributors thought that government regulation and heavy taxation were the product of exaggerated reports of box office revenues. In an article dated February 23, 1935, Shlyen called the tax legislation a “discriminatory nuisance.” The magazine led letter-writing drives, inviting exhibitors to press their representatives to fight taxation bills. Just as taxation issues were making headlines, so were concerns about local minimum wage bills, child labor laws, and other economic measures that were seen as potentially harmful for exhibition.

At the same time, there was ongoing discussion among writers, exhibitors, studio executives, religious groups, and women’s clubs about the impact of films on society. One of the issues was the question of realism. The popular successes of The Grapes of Wrath, The Plow That Broke the Plains, and other “Dust Bowl Pictures” proved that movies were not resilient only because of their escapism value but also for depicting the reality of the Depression. But were these pictures going too far? Was it “propaganda with a message” as producer Jimmy Roosevelt—Franklin D. Roosevelt’s son—thought of The Grapes of Wrath?

No other regulation captured these debates better than the Motion Picture Code (1930–66), also called the Hays Code, which established a set of voluntary guidelines for producers. The Hays Code, named after its creator Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (now the MPAA), was enacted in March 1930 and effectively introduced censorship. With its series of “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls,” producers were called upon to obey “moral standards,” not ridicule the law, and avoid vulgarity, obscenity, profanity, and sex. Self-censorship and state censorship boards became the norm.

However, there were acts of resistance. Howard Hughes fought hard to stop the censorship of Scarface, accusing his censors of “ulterior and political motives” (May 5, 1932). While Hughes ultimately succeeded, it was harder for other movies. There was a lot of buzz in our pages concerning the educational film Birth of a Baby, which, in the end, censors deemed only suitable for specialized medical audiences.

In an April 8, 1930 editorial, written right after the adoption of the Code, Shlyen applauded the maturity of the industry, especially because he saw the proliferation of films with sex and violence as a threat. He wrote, “When an industry sets out to clean its own house it is a virtue that deserves to be

applauded. When it sets rules for itself to follow and follows them, it merits lauding to the skies.” In 1934, the Code had “its teeth sharpened,” per editor-in-chief Maurice Kann, when tighter regulations associated with conservative Production Code administrator Joe Breen were adopted.

In an April 8, 1930 editorial, written right after the adoption of the Code, Shlyen applauded the maturity of the industry, especially because he saw the proliferation of films with sex and violence as a threat. He wrote, “When an industry sets out to clean its own house it is a virtue that deserves to be applauded. When it sets rules for itself to follow and follows them, it merits lauding to the skies.” In 1934, the Code had “its teeth sharpened,” per editor-in-chief Maurice Kann, when tighter regulations associated with conservative Production Code administrator Joe Breen were adopted.

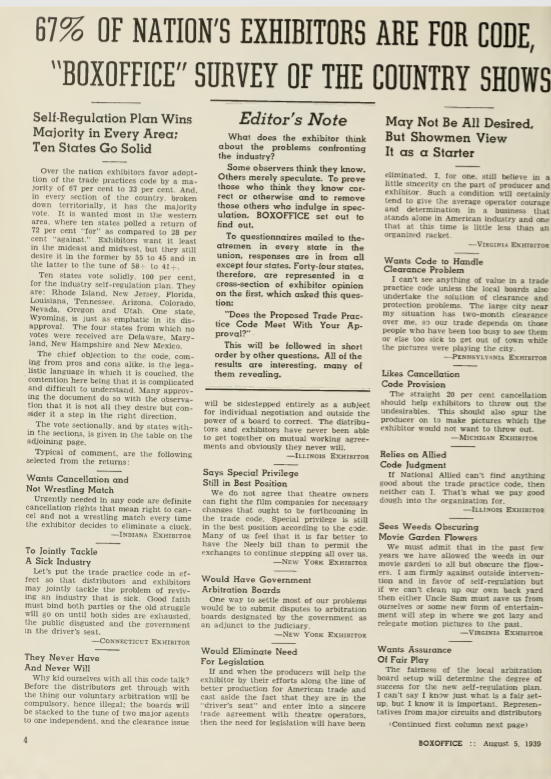

The Code was to become one of our most written-about topics throughout the decade. As time passed and the Code’s shortcomings became more apparent, Shlyen did not retract his support but instead advocated in favor of revisions. In a 1935 story, he wrote, “The Code has some good points few will deny. That it has enabled the industry to regulate itself and to restrain certain flagrant abuses also will meet with little denial.” He repeatedly called for more honest, fruitful debates and for better cooperation among producers, distributors, and exhibitors as a means of avoiding government censorship in favor of self-regulation. According to a 1939 Boxoffice Pro survey, that echoed the position of most exhibitors. Sixty-seven percent declared themselves to be in favor of the Hays Code but wanted better cooperation, less government intrusion, and more precise guidelines for cancellations and clearance. After endless back and forth between attorneys and exhibitor groups, the decade ended with a revised code—which was nonetheless not accepted by the Justice Department.

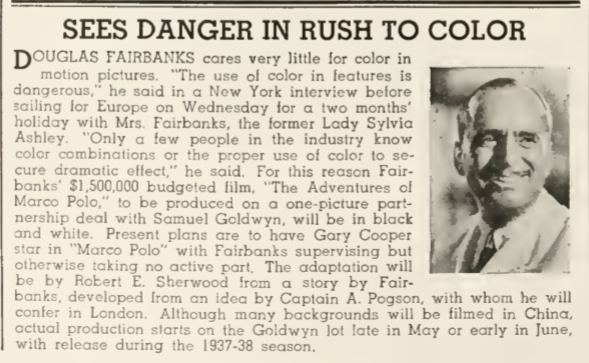

Despite the Depression and battles over regulation, the 1930s was also a decade of innovations, among them color. But much like sound a decade earlier, early uses of color were questioned by many in the industry. In March 1930, Shlyen wrote that he went into a color screening feeling fine but “came out with a headache.” He also criticized the lack of realism and the “unreal effect” of the technology. Shlyen believed that a more measured use of color would be more effective. Not all features should be color, he argued. In 1936, film star Douglas Fairbanks also warned that “the use of color in features is dangerous” because of the lack of expertise in finding proper color combinations.

The first 100 percent multicolor outdoor drama, Tex Takes a Holiday, proved to be a big box office draw in 1932. In 1935, Disney, beginning with the Mickey Mouse short The Band Concert, announced that all its future short subjects would be filmed in Technicolor. A year later, following the success of Paramount’s Technicolor picture The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, Lehman Bros., Atlas Corp., and Joan Hertz purchased Technicolor shares. In 1937, Samuel Goldwyn declared that he would produce his upcoming films with Technicolor, arguing that “color no longer interferes with the telling of the story.” Technicolor shares skyrocketed.

1936–1937 marked a turning point in the use of color, with the technology gaining more and more support. The use of Technicolor, which had improved its three-color method, had increased nearly 70 percent between 1935 and 1936. Acontributor even estimated a 300 percent increase in color features for the last two years of the decade.

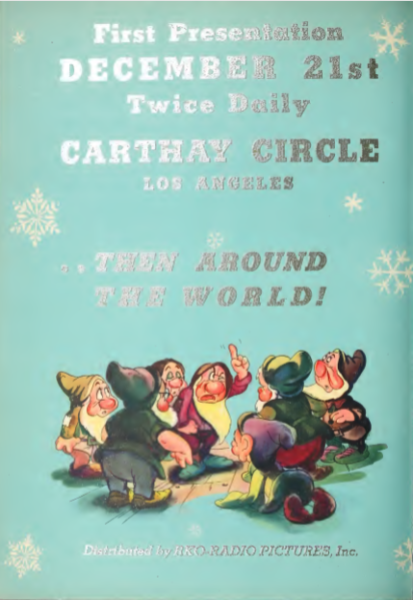

This innovation was a hit with moviegoers. A survey published in the magazine in April 1937 found that fans were asking for more color features. Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), the first animated feature to use color and sound, grossed an estimated $6.74 million by 1939, more than any other film to date. An exhibitor reporting on The Wizard of Oz (1939) stated that the novelty of color was more important than the film itself. Like sound in the 1920s, color came to revolutionize the nature of motion pictures forever.

Share this post