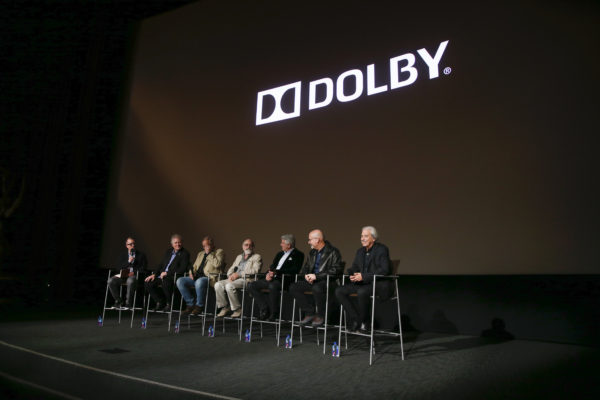

In a panel hosted by Dolby on February 7th, 2020 at the Saban Media Center Television Academy in Los Angeles, Donald Sylvester, supervising editor for Ford v Ferrari, Mike Minkler, re-recording mixer for Once Upon a Time in …Hollywood, Mark Ulano, production sound recordist and mixer for Tarantino’s film and Ad Astra, the Joker’s Dean Zupancic and Tom Ozanich, re-recording mixers, and supervising editor Alan Murray, discussed their feats in sound editing and mixing. Dolby Institute Senior Director Glenn Kiser moderated the discussion. The panel was followed by a celebration honoring the nominees for Achievement in Sound Mixing, Sound Editing, and Cinematography a few days before Hollywood’s big night.

“We’re here to celebrate some amazing artists,” said Doug Darrow, SVP cinema business group at Dolby. “At Dolby, one of the things we try to do as we think about this new technology is to talk to folks like this about how they want to tell stories and how they want to use tools and technologies that we are thinking about to bring it to life. What’s great is that when we see the things that they can do, they are far beyond what we could ever imagine. We have an idea, we have a solution, and we take it to a group of folks that bring it to life in ways that we never thought were possible.”

Dolby Atmos, which was used by all the best picture nominees as well as the sound mixing and editing nominees this year, was at the heart of the discussion. Currently, Dolby Atmos is adopted in more than 90 countries on over 5,000 screens.

Usually lauded for its effects in action sequences, the Joker’s trio defended Dolby Atmos’ strength for quieter scenes as well. “I think a lot of people misunderstand the use of Atmos and think it’s about using all these sound effects. It’s not just about that,” said Zupancic. Commenting on a scene from the Joker where Arthur Fleck does a stand-up bit at a comedy club, he explained, “It can be used in a scene which is much more basic but we’ve got elements in Atmos like the TV, where the sound turns as he walks by it. The detail that you can get with Atmos of movement, you can’t get that anywhere else with that level of precision and that adds to the feeling of reality.” “Because of Atmos, we were able to place the sound effects, and feel the intimacy of the club,” added Ozanich.

That precision was used to make audiences feel like they were in Arthur Fleck’s head, unable to distinguish what’s real and what’s not. “We refrained from using sound design to get you from reality to non-reality and back and forth. A lot of times if you’re going into an alternate space or mental capacity, you’ll use sound design, surreal sounds, some kind of tricks to get the transition. It was deliberate not to do that in order to keep the mystery of are we in reality or in Arthur’s head?” explains Zupancic.

Capturing the sound of revving race-car engines with precision was also crucial for Ford v Ferrari. The team had to go to great lengths to achieve that as most owners of the original race-cars were too scared to lend them to the production and the sound of the picture-cars’ engines were simply not convincing enough. They were finally able to locate a man in Ohio who built his own GT40 using original parts. Director James Mangold was so impressed by the sound of the engines that he initially wanted to shoot the entire Le Mans race with no music, explained Sylvester. “But there’s music in it, he came to his senses,” joked Sylvester.

Quentin Tarantino’s famous lack of traditional score composition (there were only 28 minutes of original score by Ennio Morricone in The Hateful Eight and a mere one-minute queue written for Kill Bill) left a lot of room for sound effects. “This is my 7th movie and [Tarantino] doesn’t ever want to loop a scene, or even a word, because he gets everything in the camera. Performances are there and he doesn’t use visual effects and trickery. Everything is done inside the camera so the production track is the production track, and that’s it. There’s no going around it,” said Minkler.

But, even if all effects are captured on set, for Minkler and Ulano, the long-time collaborations harbored by Tarantino allow the sound artists to “do some crazy-stuff”. The pair spoke about the famous Spahn ranch scene in Once Upon a Time in… Hollywood, where Brad Pitt’s character finds members of the Manson Family. “There was no music. It’s hundreds of little tiny pieces of sound that make this tapestry of weirdness and uncomfortableness,” pointed out Minkler.

The panelists also discussed the increasing convergence between sound effects and music in film. Speaking about the Spahn ranch scene, Minkler added, “Sound effects were music. Composers, what they do over a period of six months, maybe a year, of orchestrating the feeling of the scene and what they want to have the audience feel, that’s what we did with sound effects. It’s exactly the same thing.”

The observation was echoed by Zupancic who experienced that on a particular scene of the Joker when Arthur confronts two Wall-Street guys on the subway. The sound effects built up and when the crescendo hits its peak, the score slowly creeps in. “The sound effects, we don’t always have the opportunity to play as the score would play and Todd allowed us just to keep that crescendo point until the breaking point. That was a good dance.”

Finally, Ulano added “Atmos does allow a lot of precision, which is a very musical term to apply to this. I’ve been in conversation with Wiley [Stateman, sound editor] about him beginning to bring in more composers to consider orchestration with instruments inside the concept of placement through Atmos. We’re seeing this merging.”

Share this post