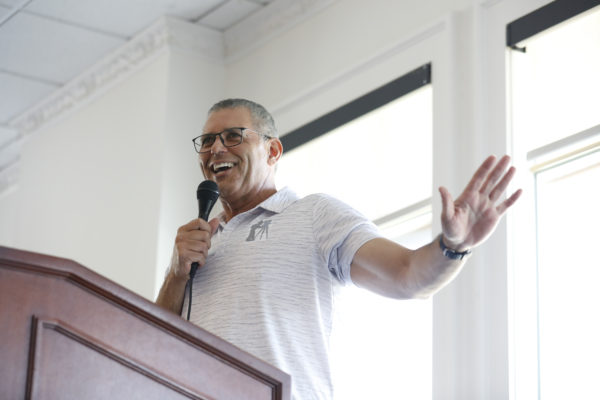

Ask Todd Vradenburg about the proudest moment of his career, and the question has to come with an asterisk: What was your proudest moment before 2020? Because, if you include the Covid era, the answer is obvious: As the executive director of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, Vradenburg oversaw the creation and implementation of Will Rogers’s Covid-19 Emergency Grant, which provided much-needed funds to over 10,000 cinema industry workers in 2020. In March of this year, after 25 years with Will Rogers, Vradenburg left the lead role at the charity to be the new president and CEO of NATO of California/Nevada, though he remains on the Will Rogers board. His time with Will Rogers, especially the thousands he helped during the Covid shutdown, will not be soon forgotten by a thankful industry. At this year’s Geneva Convention, there’s no better person to receive the Ben Marcus Humanitarian Award than Vradenburg.

Vradenburg had no intention of going into the cinema business, much less being the head of one of the industry’s key charities for 25 years. He still loved movies, though. Growing up in Pasadena, California, he would go to Academy Cinemas—still open—where he’s “pretty sure” the first movie he saw in a theater was 1974’s disaster film Earthquake. Three years later, 11-year-old Vradenburg and his mother saw the first Star Wars at Los Angeles’s iconic Cinerama Dome; judging by the Darth Vader and Stormtrooper helmets that sit atop his desk, it was an impactful experience.

Yet, going into college Vradenburg intended to be a financial planner. In his senior year, he was assigned to write a paper based on interviews with people in his chosen field, which ended up convincing him he belonged on a different path. “It’s probably just coincidental,” says Vradenburg, but “the people I interviewed just weren’t of high moral fiber.”

As a child, Vradenburg had reaped the benefits of the Boys and Girls Club of Pasadena, the local parks and recreation department, and the YMCA system. “There were always people trying to help,” he says. “That’s what I remember. When I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, I said, you know what? I’ll go work for a charity. This will be my way of giving back, and then I’ll figure out what’s next.”

Between 1991 and 1995, he worked for two charities—the American Heart Association and the National MS Society—before tackling the “what’s next.” But he still didn’t know what that would be. He worked for eight months at LEGO Group as a promotions specialist before a friend connected him with Professional Sports Publications (PSP), a sports media company, where he stayed for a little over two years.

“When I was at PSP, the phone rang, and it was a board member from the MS Society. And that man was named Tom Sherak.” The long-time studio executive and industry icon—and future president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—recruited Vradenburg to join Will Rogers as their executive director, which he did in 1997. “That’s how I ended up at Will Rogers. How I stayed there for 25 years would take a lot more time [to explain],” he says. “Let’s just say there was always something new to work on. The industry’s great. The people are great. There was just no desire to go and look anywhere else.”

From Will Rogers’s points of view, explains Vradenburg, the board just wanted someone who knew about nonprofits. “Charities don’t get to be 85, almost 90 years old, without some peaks and valleys. It was in a valley at that point in time,” he says. The ’90s marked a turning point for the charity, which had recently moved from New York City to Los Angeles, following the general migration of movie folk that was happening around that time. Consolidation was in full swing, with family-owned circuits being gobbled up by corporate entities. “There was just this disconnect” between Will Rogers and the new exhibition-industry figures entering the business, says Vradenburg. “They hadn’t grown up in the industry. They didn’t have summer jobs in the industry. They were new to it”—and they didn’t really get why they were expected to support Will Rogers.

“Now, I did not rebuild these bridges and create this community,” says Vradenburg. That was up to the industry veterans on the board, who shored up relationships while Vradenburg came up with plans to raise money, made sure that Will Rogers was on the right side of government regulations, and just generally kept things running. Those same board members—including Sherak, Wayne Llewellyn, Eric Clovis, Chuck Viane, Salah Hassanein, Dan Feldman, and Jerry Forman—mentored Vradenburg as he got accustomed to the inner workings of the exhibition industry. After six months, he hired a second person; a year later, a third, Timiney Mayhew, still Will Rogers’s operations manager.

By the time Covid rolled around, the Will Rogers staff was a whopping six people—who, with the help of bankers, payment-processing companies, social workers, exhibitors, and more, carried out the daunting task of raising and distributing money to cinema industry workers who had been furloughed or laid off. Will Rogers went from helping 300 to 600 people per year—the pre-Covid average—to 10,000 in 2020.

“There was about a three- to four-month period where workers, especially workers from exhibition, were in no-man’s-land. They were nowhere,” says Vradenburg. Federal relief programs hadn’t yet kicked in, and even after they did, there were thousands of cinema workers who weren’t eligible because they were still on the payroll, albeit at half salary. “We were challenged to help these people. And we pulled it off. Every day was just—our hair was on fire.” It was only after the second stimulus went out and the cinema industry began to show signs of rumbling back to life that he could take a deep breath. “But man, was it worth it. That’s my proudest moment, without a doubt.”

Before Covid, Vradenburg’s proudest achievement at Will Rogers was the 2002 merger of the Will Rogers Memorial Fund with fellow industry charity Foundation of Motion Picture Pioneers to form the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation. “Mergers are not easy,” Vradenburg says, “even if both parties are willing to do it. You’ve got to work through two sets of bylaws, two sets of boards, two corporate charters. The state attorney general needs to sign off. And you have to work out a whole new culture. We were able to do that, because we thought it would be best for both charities to be one, as opposed to being two separate entities.”

Twenty-five years is a good chunk of time in which to rack up some major accomplishments. In addition to overseeing the merger and the cutting of thousands of Covid relief checks, Vradenburg was instrumental in the 2015 creation of Brave Beginnings. An offshoot of the Will Rogers Institute, which is concerned with health education and research, Brave Beginnings gives grants to U.S. hospitals so they can buy life-saving neonatal equipment for premature babies; they’ve given $9.5 million to over 200 hospitals so far.

Still, Vradenburg leaves Will Rogers wishing he’d done more to overcome what he deems the institute’s biggest challenge: “Communication throughout the industry. Helping people understand that this charity exists, what its history is, that it’s here to help people. Because even after Covid, we still have workers in the industry who don’t know about Will Rogers and don’t realize that Will Rogers is there for them.” Now, that job is in the hands of Christina Blumer, who was its director of development and director of operations before succeeding Vradenburg as its executive director earlier this year.

Vradenburg left the role of executive director at Will Rogers—though he still serves on its board—after a quarter century, having helped bring 10,000 people through the biggest period of chaos the cinema industry has ever faced. It’s a high note to leave on, so much so that the timing almost seems intentional. Actually, the call that would lead to his current role came out of the blue.

Vradenburg’s career transition came when Jerry Forman—one of Vradenburg’s early industry mentors, former president of Pacific Theatres and NATO chairman, current NATO of California/Nevada chair emeritus—called him up to tell him that NATO of California/Nevada’s long-time president and CEO Morton Moritz was retiring. Would he be interested in interviewing? Though Vradenburg had no plans at that point to leave Will Rogers—he estimates he hadn’t updated his resume in “about 10 years”—something about the new opportunity intrigued him. “I’ve always prided myself on being a good administrator and running a tight ship. This gives me an opportunity to do [that], do more of the business operations, and not have to focus so much on fundraising,” he says. “I know this industry. I know these people. I’m not going to something completely foreign.”

These first few months have been all about surmounting the learning curve, something that he says is “happening daily, almost hourly.” “I knew about exhibition. But my weakness is, I’ve never worked for a theater. So I don’t understand the inner workings of how the theater business works. And I still don’t. And I’m learning that.” But, at its core, leadership positions at Will Rogers and NATO of California/Nevada share two key priorities: communication and advocacy.

“When you work at a charity, you’re working for something much bigger than yourself. What you’re doing makes a huge difference to people on a personal and individual level,” he says. At NATO of California/Nevada, the scope of that work has expanded. Now, he advocates for an industry, figuring out strategies to remind the public of the fun of moviegoing, while convincing lawmakers that theaters are still facing myriad issues—labor shortages and supply chain delays among them—and need their help. “You’re talking about an industry that was shut down for two years,” he says. “No income. Yes, there was a grant program, and that helped. But that helped keep them in business. It did not put them back on their feet. It is not as glitz as you might think it is because you saw something on your weekend news about how great the box office was this weekend.” Recently, lobbying from NATO of California/Nevada allowed cinemas access to the California Venues Grant Program, which was not open to them in 2021. “That was a priority for us,” Vradenburg says. “It’s not a big grant program. It’s not going to pay out big sums of money like SVOG [the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant] did on the national level. But it will help, especially our smaller operators, just get by.”

Meanwhile, no longer being the head of Will Rogers doesn’t mean stepping away from charitable giving entirely; in August, NATO of California/Nevada issued its 2022 Community Grants, giving $427,500 to charities across California and Nevada. It’s something that’s important to NATO of California/Nevada as well as Vradenburg himself: “We still really believe in investing in the communities where our theaters are and where the employees are located. Because we know some employees will need those services, unfortunately, here and there. It’s always been important to [NATO of California/Nevada], and it continues to be so. It’s a cultural value in this organization.”

Share this post