U.S. wealth inequality has risen for decades, especially since the 1980s, and recently hit its highest levels since 1928. The top 20 richest Americans now own as much wealth as the bottom half of all Americans. No wonder we keep hearing rhetoric from politicians and economists, from Bernie Sanders to Hillary Clinton to Thomas Piketty, about how “the rich are getting richer.”

Has the same proven true of the box office? Are the highest-grossing movies taking up a larger slice of the pie in recent years and decades? Or has the American box office been resistant to these trends that have permeated the rest of the American economy?

In an attempt to answer these questions, I collected and analyzed yearly box office data for the top 100 films each from 1980 through 2015. The results are two-pronged.

The first prong shows that, unlike the American economy at large, from 1980 to the present the top films have actually made up an incrementally smaller percentage of cumulative film-industry gross. And yet the second finding is that 2015 reversed that trend sharply, with the top films making up the highest percentage of total grosses in many years. Depending on how one evaluates the data, 2015 represents perhaps the greatest “box office inequality” since the early 1990s.

Was this a one-time exception, or did 2015 indicate a new paradigm in which the biggest movies will make up an ever-increasing percentage of total box office revenue? Is this a positive or negative development? And what does it mean for the movie business?

Greater box office equality amid greater economic inequality

Using the top 100 highest-grossing films of each year, I calculated how much of that total was earned by the top film, then by the top five films, then by the top 10, top 15, top 20, and so on. I find that, unlike the American economy at large, from 1980 to the present, the top films on average actually made a smaller percentage of the top 100 films’ total gross.

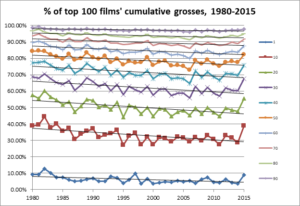

In the graph below, the blue line at the bottom represents the top film and charts its earnings as a percentage of the top 100 films’ total earnings. The red line above it shows that percentage for the top 10 films, the green line above that shows the percentage for the top 20 films, and so on. The trend line over the last 35 years is uniformly down at all levels. Perhaps not dramatically, but the trend is visually noticeable and appears through every segment of the data.

For example, in the early 1980s the top film consistently averaged around 9 percent or so of the top 100 films’ total gross. By the 2000s and 2010s, the year’s box office champ was usually down to around 3 percent to 4 percent.

Similarly, in the early 1980s, the top 10 films usually earned around 40 percent of the top 100 films’ total. By the 2000s and 2010s, that had generally declined to around 30 percent.

In that respect, the box office mirrored other elements of the entertainment industry in proving resistant to the broader trends enveloping the American economy, in which the richest took home an ever-increasing portion of the pie. Similarly, the top 100 concert tours currently now take in about 44 percent—and declining—of all concert revenue, a precipitous drop from making nearly 90 percent of revenue as recently as 2000. (Don’t cry too hard for the pop stars: the top 1 percent of music acts still made 77 percent of overall music revenue in 2013.)

But it’s worth noting when that trend toward economic equality occurred for the movie industry: almost entirely during the 1980s and 1990s. In fact, throughout the 2000s and 2010s all these numbers remained essentially flat.

For the music industry, most of their economic equalizing has occurred since 2000 as a result of technological developments, notably iTunes and the iPod. As NYU music instructor Braxton Boren writes, “The shift from album-bundling to track-by-track purchases has been bad for overall revenues, but especially for the ‘1 percent’ of music acts: In the album days, consumer spend was monopolized by a handful of $20 ‘must have’ records released by the Beatles and Michael Jacksons of the world. Today, that same spend (or what’s left of it) can be spread across dozens of artists—with each one compensated only for the specific tracks a consumer picks.”

A similar technological development likely contributed to the economic equalizing of the film industry in the 1980s and 1990s, but stalled that trend in the 21st century: VCRs. The machines went from near-zero market penetration in 1980 to 50 percent by 1988, then to 70 percent by 1990 and 80 percent by 1994. As a result, the biggest blockbuster movies—though still huge—were less preeminent on the pop-cultural landscape.

To be fair, there were other factors too. Looking at the list of the highest-grossing film by year, the mid and late ‘80s stand out as a period when the highest-grossing movies often weren’t particularly enhanced by the big screen—they weren’t the superhero films or special effects–laden blockbusters of the kind that had long packed audiences into cinemas. Examples: Beverly Hills Cop led in 1984, Three Men and a Baby in 1987, and Rain Man in 1988.

Regardless of the contributing causes, by the mid-2010s the trend had become fairly predictable: the top X number of films always made about Y percent of the total, year after year after year. Until 2015.

The year everything changed

The top American baseball slugger had always hit about 40 home runs per season for decades until Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa both topped 60 in the same year. In the same way, 2015 shattered all the longest-held records for box office inequality. “But wait!” one might counter. “Isn’t that just because Star Wars: The Force Awakens smashed all box office records?” The casual observer might jump to that conclusion, but the answer is actually, no.

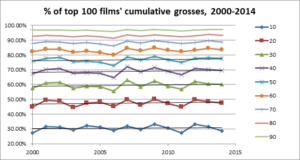

By our numbers, the number 2 through 20 highest-grossing films last year cumulatively made 46.55 percent of the year’s top 100 total revenue—the highest such number since 1992, at 46.49 percent. In other words, it wasn’t just The Force Awakens skewing figures at the top spot. It was also other huge smashes in the runner-up positions, including Jurassic World, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Inside Out, and The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2.

By comparison, the biggest box office hit before The Force Awakens to utterly command a particular year was Titanic in 1997. The Force Awakens, with 9.07 percent of the year’s top 100 total revenue, is the high-water mark since Titanic made 9.83 percent. As might be expected, Titanic comprised much more of the top 100’s total in its year than the 1996 leader Independence Day had the year before. But compared to the year before, the top 20, top 30, and top 40 films in 1997 actually earned a lower percentage of that total year-over-year.

Put another way, while Titanic provided a huge upward pull, the rest of the year’s top echelon at the box office didn’t perform well enough to make it a banner year overall. 1997 wasn’t a year for the record books; one particular 1997 movie was.

Contrast that with 2015. Last year posted the highest share of top 100 earnings going to the top 10, top 20, and top 30 films since 1984, 1983, and 1989 respectively. It also had the lowest share going to the bottom 10 and bottom 20 films (aka titles 91 to 100 and 81 to 100) since 1992 and 1989, respectively. As if this weren’t enough, it also had the lowest share going to the middle 10 films (titles ranked no. 46 to 55) since 1989.

In 2015, for once, the box office was actually acting like the American economy: the “lower class” was doing terribly, the “middle class” was doing terribly, but the “upper class” was doing better than ever.

| 2015 category | % earned of top 100 | Highest/lowest since … | % earned of top 100 |

| Top 10 films | 38.80% | 1984 | 40.04% |

| Top 20 films | 55.62% | 1983 | 56.45% |

| Top 30 films | 67.63% | 1989 | 68.01% |

| Nos. 2–20 films | 46.55% | 1992 | 46.49% |

| Bottom 10 films | 2.32% | 1992 | 2.29% |

| Bottom 20 films | 5.11% | 1989 | 4.50% |

| Middle 10 films | 5.12% | 1989 | 4.85% |

Another important factor here might be the quality of the films themselves. While at least a few films each year truly permeate the mass culture and approach a “must see” status among audiences, 2015 saw a number of releases that were widely considered mainstays of the cultural conversation—in some cases titles ranking as far down as the top 20 or top 30 of the yearly box office, instead of just the top five or top 10 as in most other years. This in turn may have significantly contributed to overall “box office inequality,” as films ranking in the number 10 to 20 range or 20 to 30 range of the yearly box office still packed audiences into the theaters as had rarely occurred before. To name a few such titles: The Martian, The Revenant, Fifty Shades of Grey, Trainwreck, Straight Outta Compton, and Mad Max: Fury Road.

The last year in which the top 30 made up such a large share of the top 100’s earnings was 1989. Just as always, that year had a few “must see” films in the top 10 by box office, including Batman, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and Back to the Future Part II. But it also had high-grossing films throughout the top 30, many of which are now considered classics: Dead Poets Society, When Harry Met Sally, The Little Mermaid, Born on the Fourth of July, Field of Dreams.

What Hollywood can learn

Was 2015 an exception, or the start of a new trend of box office inequality? For now it appears to have been an exception.

As of this writing in mid-September, the start of the 2016 fall movie season, the box office breakdown has returned more or less to 21st-century form. Although there are three months left in the year, that final stretch would have to be highly unequal in order to skew the entire year in that direction. And no film—not even two of the most anticipated releases, Rogue One and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them—is expected to earn a sum on the level of a Titanic or Force Awakens, meaning that when all is said and done, 2016 will likely mark a return to normal.

Income inequality can result in such deleterious effects as unequal representation in campaign finance and government lobbying, a weakening of shared commonalities and cohesiveness among the country’s populace, and a lower class often unable to afford such basics as health insurance. Box office inequality has few such consequences. Movies aren’t human beings. With that in mind, was 2015’s modern-record box office inequality a positive or negative development?

On the one hand, it’s bad for smaller or independent filmmakers and studios, who often produce what are considered to be higher-quality or more highly acclaimed films. The average American moviegoer attends about four times a year. If that hypothetical audience member is spending those four tickets on three or four blockbusters instead of one blockbuster, two mid-budget films, and an indie, that’s clearly bad for anybody aspiring to work outside the tentpoles.

On the other hand, the reason for such box office inequality last year was arguably the plethora of excellent movies that people wanted to see. If that’s why the top 30 movies represent such a large percentage of the top 100’s earnings, then greater inequality may be a byproduct of what was largely a positive development. Indeed, overall ticket sales increased year-over-year in 2015, following ticket-sale declines in four of the previous five years.

Perhaps it is worth having the pie apportioned slightly less fairly if the pie itself gets larger.

Share this post